Video Coding and MPEG

I find the topics of image analysis and video compression very enjoyable. A previous post has covered JPEG, the most widely used image compression standard. Now it's time to explore the MPEG standards, at least some of them. This is a super important topic, as videos are too large to store or stream across the internet in their raw format. So we necessarily need efficient compression algorithms. And there is some solid math, like the DCT, as well as various engineering tricks, like quantization and predictive coding, involved in them...

Media files often contain multiple streams - video, audio, subtitles, etc. These need to be synchronized correctly such that the right frames and sounds appear at the right time. Media containers, also known as wrapper formats, are file formats that can contain various types of data, such as video, audio, metadata, subtitles, and more. They package these streams together, allowing them to be played, streamed, or saved as a single file. Popular containers are mp4 (MPEG-4), mkv (Matroska), avi (Audio Video Interleave), mov (QuickTime File Format), webm (WebM by Google). There is considerable difference between containers - they have different supported codecs, owners, and licenses. Some support metadata, video chapters, and interactive menus, others do not.

The process of bundling invidividual streams together is called multiplexing (or muxing). Usually a muxer takes the raw data streams and breaks them into packets suitable for the chosen container format. Then, metadata about the codec, bitrate, and resolution is added according to the specific format of the container. For example, the Matroska container allows a simple file to have just two elements: an EBML Header and a Segment. The Segment itself can contain all the so-called top-level elements: 1) SeekHead, containing an index of the locations of other top-level elements in the segment, 2) Info for metadata used to identify the segment, 3) Tracks storing metadata for each video & audio track, 4) Chapters, 5) Cluster contains the actual content, e.g. video-frames, of each track, 6) Cues for seeking when playing back the file, 7) Attachments for things like pictures & fonts, 8) Tags containing metadata about the segment.

The reverse process of obtaining individual streams from a single container file is called demultiplexing (demuxing). Here the demuxer reads the container and based on its structure extracts data into separate streams - one for video, possibly many for audio (e.g. different languages) while keeping the streams time-synchronized.

The extracted data streams can be either compressed or not. Without video compression even the shortest videos become unnecessarily large. For example a HD video with resolution \((1280, 720)\), 24 frames per second (fps), 3 bytes per pixel, 1 minute long, takes about 3.7 gigabytes for storage, and requires \(\approx\) 0.5 Gbps when streaming. This is too much. Using a proper video codec, the combination of an encoder and a decoder, one can enjoy sometimes up to 200:1 compression ratios without a drastic reduction in the quality of the reconstruction.

