Learning and Searching

Some ideas are stirring. A few days ago Ilya Sutskever said at Neurips, paraphrasing, that we are running out of high-quality human generated text data with which to train LLMs. As a result, the pre-training paradigm of scaling up model and dataset sizes cannot go on forever. Performance of pure LLMs seems to be plateauing. The scaling hypothesis says that given a suitable architecture, one that sufficiently mixes all the features together, it is only a matter of scaling up training data and model size in order to get arbitrarily good, even superhuman, performance. Is this the case? It's hard to say. But a more important question is: if accuracy plateaus, at what level will it do so? People who argue against the scaling hypothesis believe that intelligence depends on a critical highly-sought algorithm that we need to find. It may not be precisely an architecture, but it is a design that we are currently missing.

But here's the thing. In the long run it has been empirically shown that computation is the main driver behind a model's performance. Not any special algorithms or designs that bring problem-specific human knowledge into the model, just computation. That's the bitter lesson. And to quote Rich Sutton, Search and learning are the two most important classes of techniques for utilizing massive amounts of computation in AI research. They are the drivers of long term performance.

Learning is obviously needed, as it allows us to solve a new set of problems - those which are hard to verify. Suppose I give you an image of a dog and ask you if it's a Labrador. How would you verify your answer? It's unclear. If you can't even verify, is recognition NP-complete? It doesn't fit neatly into a well-defined complexity class. To verify a recognition problem, you have to rely on visual patterns learned from previous image-label captions. So learning can be considered fundamental.

What about search? Naturally, many computational tasks - e.g. travelling salesman, shortest path, knapsack, chess, Go, optimal policy - require searching. You can't get good performance unless you search. And in ML this often leads to test-time compute, the idea that you will perform additional computations at test time, in the form of search, to improve your estimate on this problem instance, all without changing the model's parameters learned at train time. MCTS and various kinds of LLM prompting are examples here. Note that this is not a new idea. People have been doing planning and test-time augmentations, which are different forms of the same approach, for a long time now.

In general, solving tasks using reasoning boils down to proposing full- or partial solutions and evaluating them. Thus, we need an actor and a critic. And we need both to be very accurate so that good solutions are generated and recognized at the same time. A common way to search is called searching against a verifier. The idea is quite simple: we generate a bunch of candidate partial answers and evaluate them using a verifier model. The full solution is then constructed from the partial candidates.

Consider the following special cases:

- A single reactive answer is produced. This is fast, often inaccurate, and doesn't need a verifier.

- Majority voting - the model generates multiple final answers and the most common one is selected. This is sometimes called self-consistency [1]. It works if you increase the number of generated answers sufficiently, but beyond a number performance saturates.

