Natural Vision, An Overview

Computer vision has been progressing at a breakneck speed. Most of the improvements are quite technical and it's easy to get lost in all the myriad research directions. Here instead, we explore natural vision which offers interesting and intuitive insights on how visual perception is achieved in humans. This post covers various aspects related to human vision - the geometry, the morphology of the eye, the eye movements, and the interpretation of visual inputs by the brain. After all, if we want to build superhuman visual systems, we need to know what we're up against.

Vision is the most important sense that humans possess. It gives the most information about the environment, in sufficiently high semantic resolution, allowing us to navigate and plan. It is so fundamental that our thoughts are often represented as visual patterns. You can't really think of an elephant without picturing one in your mind. The human visual system is one of the most complicated systems out there. Approximately 30-40% of the human brain is directly or indirectly involved in processing visual information.

The first eyes started to evolve approximately 500 million years ago in trilobites. These ancient creatures had calcite-based eye lenses which directly facilitated the fossilization of the creatures and their subsequent study. Calcite itself has excellent optical properties and is perfectly suited for focusing light, but is relatively inflexible, making it unsuitable for the dynamic focusing mechanism used by many modern animals. There may be other animals which have utilized vision even before trilobites, like jellyfish, but it is difficult to say how far back in time. What is certain is that all animals which can see have rhodopsin, a peculiar molecule that is fundamental to vision.

Rhodopsin is a crucial molecule for vision under low-light conditions. It is composed of a protein called opsin and a light-sensitive compound called retinal, which changes shape when exposed to light, triggering a series of chemical reactions that ultimately create an electrical signal. In humans this signal is then transmitted to the brain, enabling us to see. The chemical properties of rhodopsin's reactivity to photons is what allows all animals to process light and therefore see.

Not all animals have good eyesight. Sponges (Porifera) don't have eyes at all. Radially symmetrical animals (Cnidaria) like sea anemones, corals, and jellyfish have only primitive photoreceptors. Bilaterally symmetrical animals (Bilateria) tend to produce animals with comparatively stronger eyesight. Of them the best eyes can generally be found in arthropods (chelicerates, insects, crustaceans), cephalopod molluscs (octopus, squid, cuttlefish), and chordata vertebrates.

In terms of actual photosensitive cellular architectures, there are two main types. Rhabdomeric photoreceptors are typically found in invertebrates like insects and crustaceans. The light-sensing part of the cell is made up of tightly packed microvilli (small projections on the cell surface) where the phototransduction machinery is located. The other type are ciliary photoreceptors, found most commonly in vertebrates. The rod and cone cells in humans are types of ciliary photoreceptors. The photoreceptive parts of these cells are located on modified cilia (hair-like structures on the cell surface) and these receptors are generally responsible for vision across a range of light conditions, from dim to bright light. The ciliary photoreceptors in vertebrates work via a hyperpolarization mechanism, meaning that when they are activated by light, the electrical charge inside the photoreceptor cells decreases.

It only takes a single photoreceptor cell to provide useful behaviour benefits. Consider that using a single photoreceptor an animal can tell day from night and by steering left and right, can tell the rough direction of the light source. Evolution has produced many improvements over this. Two types of eye designs have become stable - single chambered and compound eyes.

Single-chambered eyes have their receptors in a single concavity. They have evolved in the following architectures:

- A pigment cup eye places the receptors in a concave depression in the tissue, which allows the basic sensing of light direction, self-movement, and orientation to landmarks. Flatworms and annelids have simple cup eyes.

- A pinhole eye is a pigment cup eye where the aperture of the cup is almost closed. This allows a primitive form of imaging, but otherwise reduces the amount of light that enters the eye which often limits resolution. The abalone, some giant clams, and the Nautilus have pinhole eyes.

- A lens improves over the pinhole eye by still mapping a single point in 3D to a single photoreceptor but without reducing the amount of light going in.

- A corneal eye contains a protective cornea that in the case of land-animals became a refractive structure which took the role of the lens. This allowed the formation of dynamic accommodation capabilities in animals. The octopus, squid, cuttlefish, and the jumping spiders have extraordinary vision capabilities based on corneal eyes.

