World Models

World models are still a central topic in RL, even after 30 years since their inception. But they're also growing in popularity, even outside of RL. Nowadays interest is fueled by video models like OpenAI's Sora, Luma's DreamMachine, Google's Veo, or Runway's Gen-3-Alpha. The idea here is that to be able to generate accurate physics, occlusions, deformations, or interactions, you need to have proper knowledge of how the real world works. This post will trace the development of world models from the last ten or so years up to today, focusing on key ideas and developments.

A world model is a very specific thing. It's a mapping \((s_t, a_t) \mapsto s_{t+1}\) from state-action pairs to subsequent states and represents causal knowledge of the world, in the sense that taking an action \(a_t\) might lead to \(s_{t+1}\) but taking a different action \(a_t'\) might lead to a different \(s_{t+1}'\). Thus, world models are inherently counterfactual. Video generation does not necessarily indicate world knowledge because the space of possible realistic videos corresponding to the prompt is very large and a video generation model needs to successfully sample only one of these videos.

Often a world model also requires learning the reward dynamics \((s_t, a_t) \mapsto r_{t}\) and even the observations \((s_t) \mapsto o_{t}\) in the case of partial observability. A dominant approach back in the day was to have a RNN processing sequences of observations and then an autoencoder that takes in the RNN's hidden state and produces a kind of latent \(z_t\) which represents the state.

Learning a world model offers multiple benefits. In particular:

- It enables planning, which is guaranteed to minimize some cost function at test time. Without planning you can only hope that what was learned at train time will be useful at test time.

- It is more sample-efficient compared to model-free methods, because learning state transitions provides many more bits of useful signal when training compared to scalar rewards.

- It forms abstract representations, as typically the dynamics predictor takes in latent representations, not raw observations.

- It allows for transfer and generalization across tasks and domains.

When it comes to planning, there are different ways to do it. For discrete action spaces MCTS is common (but we'll discuss it in another post). For continuous ones, MPC and Dyna are common:

- Model predictive control (MPC) essentially plans a trajectory, executes a single step from it, and then replans again. It is sample-efficient and well-understood. It's also adaptive (because of the closed loop planning) but costly to execute because you replan at every step. It is also myopic since you do not commit to executing the full planned trajectory but only its first step. The actual planning of the trajectory typically involves the cross-entropy method (CEM).

- Dyna is similar but allows for deep exploration where the agent commits to executing its learned policy. Essentially, you fully-train a policy within your world model, which acts as a simulator, and then you deploy that policy in the real environment, letting it collect new data. This data is added to the replay buffer from which you will retrain a policy and repeat the process as necessary.

The idea of learning from imagined experiences has been around at least since the '90s [1, 2] but getting these things to work on bigger, more realistic problems has been slow. In 2015 it was shown that action-conditioned frame generation can be learned in the context of Atari games [3]. The architecture used a CNN feature extractor, a LSTM module whose output hidden state gets concatenated with the encoded actions, and a decoder CNN to produce images. Even without actual control, it showed that the \((s_t, a_t) \mapsto s_{t+1}\) mapping can be scaled up adequately. In 2018, a major paper came out - Schmidhuber's "World models" [4]. In it, a VAE extracts a low-dimensional representation of the visual observation, \(z_t\), which is then passed to a RNN that predicts the future \(z_{t+1}\), conditional on past actions. The hidden state along with \(z_t\) is passed to a small controller which selects actions. The decoder part of the VAE reconstructs the imagined frames. Then, training in the world model gives you pretty good performance in the actual environment.