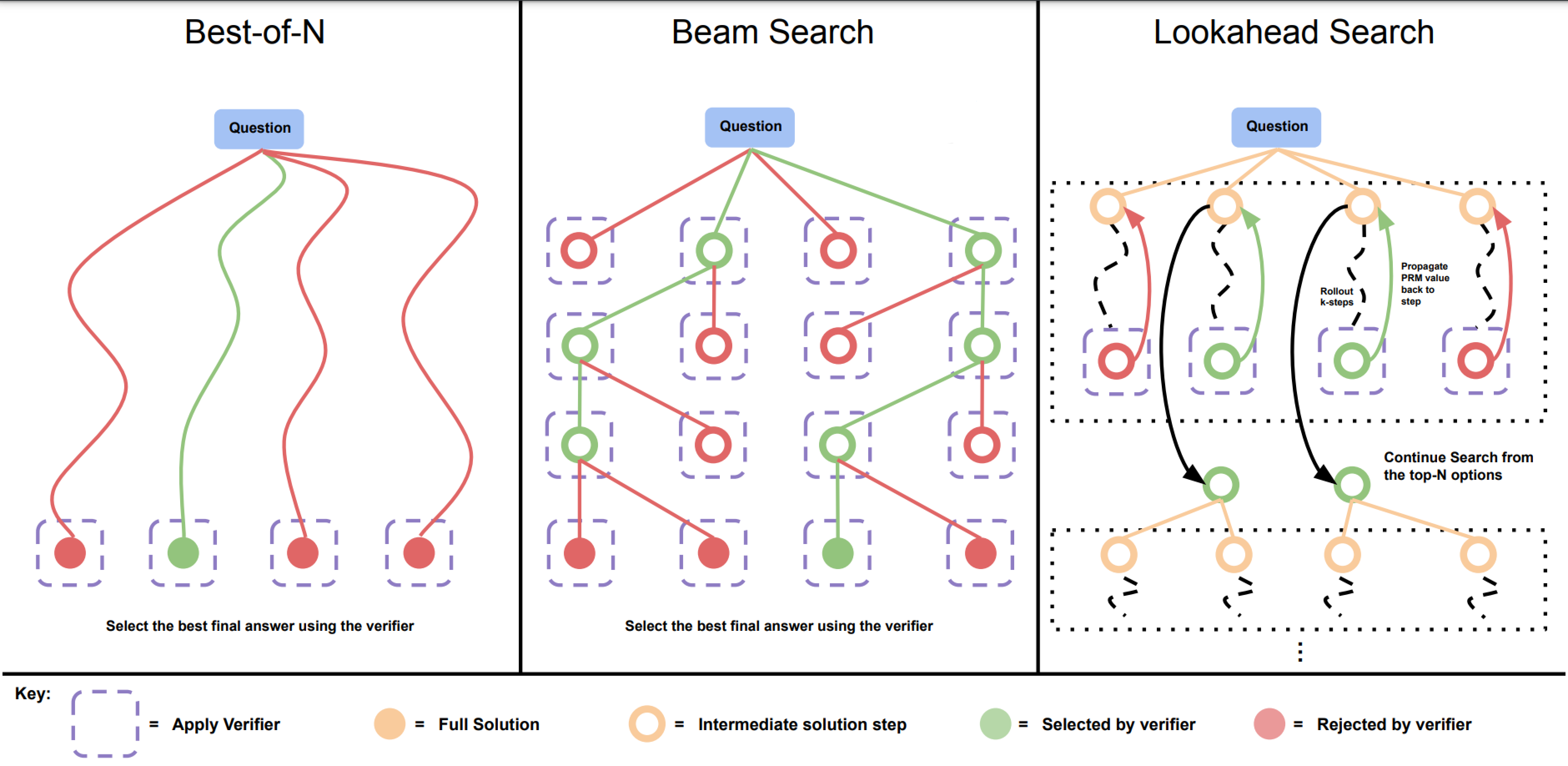

- Best-of-\(N\): Generate \(N\) complete answers, score them with a verifier and return the best one.

The verifier can score either a whole solution, in which case it's called an outcome reward model (ORM), or a partial one, which we call a process reward model (PRM). If we are constructing the solution iteratively, similar to chain-of-though [2], we needs to aggregate the rewards for one whole solution across all of its steps, typically by taking the minimum or the last reward. PRMs are trained on specific datasets where the solutions to various reasoning problems are broken down to individual steps, so that the model can learn which intermediate steps are good and which bad [3].

Beyond the best-of-\(N\) option, one can do beam search, a form of tree search, to iteratively build the final solution. This is very similar to how beam search can be used in the LLM inference process, where it works as follows:

- At the beginning, the model generates a distribution over its vocabulary, which is of size \(V\). We select the top \(k\) most likely next tokens and discard the rest. The selected tokens are stored along with their log probabilities, or in general their rewards, into a small datastructure representing the beam.

- At the next step, for each token in the beam we generate the next \(V\) candidates. Thus, there are \(kV\) total candidates.

- We compute all of their log probabilities, and again keep the top \(k\) tokens.

- Repeat steps 3-4 until a stopping criterion is reached, usually

[EOS]or maximum depth.

Keeping only the top \(k\) bounds the memory requirements while sacrificing completeness - the guarantee that the best solution will be found. Selecting the top \(k\) solutions at every \(n\)-th step is impractical as memory scales exponentially, as \(O(kV^n)\). Similar to how beam search is used for generation, it can be used for step-by-step reasoning. Here the model generates entire "partial solutions" and we keep only the top \(k\) at any time. Instead of the log probability, one uses the PRM. The model is purposefully instructed to think step-by-step and to delimit the individual parts of the solution, so they can be scored by the reward model.

