LLM Agents

LLM agents are systems where a LLM is integrated with other components that allow it to better plan or act in a more autonomous manner. Recently, the term agentic design patterns has been used to describe the particular solutions that go in this direction. Given that LLMs have now been used for all kinds of things - solvers, planners, schedulers - the question of how to extend them to real-world tasks requiring more autonomy is ever more pertinent.

A core aspect of language modeling is that many things, including facts, questions, tasks, goals, and answers can be expressed as language. Thus, language provides a unified interface to all of these. And when we build a big model, trained on internet-scale datasets containing high-quality data, the model can be finetuned to respond to questions, write code, or otherwise start to generalize across tasks and responses. At inference time, LLMs are kind of agentic, because being autoregressive, their future outputs depend on their past outputs, in other words their predictions are consequential. Then, the appeal for using their autoregressive token processing architectures as general reasoning engines should be evident.

Agentic LLMs wrap the actual language model into a bigger software system that provides more capabilities. It typically consists of:

- A memory module that stores various kinds of memories, which is useful for problem solving,

- A planning module to iteratively refine the predictions of LLMs,

- An action module which allows the LLM to act in the world, for example by using tools, executing code, making choices, or calling APIs.

Memory

RAG. The current dominant approach to handling factual memories is retrieval-augmented generation. Here the idea is that facts will not be stored in the model's weights, but in an external authoritative database which will be queried and referenced by the model in order to produce a response. Hooking up the LLM to a database like this is useful because it allows for the easy insertion, deletetion, and mutation of facts without retraining the model. It also largely eliminates hallucinations since the model does not have to come up with the facts, but only has to retrieve them from the database and summarize them.

The idea has been floating at least since 2017 [1]. The main system takes the user query, encodes it and passes it to a retriever module which interacts with the database. All the documents from the database have been encoded previously and the system supports an operation that finds the relevant documents given the query. Once we retrieve the relevant documents, the language model reads and summarizes them. Compared to mundane user tasks, here it's beneficial to have very large context, so that the model can read all the information from the retrieved documents.

Retrieval. For retrieving relevant documents, different schemes exist:

- \(\text{tf-idf}\) [2], a classic approach uses two terms: the term-frequency \(\text{tf}\), which measures how often a term occurs in a document, and inverse document frequency \(\text{idf}\), which is the inverse of how common a term is across all documents. For all documents and terms, say \(D\) and \(T\), we compute a matrix of shape \((D, T)\) which contains the multiplication of the \(\text{tf}(t, d)\) and \(\text{idf}(t, D)\). This number is high for those terms and documents for which the term is specific and appears only inside them and in no other documents. Then, we compute \(\text{tf}(t, \text{query})\), which is a vector, and match it with \(\text{idf}(t, D)\) from which we obtain the closest neighboring documents from the database.

- Dense vectors are more flexible because they can match by term semantics rather than exact wording, which allows for answering questions which can be potentially unspecified [3]. Here we encode the documents using some model and compute a simple cosine similarity between the query and the documents. This allows finetuning the retrieval based on downstream tasks.

- Search engines can also be used for retrieval [4]. Their benefit is that they can use additional information such as recency, authorship, page ranks, or other metadata.

With learnable document encodings and a learnable retriever, people have fine tuned entire RAGs in an end-to-end manner, even along with the LLMs [5, 6]. One interesting problem in that setting is when knowledge conflicts occur [7], e.g. what happens when the parametric knowledge of the model is different from the contextual knowledge from the documents? Can we bias the model towards choosing one or the other?

Similarity search. Looking for the document vectors that most closely match our query, e.g. by cosine distance, is a form of maximum inner-product search. It is impractical to scan the entire document database. Instead very clever algorithms implement approximate nearest neighbor search. Meta's FAISS is popular. It partitions the data points into clusters. To search we perform rough quantization on the query and find out which clusters are worth searching in. The process repeats within the cluster using finer quantization.

Working memory. This is another type of memory related to how much "current" information the model can work with at any given time. In humans, consider multiplying 786525 by 25125 in your head. Usually, somewhere along the computations you will run out of working memory and whatever intermediate computation you are working out will suddenly "poof" out and disappear. Basically, your brain throws an OOM error, killing the current process.

One approach is simply to increase the context length, as they did to millions in Gemini [8]. Such a long context allows you to dump entire codebases, books, or multiple retrieved documents and look up very specific localized information from there. This is called "text needle in a haystack".

Increasing the attention context to ludicrous lengths requires a lot of care. A promising approach is ring attention [9, 10], where the input sequence is chunked into blocks and each block is sent to a device. Each device computes one transformer block on its local queries. Devices are connected in a ring, and the key-values are efficiently sent around in a way that overlaps with the computation. Another great method is Infini-attention [11]. Here the idea is that we break the sequence into blocks and propagate a compressive memory across all blocks, similar to an RNN. In each transformer block, based on the local Q, K, V, we retrieve some values from the compressive memory, add new values to it, and combine the retrieved values with the local attention values.

