Spherical Harmonics

Spherical harmonics are a nice little mathematical tool that has found big applications in computer vision for modeling view-dependent light. The first time I encountered them was in the Plenoxels paper and I've been meaning to explore them ever since. Apart from the mathematics, there's not much to worry about, it's actually quite pleasant.

We start with some motivation from computer graphics. Consider that, due to light being directional, in 3D we can think of the incoming and outgoing light directions as points on a unit sphere. The rendering equation defines the radiance at a surface point \(\mathbf{p}\) that goes out in direction \(\mathbf{v}\). It consists of the emitted light from point \(\mathbf{p}\) in that direction, summed with the reflected light towards \(\mathbf{v}\) from all incoming directions:

Here \(\lambda\) is the wavelength, \(\Omega\) is the hemisphere of all incoming directions \(\mathbf{s}\), \(\mathbf{n}\) is the surface normal at point \(\mathbf{p}\), and the BRDF controls the precise way in which light is reflected. Diffuse surfaces reflect light uniformly in all directions, while specular surfaces reflect in a mirror-like way. Most natural surfaces have both a specular and a diffuse component.

As another example in radiometry, the radiance, or the emitted electromagnetic energy, is also measured in a directional way. The total power of light emittance by a physical object is called radiant flux. If we differentiate it with respect to direction, we get radiant intensity. If we further differentiate it by its surface area, we get radiance. Thus, when it comes to waves, it is important to be able to model directionally-dependent quantities.

In vision, when reconstructing 3D scenes, for example using neural radiance fields, it is common to have the network model a function like \((\mathbf{p}, \theta, \phi) \mapsto \mathbf{c}\). If we only predict the RGB color \(\mathbf{c}\) from the point coordinates \(\mathbf{p}\), without consider the viewing direction \((\theta, \phi)\), then the point will look the same from all directions, which may be unrealistic. Thus, usually we condition the generated color to depend on the viewing direction. Spherical harmonics are a different way to achieve this.

The Laplacian of a function \(f(x, y)\) is given by \(\nabla^2 f = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2}\). Any function \(f\) for which \(\nabla^2 f = 0\) is called a harmonic. This property entails a certain smoothness to the function. To see why, consider the Laplacian operator applied on images, in which case it's called the Laplacian filter. It looks like the following convolution kernel.

It takes the difference between the value at the central point and the average value of the surrounding points. When scanning it along an image, it produces a peak whenever a change in intensity is detected. Intuitively, this Laplacian is equal to zero whenever the central value is exactly equal to the average of the surrounding values. In that regard, the function is smooth.

This interpretation of the Laplacian as a measure of how different the current point is from its surroundings is very important. It is present for example in the heat and wave equations:

The heat equation tells us that the speed with which some quantity \(f\) at a particular point \(\mathbf{x}\) changes depends on the different of \(f\) at that point, and the surrounding points. So if we imagine a flat plane and an infinitely tiny region which is warped (a bit like how they represent singularities in space-time), then at that particular point that difference (Laplacian) will be very large in magnitude. The velocity with which \(f\) changes at this point will be proportional to how curved \(f\) is at that point.

The same notion of curvature is used in the wave equation, except that now it tells us that the acceleration of \(f\), not the velocity, depends on it. This small change leads to big qualitative differences as it usually introduces offershooting dynamics causing \(f\) to oscillate, which in turn gives rise to waves. Depending on the boundary conditions waves can propagate radially, or interfere between each other, or be standing waves. But the general idea is that the acceleration of some quantity depends on the difference between the specific value and the surrounding values.

Now back to spherical harmonics, they are functions defined on the surface of a sphere. Naturally, they are smooth. They do not have any isolated local maxima (or similarly minima). This means that there is no point \(x^*\) on the sphere where the harmonic has a local maximum (there exists a small neighborhood around \(x^*\) where the values are all smaller than the value at \(x^*\)) that is also unique in attaining this value across the whole domain. For example, the function \(\sin(x)\) has a local maximum at \(\pi/2\) but it is not isolated, because there are other local maxima at \(\frac{5\pi}{2}, \frac{9\pi}{2}, ...\) which attain the same value.

With spherical harmonics there are no isolated local extema. There may be local maxima and minima, but they are not isolated. Any increase in the function needs to be offset by a decrease somewhere else. An intuitive way to think about this is through the Laplacan filter kernel for 2D images. The versions presented above are \(3\times3\), but we can extend them to \(5\times5\) and beyond:

This filter computes the same Laplacian but considers a larger context window compared to the \(3\times3\) one. If we imagine an even bigger one, it becomes clear that it is entirely possible to have a high-value region within the neighborhood, as long as there are also points somewhere in it that are sufficiently negative so as to balance it out.

