Thoughts After IMOL

I recently attended the Fifth International Workshop on Intrinsically Motivated Open-ended Learning (IMOL 2022) in Tübingen, Germany. It was a very nice event, with interesting presentations and discussions all around. This post aims to summarize the highlights and provide some thoughts on the content discussed therein.

Reinforcement learning is a very interesting area. Unlike supervised or unsupervised learning where we have prediction tasks, here we have control tasks and control is fundamentally tied to consequences. For example, if you are forecasting sales, you cannot in any reasonable way claim that this is a control task, because your forecast will have absolutely no effect on the real sales in the future. Usually, such a forecast is useful to inform us, but it has no real-world consequences and cannot be considered an action.

This is not the case in RL problems, which are about acting in an optimal way. And that is what makes reinforcement learning one of the most important, and in my opinion most exciting, fields in ML right now. It is arguably the closest we have come to a study of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

While intelligence may be the ability to model complicated relationships, what ultimately matters is how you use that intelligence to act - and behaviour can only be observed in a control problem where we are endowed with the notions of time, actions, and states. What makes RL algorithms useful is this particular difference that their quality is evaluated in a behaviour space, rather than a loss space.

Likewise, your goals are ultimately defined in the behaviour space. Minimizing a certain loss or predicting accurately are just means to achieving these goals. Imagine if the reward function of the agent dependended not on the state, but just the action taken - this would correspond to a zombie-like agent that does not take the surroundings into consideration and therefore cannot possibly adapt to the environment.

Like many others, my goal is to assist in creating more advanced and general agents so that we can get insights about us ourselves. Just like a RL agent is trained to solve a task iteratively by interacting with the environment, so do we, humans, improve in understanding ourselves, by building models of ourselves (the RL agents) that we test on simpler environments.

However, when comparing humans and RL agents, it’s hard to abstract away the vast difference in the difficulty of the environments where the two types of agents are tested. In the real world, we judge human-ness by the cohesiveness of the responses to questions and the adequateness of verbal and motoric responses to various prompts for interaction. But in the case of an RL agent, what does human-level performance look like if the testing environment is not complex enough to support these real-world criteria? What does human-like behavior look like in an Atari or MuJoCo game, where we cannot use language as “evidence” of consciousness?

A first step in making RL agents more human-like is to make the rewards endogenous to the agent, as opposed to given exogenously by the environment. With humans, we intrinsically set short-term and long-term goals which guide our behavior in a principled and directed manner. Similarly, we can think of an RL agent as choosing his short-term goals by sampling a reward function. The reward function defines a preference over states and therefore an implicit goal for the agent. This opens up interesting algorithms where the agent can learn to choose his short-term goals by sampling a reward function from a Gaussian process or learning it parametrically. However, what then prevents the agent from always sampling a reward function that always returns high rewards (the equivalent of a goal of doing nothing useful)? With humans this is solved by not being able to choose our long-term preferences over the world. We cannot purposefully reach a mental state of nirvana and stay in it forever. Similarly, if the RL agent is able to choose his short-term goals, there has to be a higher more primal and fundamental meta-reward function guiding him, which the agent cannot engineer.

Another way to make RL agents more human-like is by improving their models of the world (their estimated models for the transition dynamics of the environment). Humans process incredibly large amounts of data each second, but consciously perceive only on a tiny part of it. Similarly, an agent should have a powerful feature extractor that processes all signals from the environment but also subsamples the output considerably (through bottlenecks, attention, pooling, etc.) so that downstream tasks are performed faster and on condensed features only. This mimics the focus in humans and the conscious perception of only a handful of features – those carrying the useful information related to the task. We can then ask what happens if we exogenously add additional features in the environment – those representing another agent, perhaps even itself, and label them “you” or even “me”. Can recognizing the features of an agent exactly like you, and labeling these features “me”, be considered developing an actual identity?