Here \(s\) is the block index, \(M_s\) is the compressive memory state, \(A_{\text{mem}}\) is the attention which has been retrieved from the memory, \(A_{\text{dot}}\) is the current multi-head dot product attention, and \(\sigma(\cdot)\) is some non-linearity. Overall, Infini-attention is recent, but has gathered strong attention.

Actions

Tools. Here the idea is to allow LLMs to use tools and a core method is Toolformer [12]. We give the model access to a limited number of APIs and train the model to annotate a bunch of text with those API calls that when executed, would solve a given task. This requires actual finetuning as the LLM has to recognize the tool for the job and extract the arguments for the API. It is also possible to provide a description of the available tools inside the prompt and rely on in-context learning, but this is much more brittle.

HuggingGPT [13] is an ambition project where a LLM is able to select and call all kinds of HuggingFace models on demand, from detection to generation... The role of the LLM is to plan the API calls and their inputs, and then aggregate the results into a coherent answer for the user.

Very exciting cases arise when we allow LLMs to interact with custom tools, like user-defined functions. Clearly, this has tremendous value as it allows LLMs to be integrated into personal projects and workflows. Frameworks like LlamaIndex, LangChain, or OpenAI's function calling make it very easy to setup functioning capable agents that can call custom functions.

Planning

Planning refers to any kind of procedure which refines the output instead of simply generating it and directly returning it to the user. This is a huge area. Let's explore the prompting toolbox.

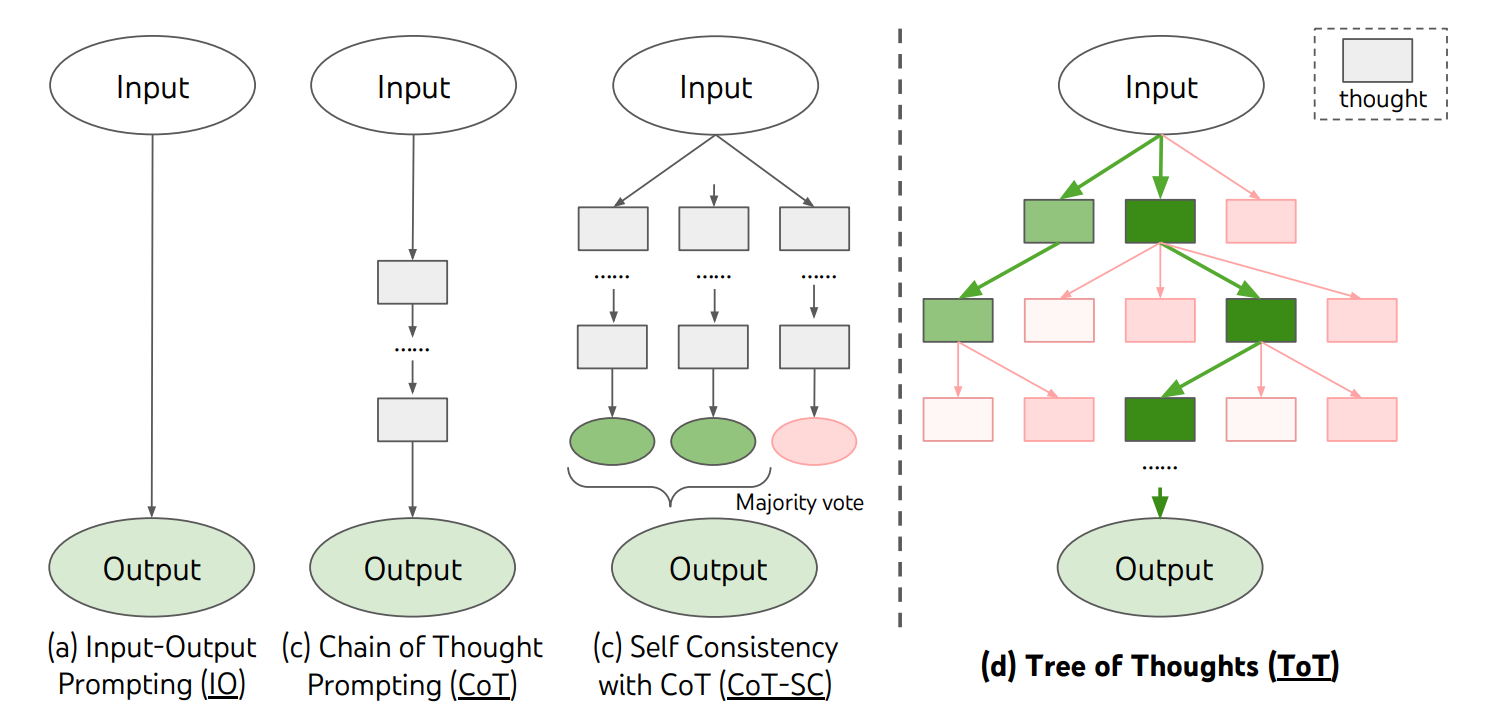

- Chain of Thought [14] argues that when providing the model with an example in the prompt, breaking it down into substeps and explaining how they connect to the final solution imroves performance. Also, asking the model to think "step by step" usually improves results.