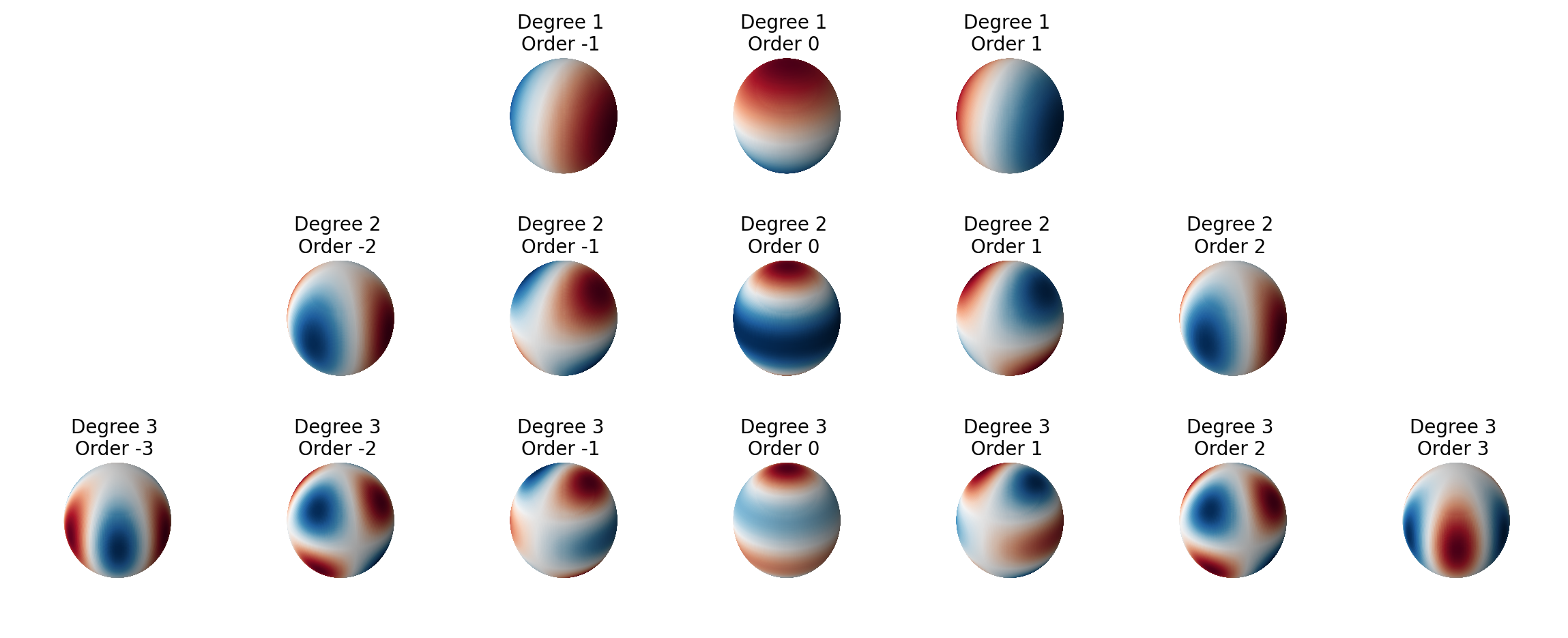

Figure 1 shows a few spherical harmonics (only their real part really). Each of them has specific degree and order parameters. The order, called \(m\), represents the number of waves we can count if we trace the sphere horizontally along a constant latitude. If \(m=0\), the harmonic has no variation along the longitude and is symmetric around the polar axis. The degree, typically called \(\ell\), represents the number of latitude (horizontal) variations or bands that the function will have. If we trace the values on a line from one pole to the other, it will have \(\ell - |m|\) zero-crossings. A particular harmonic is written as \(Y_\ell^m\).

Derivation

Let's look at a high level derivation, without too much mathematical details. We are looking for functions \(f: \mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb{C}\) for which \(\nabla^2 f = 0\). We start with the Laplace equation in spherical coordinates (its derivation can be found here):

where \(\theta\) is the inclination angle, \(\phi\) is the azimuth, angle ranges are \(0 < \phi < 2\pi\), \(0 < \theta < \pi\). The boundary conditions ensuring periodicity are \(f(r, \theta, 0) = f(r, \theta, 2\pi)\) and \(f_\phi(r, \theta, 0) = f_\phi(r, \theta, 2\pi)\). Additionally, the most important boundary condition is \(f(r, \theta, \phi) = g(\theta, \phi)\), which expresses the idea that we are considering to model some particular function \(g\) depending only on the direction \((\theta, \phi)\), not the radial distance.

Let's assume that \(f\) factorizes as \(f(r, \theta, \phi) = R(r)\Theta(\theta)\Phi(\phi)\). After substituting and rearranging, we can get an expression from which \(r\) can be moved to one side:

Since the \(r\) terms can be separated from the non \(r\) terms, all of them need to equal a constant. Hence, we introduce \(-\lambda\) and get the following equations:

Now, we introduce a second separation constant, \(m^2\), in the second of these, from which we get:

The equation for \(\phi\) is a second order linear equation. Its solution, given the periodic boundary constraints, is \(\Phi(\phi) = \{\sin m \phi, \cos m \phi \}\), for \(m=0, 1, 2, ...\).