IMOL Highlights

RL is a big and growing research area. Within it we can identify the following possibly overlapping sub-areas:

- Value-based methods - where the agent learns the mean value of states or state-action pairs. The policy is formed by choosing the action with the highest value;

- Policy-based methods - where the agent learns a policy for suggesting the actions directly;

- Model-based methods - where the agent has access to learned predictors for the MDP transition dynamics and can "plan" his actions;

- Offline (batch) RL - where the agent cannot interact with the environment and has to learn entirely from past trajectories;

- Imitation learning - where the agent does not have access to the reward function and has to learn an optimal policy through either mimicking the behaviour of an expert, or learning the reward function;

- Meta-RL - where the agent learns how to learn so that he's able to efficiently few-shot any unseen test tasks;

- Open-ended learning - where the agent learns to extract useful transferable knowledge in the presence of no task.

While there are no hard restrictions on the content, the IMOL conference is concerned primarily with the last one - learning knowledge without having any specific tasks set. This is generally accomplished by the agent setting his own goals and intrinsic motivation - a type of self-generated reward that is independent of the presence of any extrinsic tasks - is key to that regard.

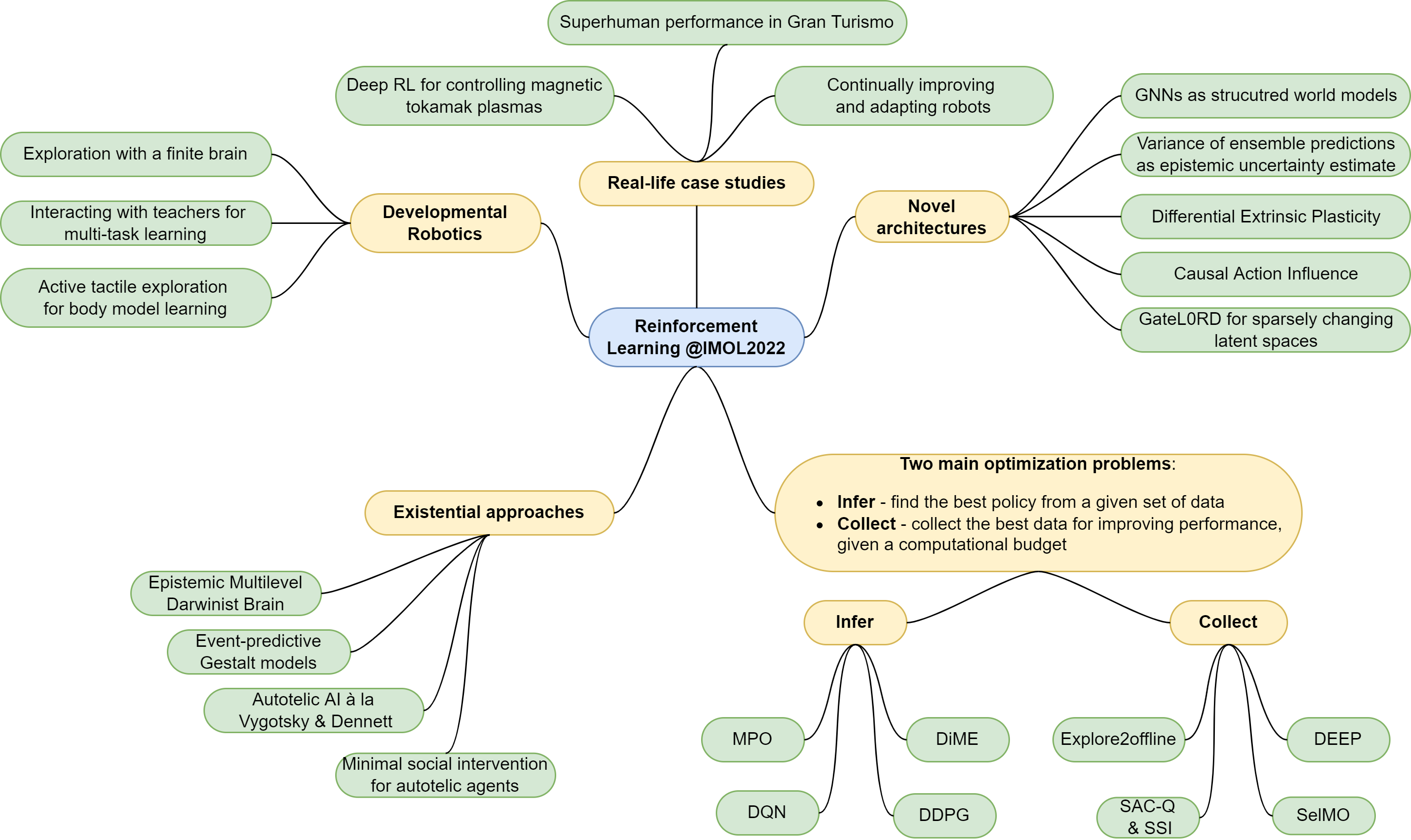

I've summarized the main highlights in Figure 1 below. Note that this is my personal, opinionated selection of the highlights, there were other just as good presentations and topics which I've left out.

In short, I've grouped the presentations into 5 collections.

-

Developmental robotics [1, 2, 3], which aims to study developmental behaviour in embodied intelligence. Just like a toddler explores the state space and tries out different actions, gaining precious knowledge about the world, so is the aim for a robot to explore the state space curiously in the presence of no explicit rewards. The existence of a body which you have to explore and control is a challenge which makes tasks like reaching, grasping, and moving difficult. Note that the actions in such environments are also very low-level - typically the voltage/force/torque applied to a rotor/joint - and the rewards are further down in the

"action \(\rightarrow\) effect \(\rightarrow\) reward" chain. -