- Self-consistency [15] samples multiple responses from the model and then chooses the most consistent one, essentially by doing a majority vote on them.

- Tree of Thoughts [16] takes a problem which is broken down (perhaps manually) into intermediate problems and then builds a solution tree. In each node the LLM is asked to produce a next partial solution to the problem and evaluate whether the problem is solvable with this proposed partial solution. If it's not, there's no point in searching in the corresponding branch of the tree. A usual BFS/DFS search is employed otherwise.

- ReAct [17] uses a reasoning-action-observation loop that is prompted, which is useful for learning how to reason over tool use.

- Self-Critique [18] prompts the model to criticise its generated response. This feedback is then added to the prompt and a new, improved response is produced.

- Reflexion [19] prompts the model to produce an action, executes it in the environment, and combines the environment reward with its own evaluation of the next state or trajectory. In this way it utilizes both internal and external feedback, before applying self-reflection to refine the action. It yield big performance gains in the tool-use tasks.

Thus, we see there's significant diversity in planning approaches. Despite the great results, these methods have been employed only on selected, isolated, perhaps artificial tasks. Some of them, such as Tree of Thoughts, still rely on humans breaking down the problem manually before giving it to the LLM. In general, it'd be best if all agentic components are finetuned jointly, but this is difficult due to the integration complexity and there's no convincing progress so far in that regard. Naturally, it takes lots of experiments to converge on the best way to do these things.

A Possible Breakthrough

Recently OpenAI released o1, the first of a new kind of reasoning agents. It achieves remarkable results, being able to solve PhD level chemistry, biology, and physics questions. It also places among the top 500 students in the US in a qualifier for the USA Math Olympiad. In IOI 2024 under the same constraints as human participants, it placed in the 49th percentile. Yet, with more available submissions it placed above the gold medal threshold. In a CodeForces example, it placed in the 93rd percentile. This is more than exciting.

At this time we don't know much about how it works. All we know is that it has been trained using chain-of-though (CoT) reinforcement learning to be able to break down problems, evaluate its output, expand on promising directions, and backtrack if a current approach is not working. Likely a search tree is built under the hood, similar to methods like MuZero or AlphaProof. There are novel scaling laws delineating how accuracy depends on the compute at test time.

Likely, a large part of the results can be explained by the size and quality of the training data, which perhaps consists of human evaluators ranking different CoT transitions. At test time, a sufficient search budget is also critical. Interestingly, OpenAI hides the actual trace of thoughts from the users. They say that for maximum quality the trace has to be unaltered, so you can't train any policy compliance models on it. Unaltered also means possibly harmful or unaligned. It's up to the open source community to reproduce this kind of reasoning and make the trace available to the user, which will be useful. Exciting times ahead.

References

[1] Chen, D. Reading Wikipedia to answer open‐domain questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.00051 (2017).

[2] Sparck Jones, Karen. A statistical interpretation of term specificity and its application in retrieval. Journal of documentation 28.1 (1972): 11-21.

[3] Lee, Kenton, Ming-Wei Chang, and Kristina Toutanova. Latent retrieval for weakly supervised open domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00300 (2019).

[4] Lazaridou, Angeliki, et al. Internet-augmented language models through few-shot prompting for open-domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05115 (2022).

[5] Guu, Kelvin, et al. Retrieval augmented language model pre-training. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020.

[6] Shi, Weijia, et al. Replug: Retrieval-augmented black-box language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12652 (2023).

[7] Longpre, Shayne, et al. Entity-based knowledge conflicts in question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.05052 (2021).

[8] Reid, Machel, et al. Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.05530 (2024).

[9] Liu, Hao, Matei Zaharia, and Pieter Abbeel. Ring attention with blockwise transformers for near-infinite context. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.01889 (2023).

[10] Shyam, Vasudev, et al. Tree Attention: Topology-aware Decoding for Long-Context Attention on GPU clusters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04093 (2024).

[11] Munkhdalai, Tsendsuren, Manaal Faruqui, and Siddharth Gopal. Leave no context behind: Efficient infinite context transformers with infini-attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07143 (2024).

[12] Schick, Timo, et al. Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

[13] Shen, Yongliang, et al. Hugginggpt: Solving ai tasks with chatgpt and its friends in hugging face. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

[14] Wei, Jason, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 24824-24837.

[15] Wang, Xuezhi, et al. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11171 (2022).

[16] Yao, Shunyu, et al. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

[17] Yao, Shunyu, et al. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.03629 (2022).

[18] Madaan, Aman, et al. Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

[19] Shinn, Noah, et al. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).