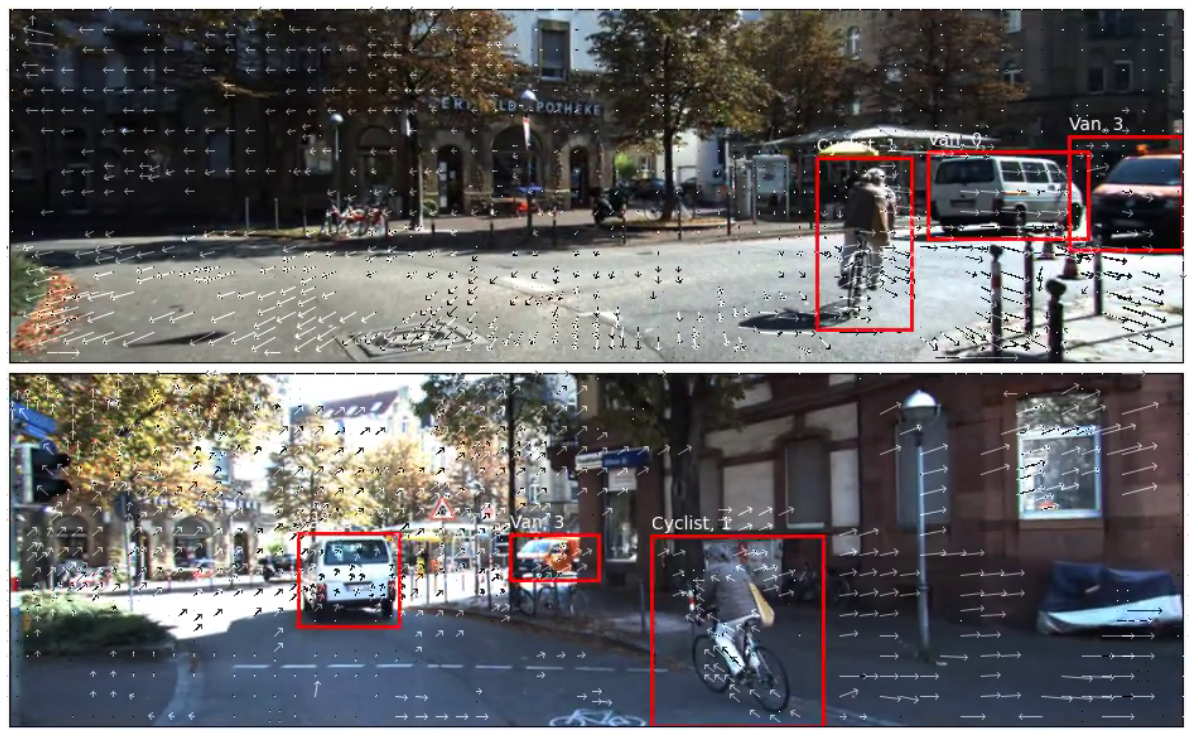

Most codecs rely on the discrete cosine transform (DCT) and motion compensation. Natural videos contain a very high amount of temporal redundancy between nearby frames, and spatial redundancy between individual pixels within a single frame. Inter-frame compression utilizes nearby frames and codes one frame based on a previous one, which requires storing just the differences for those pixels which have changed. Intra-frame compression instead utilizes information from within a single frame and very much resembles the ideas in the JPEG standard.

The inter frame coding attemps to express the current frame in terms of previous ones. More specifically, the current frame is divided into macroblocks. These consist of \(16 \times 16\) elements. There are two types of macroblocks - transform blocks, which will be fed to a linear block transform, and prediction blocks, which are used in the motion compensation.

It is common to work with macroblocks not in RGB but in the YCbCr colour space. It is known that human vision is more sensitive to changes in the luminance Y than to changes in the chrominances (Cb is the difference between blue and a reference value and Cr is similar but for red). This allows us to subsample the chroma channels without much perceptual degradation in the image quality. Usually a chroma subsampling ratio of 4:2:0 is used. To understand what this means, one can imagine a region of pixels of width 4 and height 2. In the first row of 4 pixels the chroma channels will be sampled in regular intervals exactly 2 times. Then, the 0 indicates that there are a total of 0 changes in the 4 chroma values across the first row and the second row. Overall, this yields a 50% data reduction compared to no subsampling.

The temporal prediction happens, in reality, at the level of a macroblock using a block matching algorithm. Suppose we have a macroblock from frame \(t\) and we want to find the most similar macroblock from frame \(t-1\). Once we do that, we can encode the current macroblock with a motion vector pointing to the found past block, along with any residual information that has changed. Exhaustive search for the most-similar previous macroblock is prohibitive. It is common to only search the macroblocks which are up to \(p=7\) pixels on either side of the corresponding macroblock in the previous frame.

For evaluating the similarity between two blocks \(C\) and \(R\), both of shape \((N, N)\), it's common to use the mean absolute difference (MAD), mean squared difference (MSE), or the peak signal-to-noise ration (PSNR):

To find the best matching macroblock, one can always resort to brute force search. This involves computing the cost functions above for every possible macroblock within the \(p\) pixels difference on each side. For \(p=7\) this involves 225 cost function calculations. A much faster, but less accurate approach is the three step search algorithm which evaluates only 25 candidate macroblocks. Suppose the block in the past frame corresponding to the current one has centered coordinates \((0, 0)\). Then in the first step we set \(S=4\) and we evaluate the blocks at \(\pm S\) pixels from \((0, 0)\), along with \((0, 0)\) itself. This is 9 evaluations. Then we center the current coordinate around the most similar block. In the second step we repeat with \(S=2\) and in the third with \(S=1\). When \(S=1\) the macroblock with the smallest block is selected. There are many other algorithms, each offering various speedups to the basic block matching idea.