Real-life case studies [4, 5], where deep reinforcement learning is applied to practical problems. It is fascinating to see how different academic RL is from real-life RL, and how much more work has to go into the system to make it learn in a real-world scenario. We discussed, among other things, how quantile-regression soft actor critics can be used to achieve superhuman performance in Gran Turismo and how to maximum a posteriori policy optimization (MPO) can be used to train a controller for various voltages in a magnetic tokamak reactor, achieving near-perfect sim2real transfer.

-

Novel architectures [6, 7, 8] - a collection of improvements and ideas that outperform current standards. For example, graph neural networks (GNN) have a powerful inductive bias which is surprisingly useful when it comes to recognizing the structure of the transition model. Another interesting idea was the Differential Extrinsic Plasticity approach - essentially Hebbian learning applied not to the outputs, but the output derivatives of the neurons. Lastly, the GateL0RD approach - a RNN cell with \(L_0\)-regularization applied to the hidden state, convinced me of its utility in modelling e.g. the transition function of the MDP.

-

Infer and Collect [9-16] - DeepMind's idea of treating RL as two different optimization problems: one of optimal policy inference - estimate the target policy from a fixed set of collected data, and one of optimal data collection - estimate a behavioural policy that collects the best training data. For inference the currently popular data-efficient off-policy algorithms are MPO and DiME, which are used for multi-objective optimisation and differ in how they combine the various preferences across the tasks into a single policy. For the collection problem, successful approaches are for example Simple Sensor Intentions, where the agent explores by maximizing a predefined statistic/feature of the input sensors, and explore2offline, which uses Intrinsic Model Predictive Control for planning (MPC with task-agnostic intrinsic curiosity rewards).

-

Existential approaches [17-19] - these models attempt to produce fully autonomous agents with lifelong adaptive capabilities, able to succeed and generalize across different domains. In a way, with enough autonomy in the goal, this tackles existential problems (for lack of a better word) like goal generation & selection, self-recognition, and multi-agent cooperation. Of course, it is still early to judge the practical merits of these algorithms. Nonetheless, they hold their ground as one of the most interesting ideas in current RL.

All in all, IMOL 2022 proved that research in optimizing the exploration-exploitation trade-off is alive and kicking. Some of the hot topics include architectures for better generalization, data-efficient offline RL, and better ways to incentivize exploration in sparse reward environments. Other topics like entire cognitive architectures are slowly but steadily getting traction.