The solution for the equation for \(\theta\) is more involved. If we substitute \(x = \cos\theta\) in the second equation above and let \(y(x) = \Theta(\theta)\), then we get

Here one can assume a functional form of the type \(y(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n x^n\), that is, a generating function. Now, from studying this equation, one would get a recurrence relation for the coefficients \(a_n\), where \(\lambda\) is still to be found. Turns out the infinite series converges only when \(\lambda = \ell(\ell + 1)\), for \(\ell = 0, 1, 2, ...\). In general, the solution for \(\Theta(\theta)\) involves the so-called associated Legendre functions, which we note as \(P^m_\ell\), and is given by \(\Theta(\theta) = P^m_\ell(\cos \theta)\).

Having establishes that \(\lambda=\ell(\ell + 1)\), we can solve the radial equation by assuming a solution of the form \(R(r) = r^s\). When solving for \(s\), we get \(s(s+1) = \ell(\ell+1)\), hence \(s = \ell\) or \(s = -(\ell + 1)\). In general, after boundary conditions, \(R(r) = ar^\ell\).

Finally, the overall solution, in complex form, is given by

Since spherical harmonics arise in many cases and only their angular terms matter, it is common to combine them as follows (and this is actually the usual form):

Spherical harmonics form a complete orthonormal basis for functions on the sphere. Thus, much like how every function on the circle can be expressed as a potentially infinite series of Fourier terms, also, every function on the sphere can be expressed as a potentially infinite sum of spherical harmonics. The coefficients \(a_\ell^m\) are found as

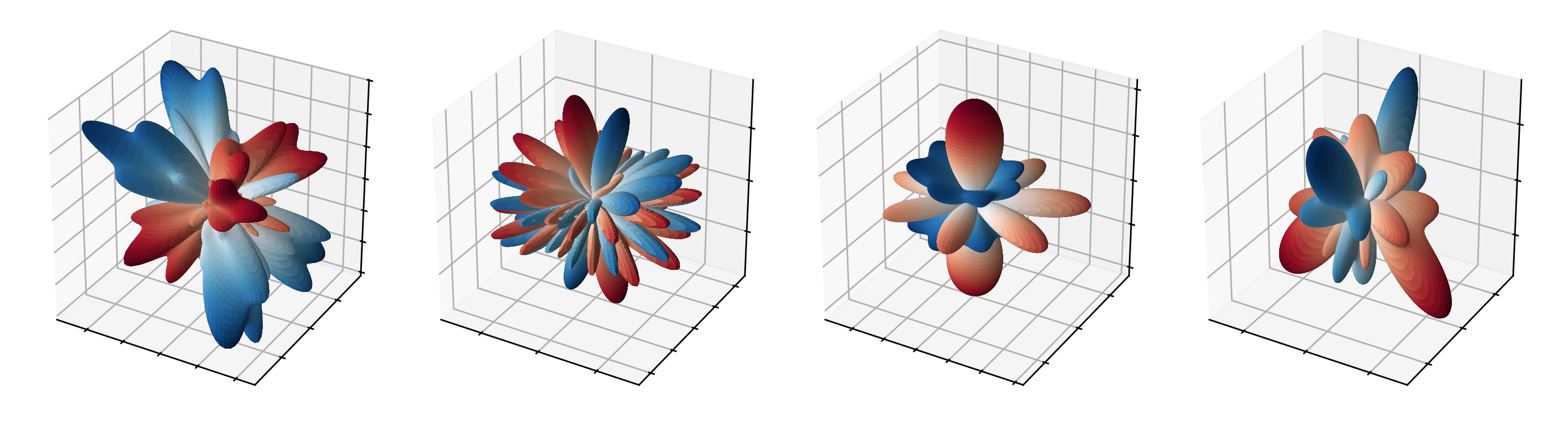

where \(\ast\) indicates complex conjugation and, finally, we are using the boundary condition \(g(\theta, \phi)\). Thus, the interesting things start to happen when we mix different spherical harmonics with different coefficients. Fig. 2 shows a few examples where we combine different harmonics and plot them by radially modulating the shape according to the magnitude.

Naturally, it is obvious that spherical harmonics can model very complicated BRDFs representing diverse specular effects. So how do we use them for machine learning? The common approach is to have the model predict the coefficients of all spherical harmonics up to a given degree, e.g. \(3\). Then, we sum them up and evaluate the joint harmonic at the requested \((\theta, \phi)\) direction. If we need to produce RGB images, and not just intensities, we can predict separate coefficients for the red, green, and blue channels and thereby simply repeat the process for each channel independently. In most implementations the evaluation is very efficient because the normalization factors for the basis spherical components are precomputed and hardcoded. Therefore the neural network just predicts the coefficients \(a_\ell^m\) for RGB separately and we approximate the light field by the the linear combination of the first few low degree spherical harmonics.