Even the best-matching found block may not match exactly. For that reason the encoder takes the difference, called the residual, and encodes it. Note that nothing prevents the encoding of the past macroblock to itself depend on yet another previous macroblock. Thus, motion prediction can be recursive, but obviously not infinitely... This motivates a distinction between how frames can be encoded:

- I-frames (Intra-frames) are self-contained frames in a video sequence that are encoded without referencing any other frames. They serve as reference points for subsequent predictive frames (P-frames and B-frames) and act as "reset" points in a video stream, allowing for random access and error recovery.

- P-frames (Predictive frames) are frames containing at least one macroblock encoded using data from previous I-frames or P-frames as a reference to reduce redundancy. They are represented as a set of motion vectors for the predictive macroblocks along along with the additional residual data.

- B-frames (Bidirectional frames) are encoded using data from both previous and subsequent I-frames or P-frames, exploiting temporal redundancy from two directions. These can yield the highest compression amount compared to the size of I-frames.

Based on the temporal and spatial relationships one can define the Group of Pictures (GOP) structure. Typically it looks like IBBPBBIBBPBBI... The first frame is an intra-frame which is self-sufficient to decode. The next two B-frames are decoded from the first, I-frame, and the fourth, P-frame, which itself depends on the I-frame. The periodic I-frames serve to reset the errors which may accumulate. The ample use of B-frames increases the overall compression ratio but forces us to transmit the frames out of order, as we need to submit the subsequent P-frame before the B-frames. This also introduces a bit of decoding latency.

Finding the closest matching macroblock from a previous reference frame yields a motion vector and a residual block. The residual block is what gets encoded similar to how it's done in JPEG. First the discrete cosine transform (DCT) is used to obtain the coefficients for the strength of the various spatial frequencies. For a square image \(f(x, y)\) of size \((N, N)\) the Type II DCT \(F(u, v)\) is given by

Modern codecs like H.264/AVC actually use a close approximate of the DCT called the integer transform. It looks something like \(\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{C} h \mathbf{C}^T\), where \(h\) is a macroblock and \(\mathbf{C}\) is a fixed matrix, predefined by the standard, which consists only of integers. Compared to the DCT, this transform is faster to compute and is exact when decoding, thereby reducing possible ringing artifacts.

After the frequency coefficients are computed, they are quantized. This can be done simply by dividing each coefficient by another integer and then rounding:

Typically the coefficients corresponding to the higher frequencies will be divided by a larger number, as differences between nearby high frequencies are more or less imperceptible. After quantization many of the coefficients are zero. This operation is the one most responsible for the overall size reduction.

After quantization, the coefficients are run-length encoded and finally entropy-encoded, either using Huffman or arithmetic coding. These algorithms are called entropy codes because they approach the fundamental compression limit given by the entropy of the underlying data. This is an almighty result. Due to Shannon's source coding theorem, it is known that the expected code length cannot be lower than the entropy of the source. If \(x\) is an event from a probability distribution \(P\), \(\ell(\cdot)\) is the length operator which counts the number of symbols in a codeword, \(d(\cdot)\) is the coding function, and \(b\) is the number of distinct symbols from which a code is made, then

After encoding the residual information, the resulting codes are transmitted or stored as a bitstream. For the purpose of broadcasting, additional error correction coding might be added to recover from potential bit errors during transmission. For streaming, multiple versions of the content are encoded at different bit rates. Depending on the viewer's network conditions, the appropriate bit rate stream is delivered dynamically.

The encoded data is what gets fed into the muxer for containerisation. Note that modern codecs like H.264, also known as MPEG-4 Part 2, are based on the ideas above but use many additional low-level improvements. For example:

- Dividing the macroblocks into partitions and estimating a motion vector for each partition,

- Subpixel motion compensation using interpolation, yielding more accrate block matching,

- Multiple past reference blocks predicting a single current block,

- Improved entropy coding algorithms like CABAC used in AVC and HEVC.

This is the main idea behind video coding. At this point, various programs can modify the video data as needed. Programs like ffmpeg can transmux data from one container to another, filter or process the decoded raw frames, or change the codec for any one datastream. Video players demux, decode and render the raw video frames, sometimes using hardware acceleration. Streaming platforms typically encode into adaptive bitrates in order to handle different client transmission demands, and so on. Such video processing has become ubiquitous.