Compound eyes are made up of many small, repeating units known as ommatidia. Animals with compound eyes, like the Antarctic krill, have many independent eyes - each with a pigmented tube and a lense collecting light withing a narrow field of view. In the apposition subtype (e.g. in ants and bees) the individual ommatidia are independent and the overal image is formed by the apposition of the contributions from all individual receptors. The light entering one ommatidium doesn't mix with light entering other ommatidia. This results in a clearer, more detailed image but requires stronger light to function effectively. In contrast, superposition eyes (e.g. in moths) combine or 'superpose' light from several ommatidia before it reaches the photoreceptor cells. This results in greater sensitivity and enables better vision in low-light conditions, but at the expense of image detail.

The optical components of an eye have physical limitations to which the different animals have to adapt. The most popular such limitations are:

- Spherical aberration occurs when a spherical surface bends light rays that strike off-center more or less than those that strike close to the center. As a result the focal point becomes a focal "region" and the image becomes blurry. Various marine animals have evolved eyes where the proteins farther away from the center of the eye are diluted with more water, thus producing a gradient in the refractive index and somewhat alleviating the aberration.

- Chromatic aberration occurs when the focal length depends on the wavelength and thus some colors are bent more than others. Animals can deal with this by having different photoreceptors placed at different distances from the lense, or by having more complicated irregular lenses. In an artificial setting one can use a doublet lense made of two glass layers with different dispersions so that the individual aberration effects cancel out.

- Diffraction, or the interference and bending of light waves around corners, ultimately serves as an unavoidable limit to the resolution of the images in the eye. In the eye, light has to pass through the pupil, which acts as an opening. This results in diffraction and leads to the formation of Airy disks. The central bright disk contains the majority of the light, and the size of this disk determines the smallest detail that the eye can resolve. If two points of light are so close together that their Airy disks overlap significantly, the eye will not be able to distinguish them as separate points. This is known as the diffraction limit. The width of the Airy disk is given by \(\lambda / D\), the wavelength divided by the aperture diameter. Hence, everything else being constant, a larger pupil size improves resolution.

- Dim light poses a particular challenge to vision because the quality of the produced image depends not on the sophistication of the machinery of the eye, but simply on the quantity of photons that hit it. Light arrives as indivisible quants that are either absorbed by the rhodopsin or not. And in dark environments this signal becomes more and more sparse. It is only natural that our reconstructions suffer as well. The key to night vision is to get as much light onto the image as possible, and to pool the signals from many receptors across both space and time. With the first, the goal would be to increase the ratio of the aperture to focal length, \(D/f\). Cats and dogs have larger lenses than humans, while the giant squid has bigger eyes in general. With the second, some vertebrates can change the neural connexions in the retina, thereby increasing the number of pooling photoreceptors corresponding to a single pixel. In general, vision in the dark requires more computation and is slower.

Human Vision

Human vision mostly inherits the evolution and peculiarities of the first jawed fishes that evolved from their chordate ancestors. The lens projects 3D information onto an almost 2D retina of rods and cones. The cornea, which in land animals separates air from fluid, is responsible for about \(2/3\) of the light bending. The lense in humans is not spherical but rather flattened and can be moved around by the surrounding ciliary muscles to focus on objects at different distances. This process is called accommodation. As we age the elasticity of the lense decreases steadily. At age 1 the minimum focus distance is aroung 5cm from the eye, while at age 55 it increases to about an arm's length. Myopia and hyperopia occur when the eye's optical system is not strong enough to accommodate the lense to near and far objects.

The iris, characteristically colored in blue, green, or brown, controls the pupil diameter, or the aperture of the eye. In bright light the pupil closes down to 2mm and in the dark it opens up to 8mm. This control is part of the autonomic nervous system which is unconscious and can be itself modified by various chemical substances. The white sclera that surrounds the iris allows us to judge the direction of another's gaze with high precision which is important for social interaction.

