Visual Perception

Visual perception is the complex process of transforming the light entering the eye into meaningful mental representations of the surrounding environment. In humans the intricate mechanisms behind our visual perception are responsible for helping us recognize objects. Suppose we take the actual object recognition to be simply the assignment of a previous known semantic label to the visual pattens present in our field of view. Then it would seem that recognition is a deterministic process? Yet, clever illusion can actually show how the same shape can be recognized in different ways depending on the context. Consider the simple Neckar cube which can snap its orientation or the complicated pareidolia effect where people see faces in the clouds. Insofar as our perceptual awareness may be tricked into recognizing different semantics from the same input it becomes evident that perception is a deep topic tied to the nature of the human cognition.

Historically, vision theories have been gravitating around three main views:

- Indirect or constructivist theories, championed by Hermann von Helmholtz, state that the visual stimuli that reach our eyes are quite sparse and therefore our brain needs to construct hypotheses and make inferences about what the eyes see. To an extent, this sparsity of information should be evident. To find out the colour of an object we need both the colour of the reflected light reaching the eye, and the colour of the light shining on the object. Yet, we only have access to the final reflected colour. Hence, an ill-posed problem. From here, one can make various arguments about how mechanisms promoting colour, depth, and shape constancy are utilized. Overall, in this view, meaning is added to, rather than contained in the stimulus.

- Direct theories, advocated by James Gibson, argue that the visual stimulus is actually quite rich and you don't need to make any inferences or guesses. Textured surfaces create gradients of disparity in the retina. Our movement creates a constant flow of motion gradients. We perceive to act and act to perceive in a continuous loop. Moreover, there are many invariants from which we can pick-up information - the relative object sizes stay the same as the viewing distance changes, the relative amounts of light on objects stay the same as the overall light intensity changes and so on.

- Computational theories, led by the influential David Marr, state that perception is an information processing task. To understand perception one needs to understand at a high-level, what are the inputs and outputs, and the goal of the system, at a mid-level - the algorithm that solves the problem, and at a low-level how is the algorithm implemented in the neuron or transistor substrate. And the ultimate goal is to recognize and localize objects and then assign meaning to them.

Lightness and Colour

When talking about light, the quantities of interest can get a little confusing. Radiometry measures actual radiation and light energy in terms of absolute power. Common units of measurement are joules and watts. Here the total energy in the visible spectrum is just the integral of the energy across all visible wavelengths. Photometry instead measures how the light is perceived by the human eye. Here we talk about luminance and the units of measurement are lumen, candela, and lux. The total luminance of an object is calculated by integrating the radiant power across the wavelength, weighed by a luminosity function. This luminosity function is standardized and gives the sensitivity of the eye to that wavelength. There are actually two such functions - one for well-lit conditions (photopic) and one for poorly-lit ones (scotopic). The human eye is maximally sensitive to green light.

Material surfaces reclect light. The bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) can model this reflectance. It is defined as

where \(i\) is an incident light ray, parameterized by an azimuth \(\phi_i\) and zenith angle \(\theta_i\), \(r\) is the reflected light ray, parameterized using \(\phi_r\) and \(\theta_r\), \(\omega_i\) is the angle between \(i\) and the surface normal \(\textbf{n}\) at that point, and \(\omega_r\) is the angle between the surface normal and the reflected ray. \(L_r(\omega_r)\) is the radiance, or power per unit surface area per unit solid-angle in the direction \(r\) and \(E_i(\omega_i)\) is the irradiance, or power per unit surface area due to incoming light ray \(i\). Thus, the BRDF measures reflectance as the ratio between reflected power in a given direction and total power received by a surface. The differentials ensure that only irradiance caused by a infinitesimally small cone in the direction of \(i\) affects the radiance in \(r\).

Suppose we fix the two directions and the reflectance of a colour pigment is 0.25. Then if the incoming intensity is 1000, the output intensity will be 250. Suppose we now turn down the lights and the new incoming intensity is 500, and the new output intensity becomes 125. Clearly, less energy reaches the observer now and the object would appear darker. Yet, the lightness, which is a measure of how we perceive luminance with respect to a standard observer, stays the same. This phenomenon is called lightness constancy.