Now, turns out there is no search method that performs best across all problems. Accoding to Google's large scale experiments [4], beam search tends to perform best on more difficult problem, while best-of-\(N\) performs best on simple ones. Thus, if one can predict problem difficulty beforehand, it would be possible to select the best search strategy given a fixed compute budget. This is called a test-time compute optimal scaling strategy and Google have shown that adopting it can decrease compute by a solid factor compared to baselines like best-of-\(N\) while holding performance fixed. Importantly, for certain easy and medium difficulty questions, test-time compute can easily make up for a lack of pretraining. On the contrary, for very difficult or specific questions where specific knowledge is required, pretraining will be more useful.

On the hardest problems, allocating more compute at test time is not worth it because, often, both the policy and the critic are too unreliable - the model neither proposes good actions, nor recognizes them. Instead, it should be obvious that in more constrained systems, where one of these components is near-optimal, we should be able to get top, even superhuman performance. Consider the following:

- AlphaGo [5], which beat Lee Sedol, the world champion at the game Go. Here both a policy and a learned value function are used. However, since they are used within the context of a Go simulator, the exactness of its nature provides very specific information in terms of which sequences of moves lead to a win. Thus, it is an example of a setting where the verifier can be trained with very accurate labels. Additionally, within the constraints of the simulator, by playing against lagged version of itself, the agent can in principle improve ad infinitum, far beyond human performance.

- AlphaGeometry [6], which solves olympiad-level geometry problems, uses a symbolic engine to assess geometric proofs and a LLM to suggest new geometric constructions. The symbolic engine is faultless and represents an ideal critic guiding the search by telling you precisely whether a new construction works or not.

- Beyond geometry, AlphaProof [7] similarly uses an automated proof system, Lean, which provides accurate fast answers of whether a theorem follows or not, or is uncertain from the premises. A Gemini LLM is trained to translate natural language problem settings into formal statements to build a big database of known lemmas. To prove or disprove a statement, a solver network searches its generations according to the proof system.

- Generally, tools can be considered precise verifiers that can guide the search. Having access to a REPL or to a compiler where the agent can score its predictions is what is needed for programming. Similarly, using solvers like Gurobi can be useful for dealing with constrained optimization problems. For other domains, e.g. vision and robotics, high quality photorealistic simulators are available, but we are yet to find out if they can be used as accurate verifiers when perception and planning-based reasoning tasks.