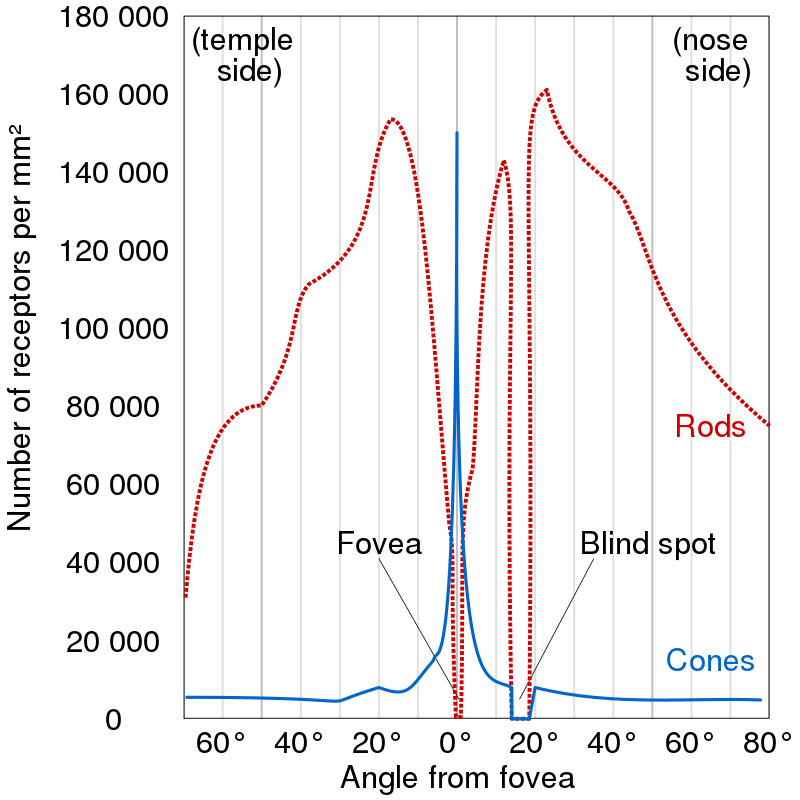

The retina contains photosensitive rod and cone cells. The former provide vision in low light settings, while the latter provide colour. The actual information processing is done by building up a voltage difference in each cell with respect to the outside, and transmitting this voltage to the subsequent bipolar cells which can detect increases or decreases in the light. From there, the signals are passed to the ganglion cells which respond to circular patterns (receptive fields) in local contrast. The ganglion cells produce all-or-none action potentials which are transported across long axons and collected into the optic nerve. This is the main pathway, receptop-bipolar-ganglion. In reality, there are additional types of cells which process the signals along this pathway.

Since the optic nerve connects to the retina, it needs to displace some of the photoreceptors, creating a small spot with no photoreceptors and hence no vision. This is called a blind spot. We don't notice it because the blind spots in our two eyes don't overlap in our visual field and the brain uses the information from one eye to fill in the blind spot of the other eye. One can notice the blind spot when he closes one of his eyes and moves an object across his field of view until it disappears and reappears again.

The retina is not uniform. Both the cornea and the lense have a single axis and the image is best resolved where this axis meets the retina. The corresponding region in the retina is called a fovea and it has the highest concentration of cone cells. It is from here that we get all our information about colour and detail. The region outside of the fovea can be thought to be responsible for peripheral vision only. In fact, the human peripheral vision is bad - we can get a sense of object motion and contours, but we can't really resolve details. Try to resolve letters in a word one or two away from the one you're looking at now and you'll be convinced.

Eye Movements

It takes about 20 ms for a retinal cone to respond to a change in the intensity. In angular space this is about 1 degree per second. Hence, anything moving faster that that will not be properly resolved. Turns out that when we scan a scene, we don't move our gaze (the region of the 3D scene in which we focus) in a smooth way, because that will introduce a lot of motion blur. Instead, humans as well as all other vertebrates, employ a saccade-and-fixate strategy. Saccades are quick movements of the eyes lasting about 30ms that change the gaze. Inbetween each saccade, there is fixation where the cones resolve all the details. In this sense, human vision is recurrent and iterative.

Our eyes move with respect to our head. But our head moves with respect to the body. Therefore, to stabilize the gaze on a fixed 3D point, the eye needs to compensate for the movement of the head. The vestibulo-ocular reflex handles this by training the eye to move inbetween saccades in a way opposite to that of the head, so that in fact you are able to fixate a single 3D point while the head is moving.