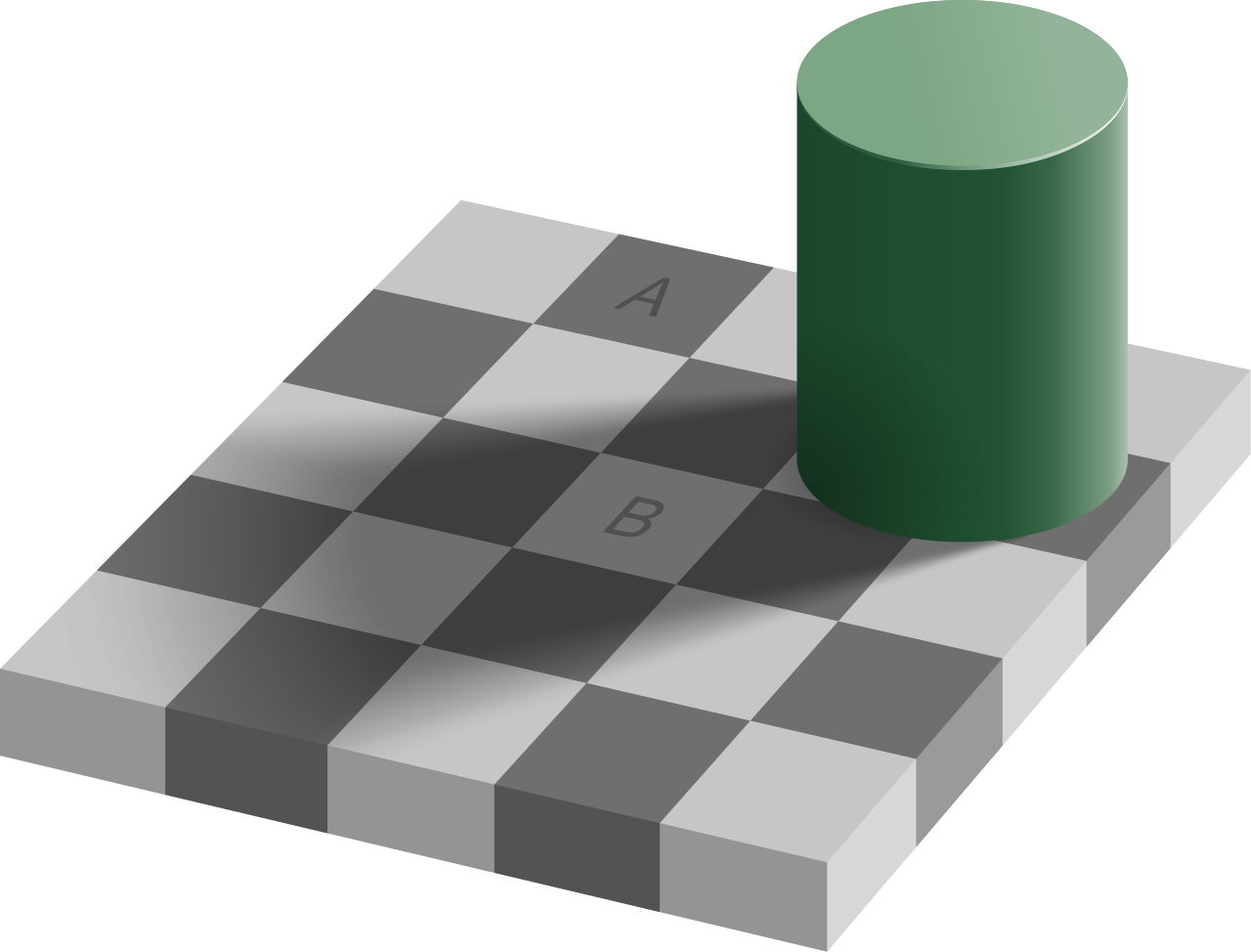

Turns out that the brain perceives lightness by looking at neighboring patches of pixels and comparing their relative luminance. Thus, if all objects in the scene change their illumination by the same amount, or if the brain assumes that this is the case, the lightness will not change. Thus, lightness with respect to different illuminations is an invariant.