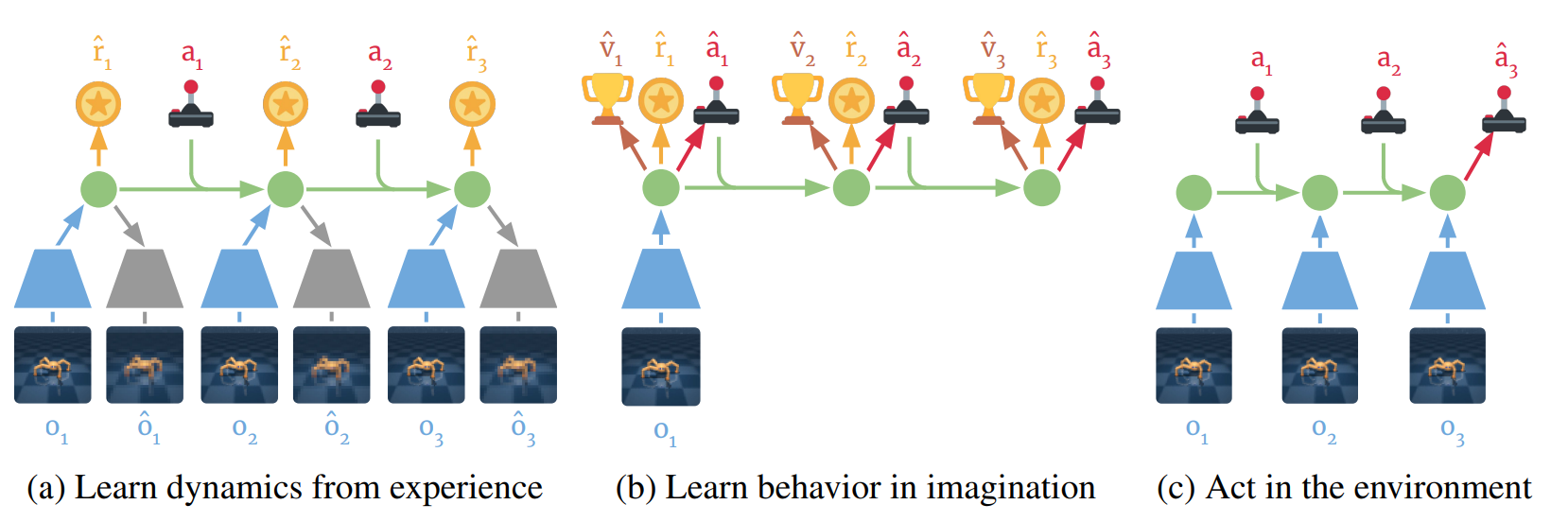

In 2019 Hafner introduced the recurrent state-space model [5] (RSSM), where the transitions are decomposed into both deterministic and stochastic components, offering improved and stable learning. It used MPC for planning. This work was then adapted into Dreamer [6] which uses Dyna-style planning and is truly a big achievement in world model research. Dreamer learns the dynamics from sequences of executed roll-outs and the policy from interactions in the imagined world dynamics. The gradients with respect to the policy weights actually go through the whole imagined trajectory. Subsequently, DreamerV2 [7] was introduced to plan with discrete world models, and then DreamerV3 [4], which could mine diamonds in Minecraft without human data or curricula. In "Daydreamer" [9] they applied Dreamer on a real world quadruped robot, which learned how to stand up and walk straight just within an hour of real-time interaction.

All of these methods learn a world model that is specific to the current environment and then act (optimally) in that same environment. A recent trend has been to focus instead on generalization and transfer. That is, can the world model capture patterns which are common across multiple environments thereby helping the agent to transfer policies to newer settings?

In that setting "Visual foresight" [10] was one of the first methods. At train time a number of robots collect experience in an autonomous unsupervised manner and a video prediction model is trained. At test time novel manipulation tasks, based on novel reward functions, are solved using MPC. A similar method is "Plan2Explore" [11]. Here we first train a world model without having any task-specific rewards, which is called the exploration phase, and then finally enable the task rewards, at which point the agent very quickly learns to solve the task, due to the world model being already trained. For the exploration phase, a policy that maximizes next state novelty is trained within simulated trajectories. The authors measure epistemic uncertainty as the information gain of the next frame hidden values.

LEXA [12] is an interesting model where we use the world model to train two agents - one explorer which is trained on imagined rollouts and maximizes some exploration objective, and one achiever which is trained to learn policies that achieve, or reach a given target state. As you can see the idea is relatively similar to the papers before. And one can imagine that adding language, as a universal interface for describing tasks and goals, can allow for the zero-shot solving of novel tasks from text at test time. This is what was done recently [13]. Researchers took DreamerV3 and generalized it to take in per-frame text tokens and to be able to decode the latent state into images and text.

Since 2021 two trends have started to pick up stream, offline RL and foundation models:

- Offline RL is the approach of learning policies from fixed, previously collected datasets. Thus, there is no environment interaction involved, which poses difficulties to finding good policies.

- Foundation models are large-scale models, trained on huge amounts of diverse data, with the intent of capturing as much generalizable knowledge about the world as possible. The emphasis here is on scale.