Apart from saccades and fixation, there is also smooth pursuit and vergence movements. Smooth pursuit is a voluntary and occurs when the eye is tracking an object that doesn't move with more than 15 degrees per second, after which the eye movements will become increasingly saccadic. Interestingly, smooth tracking cannot occur on imaginary objects, presumably because there is no external signal to trigger the various retinal machinery. Vergence is the only eye movement where the two eyes move in opposite directions. It happens when a fixated object moves in depth. Finally, there is also a lot of complexity related to how the commands from the cerebral cortex translate to the muscles which move the eyes.

It is generally unknown what determines where we look at next. Novel objects in view will almost always trigger saccades, but apart from that it is believed that the eye movements are not reflexive, but are governed by a plan for moving the fovea around to those parts of the scene likely to yield the most relevant information. Similarly in the vision-to-motor-control loop, gaze is typically ahead of each motor action by about a second. Be it in copying text, reading music notes, driving, or any other common action, the eye movement system directs gaze in a prospective way, to those regions which are relevant to the task. And in those tasks where time is critical, like ball sports, saccadic movements are performed based on the expected position of the object of interest.

Depth

The image produced by the retina is, rougly, a projection of the 3D scene onto a 2D plane. Necessarily, with only one eye, some information is lost. Simply, the depth of each pixel, i.e. the distance of the 3D point corresponding to that pixel to the image plane, is unavailable in images. With two eyes explicit depth information is available, as long as the two eyes have overlapping fields of view. To perceive depth animals have evolved to interpret various binocular and monocular cues.

Binocular disparity, is a critical binocular cue for depth perception that arises due to the horizontal separation between the two eyes. Owing to this separation, each eye produces a slightly distinct image of the environment, resulting in two disparate retinal images. Essentially, a 3D point is projected into two different retinal points, relative to the centers of the two foveas. The horizontal difference between these coordinates is the disparity. It is large if the 3D point is close to the eyes, and small otherwise. This is the main visual pattern that allows depth estimation.

And the perceived depth is relative. Suppose there are two 3D points with different depths, and both eyes are focused on the closer point. Then the retinal disparity is proportional to \(D/V^2\) where \(D\) is the depth difference between the two points and \(V\) is the absolute difference between the focused point and the center between the two eyes. Thus, disparity alone does not provide absolute depth information, only relative depth with respect to the object which is focused. However, if the two eyes are converged on the closer object, the angle between their axes gives a fair measure of the absolute distance \(V\). From there, the relative distance can be calibrated. It is not necessary for a known object to be recognized in the scene in order to perceive depth.

It is impossible to compute exact depth from a single image. However, nothing prevents the brain from hallucinating depth and combining its estimates with factual knowledge about how big different objects are. The actual monocular depth estimation relies on many learned visual patterns - relative size, perspective, texture, elevation, occlusions, etc. All of them serve to guide the brain in estimating the depth for each object in the visual feed.

Another important depth cue comes from motion, where it's called optical flow. Objects closer to the eye move faster across the retina than distant objects. If we are moving forward with constant velocity and no rotation, then the objects moving across the retina trace out trajectories across space and time. At any point in time, a single pixel moves according to a flow field consistent with our motion in the scene. This flow field has a distant point (pole) from which the flow, represented as velocity arrows, originates. This point is the current heading direction. The velocity of the seen objects depends on how much their movement is aligned with our heading direction and how close they are to the pole. Furthermore, the flow field allows for calculation of time-to-impact and looming effects, all of which are useful for decision-making and actuation.

The biggest question is how does the brain backproject all the depth cues such that a consistent 3D representation of the world is formed. It is currently unclear how to even state the problem...