That being said, it seems to me that:

-

Current research in intrinsic motivation may be too anthropocentric, specifically in areas like developmental robotics where the focus is on imitating specifically human learning. I think this focus on the humans may be hindering progress a bit because of how complex humans are. Moreover, who said that human learning is the best example of early developmental learning?

-

I'm starting to develop a fairly strong preference toward more minimalistic models. For example, some of the researchers I spoke to held this notion of social interaction as an almost fundamental "generator" of useful signals for humans. While I do agree that social interaction is a key part of our behaviour, I believe it can easily be abstracted away into the environment. Agents cooperating to solve tasks together should be able to invent social norms in a way that allows them to solve tasks more efficiently. In that sense social interaction is not something fundamental, it's just a tool. And the current attitude towards these kinds of issues is not "reductionist" enough.

-

We need better goal and action abstraction that go beyond the simple "goal - reward" duality. In economics we know that only some preference relations admit a utility function representation. What if this implies that there are goals that cannot be described with a reward function? In essence, I believe that if we have better abstractions for concepts like goal and action, then it would be easier to optimize over goals and recognize and invent new actions - a step toward more general agents.

In conclusion, IMOL 2022 was a ton of fun. I met some very smart and interesting people and our discussions have given me important perspective. Looking forward to the next one.

References

[1] Binz, M. and Schulz, E. Exploration With a Finite Brain arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.11817 (2022).

[2] Dumini, N. et al. Intrinsically Motivated Open-Ended Multi-Task Learning Using Transfer Learning to Discover Task Hierarchy arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.09854 (2021).

[3] Gama, F. et al. Active exploration for body model learning through self-touch on a humanoid robot with artificial skin arXic preprint arXiv:2008.13483 (2020).

[4] Degrave, J. et al. Magnetic control of tokamak plasmas through deep reinforcement learning Nature (2022).

[5] Wurman, P. et al. Outracing champion Gran Turismo drivers with deep reinforcement learning Nature (2022).

[6] Der, R. and Martius, G. A novel plasticity rule can explain the development of sensorimotor intelligence arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.00835 (2015).

[7] Seitzer, M., Schölkopf, B. and Martius, G. Causal Influence Detection for Improving Efficiency in Reinforcement Learning arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.03443 (2021).

[8] Gumbsch, C., Butz, M. V. and Martius, G. Sparsely Changing Latent States for Prediction and Planning in Partially Observable Domains arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.15949 (2022).

[9] Riedmiller, M. et al. Collect & Infer - a fresh look at data-efficient Reinforcement Learning Conference on Robot Learning (2021).

[10] Abdolmaleki, A. et al. A Distributional View on Multi-Objective Policy Optimization arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.07513 (2020).

[11] Abdolmaleki, A. et al. On Multi-objective Policy Optimization as a Tool for Reinforcement Learning arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08199 (2021).

[12] Lambert, N. et al. The Challenges of Exploration for Offline Reinforcement Learning arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.11861 (2022).

[13] Whitney, W. et al. Decoupled Exploration and Exploitation Policies for Sample-Efficient Reinforcement Learning arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.09458 (2021).

[14] Riedmiller, M. et al. Learning by Playing - Solving Sparse Reward Tasks from Scratch arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.10567 (2018).

[15] Hertweck, T. et al. Simple Sensor Intentions for Exploration arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.07541 (2020).

[16] Groth, O. et al. Is Curiosity All You Need? On the Utility of Emergent Behaviours from Curious Exploration arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.08603 (2021).

[17] Sadeghi, M. et al. Gestalt Perception of Biological Motion: A Generative Artificial Neural Network Model IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL) (2021).

[18] Colas, C. Towards Vygotskian Autotelic Agents : Learning Skills with Goals, Language and Intrinsically Motivated Deep Reinforcement Learning PhD thesis, Université de Bordeaux (2021).

[19] Akakzia, A. et al. Help Me Explore: Minimal Social Interventions for Graph-Based Autotelic Agents arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.05129 (2022).