Naturally then, offline model-based RL is about training a massive world model on massive internet-scale offline datasets, without interacting with any environments. Then, the world model is used to plan action sequences that can easily generalize to novel environments and tasks.

In general, to learn a good world model from offline data one needs to balance the potential gain in performance by escaping the behavioural distribution and finding a better policy, and the risk of overfitting to the errors of the dynamics at regions far away from the behavioural distribution. In MOPO [14] they address this by subtracting some quantity proportional to the model uncertainty from each reward, thereby obtaining a new, more conservative MDP, on which to train the policy. In [15] they show that adding noise to the dynamics of the world model helps generalization, allowing better performance with new dynamics at test time.

And finally, the latest development in world models is to utilize generative models. For example, diffusion models can serve as game engines. You play DOOM and the world model generates the next game frame, in real time, based on past and current frames and actions [17]. So you're in effect playing DOOM within your neural network. Another similar idea is digital twins. Say you train a generative world model on top of all the sensors in a large-scale industrial factory. And then you add a language interface for good measure. Then you'll be able to make queries like "Tell me, factory, were there any unusual events last night?".

The first big generative world model was Wayve's GAIA-1 [18], for driving. It has about 7B parameters. It works by taking in multiple modalities, like image sequences, IMU values, and text explanations, tokenizes them using separate encoders and feeds all resulting tokens to a LLM-like autoregressive predictor. The predicted tokens are decoded back to video using diffusion. The end result is a model that can generate future imagined photorealistic image sequences, all conditional on actions, text, and past images. This is very useful, as it allows simulating different driving conditions and rare events.

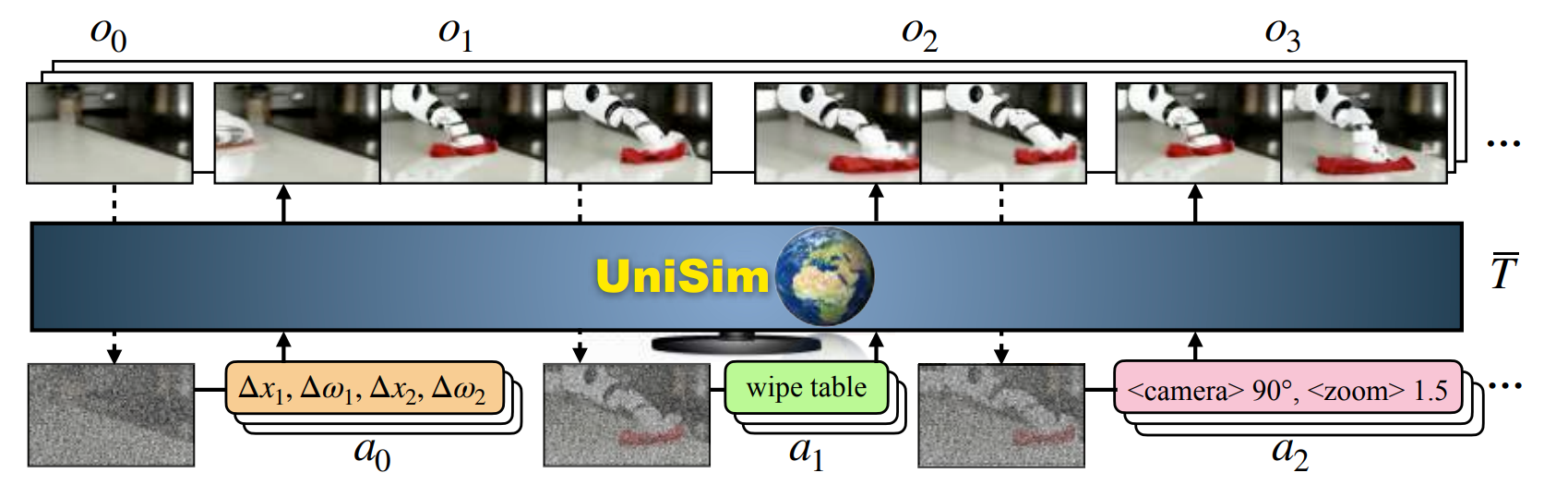

Another example here is UniSim [19] which tries to learn a universal simulator of real-world interaction through generative modeling. It is a video diffusion model (applies diffusion over pixels) that predicts the next observation frames from noisy previous frames and actions. And actions can be supplemented with language so that the model can also plan using language.