Colour

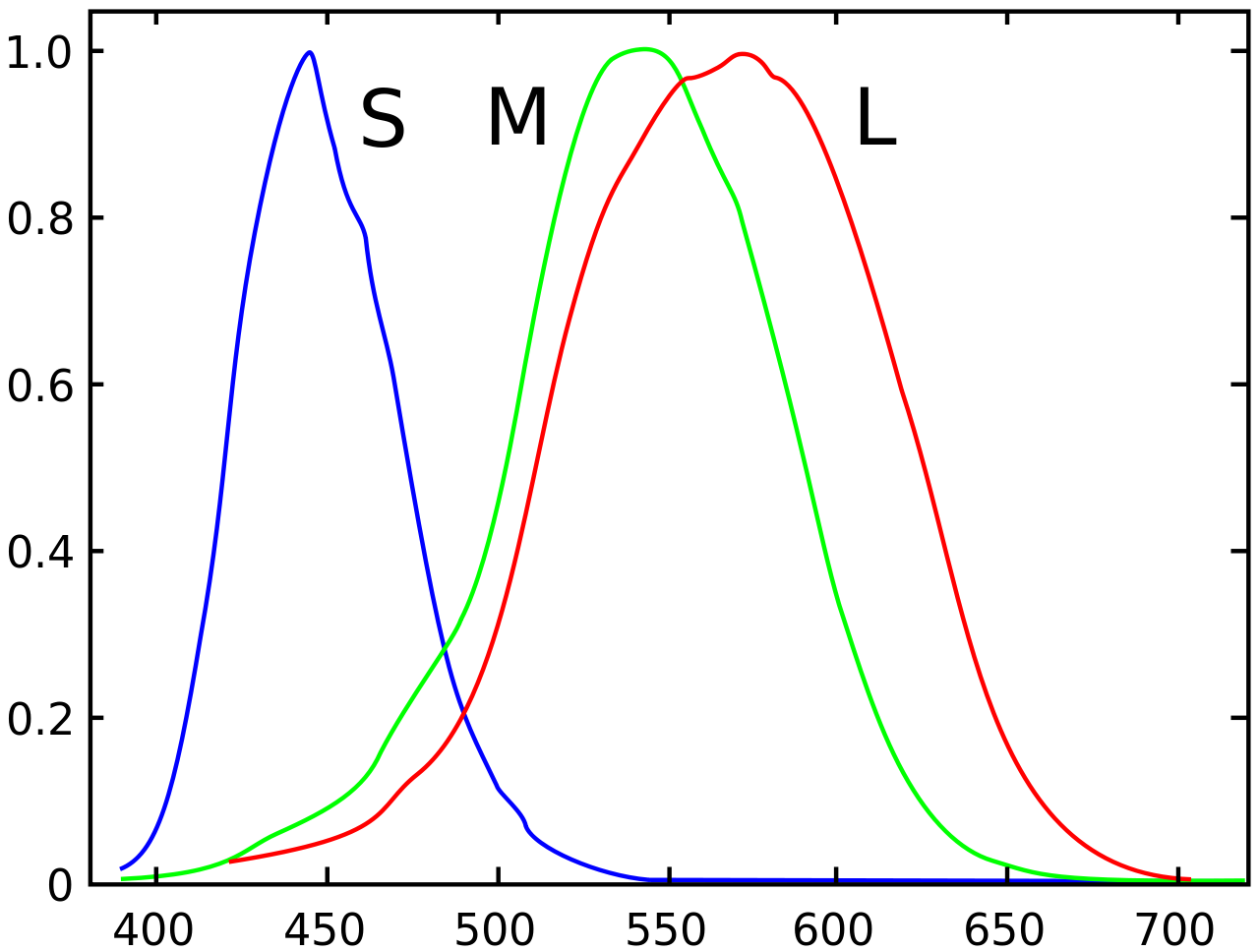

Light does not have objective colour. Light is just photons of different energies or waves of different wavelengths. The colours we perceive are completely subjective. In the human retina there are rod cells and three types of cone cells. The sensitivity distribution of all of these cells overlaps considerably in some regions. The rods are maximally sensitive to blue-green light (about 498 nm) and are not involved in colour vision. The cones are sensitive to short, middle, and long-wavelengths (S, M, L) . These correspond to blue-violet (419 nm), apple-green (531 nm), and yellow-green (558 nm). Note that it has been long known, and verified experimentally that pretty much all real-world colours that we see can be created by mixing red, green, and blue (RGB). This is a fact that relies on the subjective way humans see colour. The observation that our L cones are not maximally sensitive to exactly red should not be shocking. Red is simply defined as that colour which activates the L cones fairly well, but does not trigger the M cones at all.