When it comes to colour vision, we are interested in how a surface reflects one particular wavelength, not the average wavelength. Animals have evolved specialized colour receptors with different spectral sensitivities - usually two in dichromats, or three in trichromats like humans and some monkeys. Here the important invariant is that the ratio of short, medium, and long wavelength light remains constant as the overall illumination changes. If we shine a red light uniformly on all objects of the scene, all objects will appear reddish, but in fact the relative amount of short, medium, and long wavelength light will remain the same. Like before, spatial comparisons are needed in order to assess the underlying object reflectance.

It takes two photoreceptors with different spectral sensitivity for colour vision. This is because one receptor can increase its response either because the wavelength has changed, or because the energy quantity has increased. Thus, a single photoreceptor type confounds these two, which is not the case with two or more. So why then do we have three? Most probably to reduce the number of possible metamers.

Consider two photoreceptors - one sensitive to long wavelengths (L) and one to medium (M) such that their sensitivities overlap. If we trigger them using monochromatic light of a single wavelength we can record their activations. However, since spectral sensitivities are bell-shaped, for each one of them there are two different wavelengths that can produce the same excitation level. Therefore, there exist combinations of light that will produce the same joint effect on the photoreceptors as the monochromatic light would. This creates ambiguity as the photoreceptors cannot distinguish the combined light from the monochromatic one. These ambiguous light combinations are called metamers. Having three different photoreceptor types reduces the number of such metamers.

Motion Perception

Motion detection is an important feat of our visual system. Moving objects cause temporally-correlated activations in neighboring photoreceptors in the retina and the goal is to detect this temporal correlation. One model for a simple motion detector is given by Reichardt-Hassenstein where two neighboring receptors are activated by the light from a moving object, after which each activation is time-delayed using a low-pass filter and cross-processed with the other one. The end result is a small neural circuit which responds only to temporal correlations in the activations along one direction and only tuned for one time-delay. The closer the two neighboring receptors, the more robust they are to uniform light change, but the less capable they are to detection high-velocity movement.

Our motion perception capabilities can be considered both fairly rudimentary and very complex at the same time. It only takes the quick switching of many similar static views of the same object in order to perceive that object as moving. This is how news tickers, progress bars, and all digital video work. Phi movement occurs when these rapidly changing static images induce the perception of a different, in reality non-existing, object which is moving. More complicated motion perceptions are caused by the interaction of various colors, shapes and contrasts and show that it is the complicated activations in our neural circuitry that makes us see motion.

Obtaining 3D Information

Obtaining 3D information from the world is a crucial part for navigating the environment. From a single view, one can rely on the following clues:

- Perspective information due to the projective geometry informs us that an object which is twice as far from us will have half its angular size when projected onto the retina;

- Occlusion, due to the opaqueness of materials, provides a relative ordering of the depths of objects;

- Shape-from-shading, when combined with some basic assumptions like non-specular reflections and light coming always from above, can provide us with accurate estimates of a 3D shape. This is because the reflected light is proportional to the cosine of the angle of the surface and the incident illumination. Hence those areas which are brighter are, roughly, more oriented toward the light source, which provides info also on the convexity of the shape.

3D information from multiple views is even more plentiful.

- In motion parallax, one fixates a given point in the distance and starts moving to the side. Then, points closer than the one which is fixated will move in the opposite direction, inversely-proportional to how close they are to the viewer. Points farther away than the fixated point will move in the same direction as the viewer.

- Optical flow, or the motion vectors originating from our direction of motion, are useful for the maintenance of balance and the perception of self-motion.

- Binocular stereopsis is similar to motion parallax except that it occurs due to the disparities of the projection of the scene onto the two retinas of the eyes. It doesn't provide absolute depth and is only useful for objects which are not terribly far away.

- Eye vergence can produce absolute depth estimates from the angle between the eyes when one is fixated on an object.

Perception and Action

Following David Marr, we can think of our perceptions as serving two functions: one is to recognize objects and the other is to produce actions. The former requires localizing objects and assigning semantics to them. Regarding the latter, there are many low-level actions that directly depend on our perceptions:

- Maintenance of balance is based on the vestibular system in the inner ear and the optical flow from our body sway

- The heading direction, similarly is given by the point at which the optical flow originates

- Time-to-contact can produce an estimate of the time an object will hit us from the rate of dilation of the projection of that object onto the retina. This does not require estimating velocity or distance to the object.