The latest big advancement is Genie [20]. This is a generator for interactive environments. The user can requests a "futuristic, sci-fi, pixelated, platformer" and Genie will create a fully-playable environment styled according to that request. The model is trained from video-only data and has the following components:

- A video tokenizer, based on a VQ-VAE [21], takes in video frames \(\mathbf{x}_{1:T}\) of shape \((T, H, W, C)\) and outputs tokens \(\mathbf{z}_{1:T}\) of shape \((T, D)\).

- A latent action model (LAM) infers latent actions from frame sequences in an unsupervised manner. It works as follows. First, from a frame sequence \(\mathbf{x}_{1:t+1}\) we estimate latent actions \(\tilde{\mathbf{a}}_{1:t}\). Then, from \(\mathbf{x}_{1:t}\) and \(\tilde{\mathbf{a}}_{1:t}\) we predict \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}_{t+1}\). Using another VQ-VAE-style loss, we can force each of the \(\tilde{\mathbf{a}}_{1:t}\) to be one of a small number of action tokens, e.g. \(8\). These end up perfectly corresponding to standard platformer actions (left, right, up, down, etc.).

- A dynamics model which takes in past tokens \(\mathbf{z}_{1:t-1}\) and detached latent actions \(\text{sg}[\tilde{\mathbf{a}}_{1:t-1}]\) and outputs the next tokens \(\hat{z}_t\). A special MaskGIT transformer [22] is used, one that separates attention over time and space into separate layers in each block.

Thus, the current trend of scaling world models to billions of parameters and to internet-size training data from all kinds of scenarios, seems to be very promising. Naturally, there are still a lot of challenges and the community has not converged on what are the best practices for this approach. But it is believed that there's a lot of room for improvement. Scaling laws apply, and most of these models are still not practically usable to yield real value. The most exciting time will be tomorrow. The second most exciting time is today.

References

[1] Schmidhuber, Jürgen. Making the world differentiable: on using self supervised fully recurrent neural networks for dynamic reinforcement learning and planning in non-stationary environments. Vol. 126. Inst. für Informatik, 1990.

[2] Sutton, Richard S. Dyna, an integrated architecture for learning, planning, and reacting. ACM Sigart Bulletin 2.4 (1991): 160-163.

[3] Oh, Junhyuk, et al. Action-conditional video prediction using deep networks in atari games. Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015).

[4] Ha, David, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. World models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.10122 (2018).

[5] Hafner, Danijar, et al. Learning latent dynamics for planning from pixels. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019.

[6] Hafner, Danijar, et al. Dream to control: Learning behaviors by latent imagination. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.01603 (2019).

[7] Hafner, Danijar, et al. Mastering atari with discrete world models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02193 (2020).

[8] Hafner, Danijar, et al. Mastering diverse domains through world models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04104 (2023).

[9] Wu, Philipp, et al. Daydreamer: World models for physical robot learning. Conference on robot learning. PMLR, 2023.

[10] Ebert, Frederik, et al. Visual foresight: Model-based deep reinforcement learning for vision-based robotic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.00568 (2018).

[11] Sekar, Ramanan, et al. Planning to explore via self-supervised world models. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020.

[12] Mendonca, Russell, et al. Discovering and achieving goals via world models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021): 24379-24391.

[13] Lin, Jessy, et al. Learning to model the world with language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01399 (2023).

[14] Yu, Tianhe, et al. Mopo: Model-based offline policy optimization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 14129-14142.

[15] Ball, Philip J., et al. Augmented world models facilitate zero-shot dynamics generalization from a single offline environment. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021.

[16] Lu, Cong, et al. Challenges and opportunities in offline reinforcement learning from visual observations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.04779 (2022).

[17] Valevski, Dani, et al. Diffusion Models Are Real-Time Game Engines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.14837 (2024).

[18] Hu, Anthony, et al. Gaia-1: A generative world model for autonomous driving. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.17080 (2023).

[19] Yang, Mengjiao, et al. Learning interactive real-world simulators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06114 (2023).

[20] Bruce, Jake, et al. Genie: Generative interactive environments. Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning. 2024.

[21] Van Den Oord, Aaron, and Oriol Vinyals. Neural discrete representation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

[22] Chang, Huiwen, et al. Maskgit: Masked generative image transformer. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022.