Consider that a given light will trigger all three types of cones to different extents. We can represent the particular hue as the triplet containing the percentages that each cone is activated. If the light level decreases, the hue does not change, only the lightness changes. This motivates the disentanglement of colour and intensity. Moreover, to understand intuitively that it is the cone ratios that define hues, consider what happens with only a single cone. With a single cone, there can be two different wavelengths that trigger the cone to the same extent, thus making coloured vision impossible.

Colour information is not represented simply as responses from the (S, M, L) cones. The ganglion cells mentioned above have a colour opponent structure where there are two colour channels - one responding e.g. positively to red (L), negatively to green (M), and another positively to blue (S), negatively to yellow (L + M). There is also a luminance channel formed from the summed responses of the red (L) and green (M) channels. This is how the image leaves the ganglion cells and reaches the cortex where the heavy pattern recognition starts.

Colours require specialized mathematical treatment. The colour of a mixture of lights of different wavelengths is additive. If you shine red light and green light together into your eyes, both the L and the M cones in your eyes are stimulated. The signals from these cones are then sent to the brain, which interprets this combination as yellow, even though there are no L + M cones in the eyes. On the other hand, mixing pigments requires modeling subtractive colours. This is because pigments absorb what they don't reflect. If we mix yellow and blue pigments, we get green because green is the only light that is reflected back from both pigments. In general different mathematical models exist based on different aspects like additivity, perceptual uniformity, and linearity.

Interpretation

The path through photoreceptors, bipolar cells, ganglion cells, and optic nerve is only the beginning of the visual pathway. The optic nerves from each eye split into two, cross each other and two-by-two proceed into the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), deep within the thalamus. The splitting and crossing occurs so that the two images can be brought together in the cortex where depth can be calculated. After the LGN, the signals are relayed to the primary visual cortex, or \(V_1\), inside of the occipital lobe of the cerebral cortex.

Here, inside \(V_1\) starts the massively parallelized pattern processing. \(V_1\) is a region of the brain where individual signals localized on the retina are mapped to individual corresponding neurons, this process being called retinotopy. The neurons here are organized into six functionally distinct layers stacked on top of each other and do not respond to concentric receptive fields like in the retinal ganglion cells, but rather to lines, edges, and similar patterns across different orientations. How each neuron has decided which patterns to look for within its receptive field is called neuronal tuning and it may include preferential attention towards patterns from one particular eye (occular dominance). Those neurons which have similar tuning properties tend to cluster together into hypercolumns, also called cortical columns, spanning all six layers of \(V_1\) and standing perpendicular to the cortical surface. The colour information which is available from the colour-opponent cells in the retina is sequestered in "blobs" that also go through the hypercolumns. How colour information is utilized is still uncertain though. All in all, one hypercolumn corresponds to one pixel in the processed image.

The currently dominating belief for what happens after \(V_1\) is the two-stream hypothesis. It states that after \(V_1\), the signals are relayed to two different pathways. The first, called the ventral stream leads to the temporal lobe which deals with the "what" question of object detection and visual identification. The second pathways is called the dorsal stream and leads to the parietal lobe where it answers the "where" question of object localization. The hypothesis was modified in 1990 to associate the ventral stream with perception, and the dorsal one with control of actions. At this point multiple other regions in the brain may get triggered with the processed visual input. The motor cortex may react to the localization signals from the dorsal stream and may direct the muscles towards some goal. The amygdala may react to patterns of fearful and angry faces from the ventral stream. The hippocampus may be prompted to constructs and utilize mental maps for self-localization or to translate them into egocentric coordinates for better navigation.

Conclusion

Clearly, human vision is a complicated matter. We have evolved complex systems which manage to squeeze out the maximum efficiency and performance possible. There are so many open problems that it might be daunting to even think about them. Yet, there are also many opportunities for borrowing ideas from natural vision into existing computer vision solutions. I expect this will be highly beneficial. What a time to be alive. For a more comprehensive overview I recommend this book, as it's the one I've based this post on.