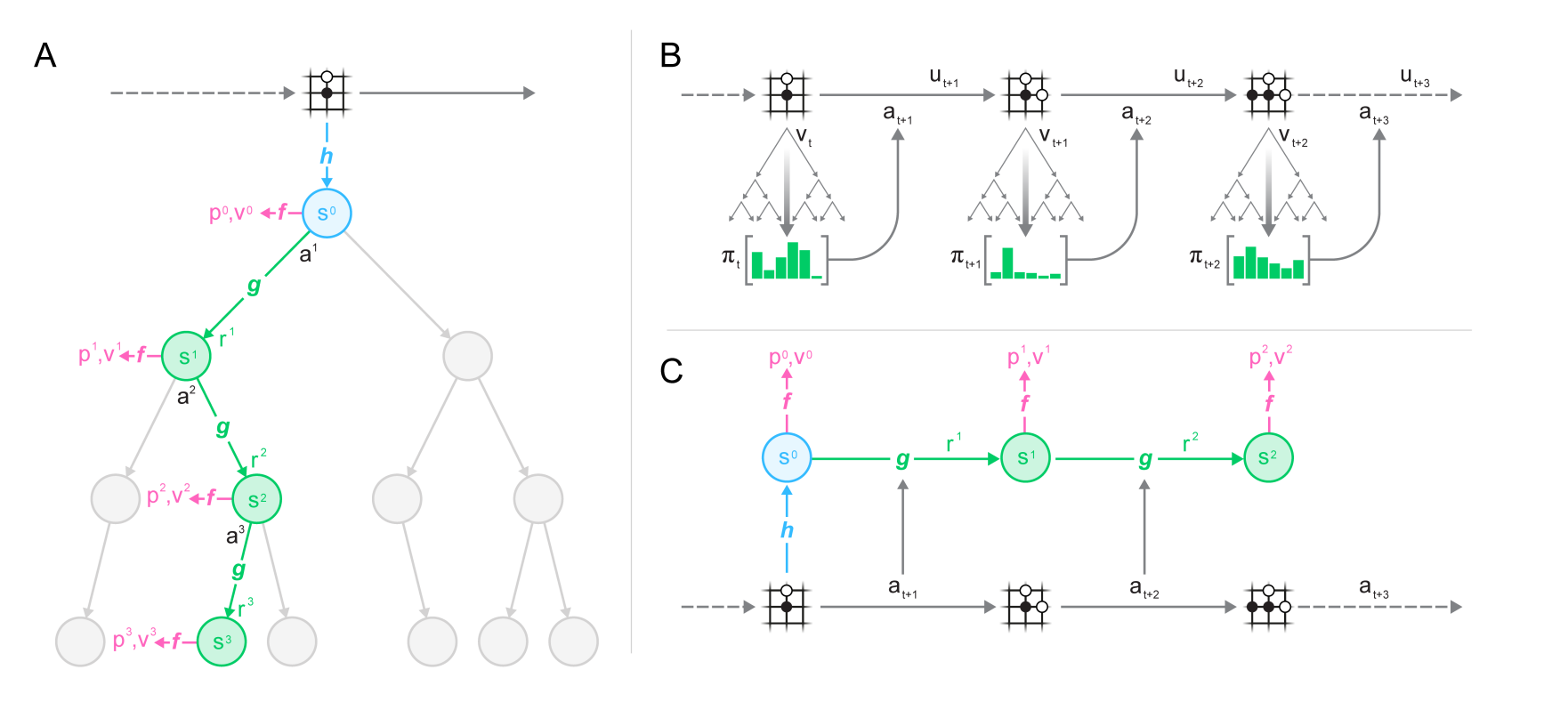

Let's take a closer look at Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), the search strategy for discrete actions in models like AlphaGo. To start, consider a Node structure which represents an environment state, along with various information like visit count, prior probability of reaching that state, value, etc. The agent actions are edges to next nodes and form a tree representing the possible game progress. To take an action using MCTS, the agent performs the following:

- Initialize a new root

Noderepresenting the current state. - Expand it. Use the policy and the value function to obtain action probabilities and the current state value. This creates children nodes.

- Perform tree search for a fixed number of iterations. For every single iteration do:

- Selection. Traverse the tree until a leaf node is found. To decide which child node to follow, use an uncertainty measure like the upper confidence bound (UCB), which trades-off exploration and exploitation. In the end, a leaf node is selected.

- Expansion. The selected leaf node could be a leaf either because it represents the end of the simulated trajectory, or because it has not been expanded so far. In the latter case, expand it by adding additional children as above, using the policy and value function.

- Simulation. Perform a roll-out from the newly added leaf using uniformly random actions until the trajectory ends. Here, if one uses a learned value function they can skip the simulation and simply use the boostrapped predicted value for that leaf as the value of the final node. Otherwise, one needs to simulate to get rewards.

- Backpropagation. Update the tree node parameters recursively from the final node to the root, along those nodes which have been visited during the rollout. Specifically, we trace the nodes by following the parent pointers, incrementing their visit counts, and summing up their values. Discounting by \(\gamma\) is not necessary due to the fixed simulation horizon.

- Finally, back at the root, select an action according to the visit counts of the root's children nodes. One can be greedy, selecting the argmax, or compute action probabilities and sample.

That is how action selection works. When the agent is playing against itself, the leaf values are additionally flipped in sign alternatingly during the backpropagation in order to represent the agent controlling both players. Moreover, note that the environment is used to simulate the new state whenever we traverse the game tree. In that sense, AlphaGo requires known rules.

One of the most beautiful model sequences follows from here. AlphaGo [5] achieved effectively superhuman performance on Go using known rules and some hand-crafted features (counting liberties, recognizing ladders). It was trained in a supervised manner on human expert actions and then with RL from self-play. AlphaGo Zero [8] improved over this by using only self-play, with zero human data and hand-crafter features. Subsequently, AlphaZero [9] learned to play not only Go, but also Chess and Shogi, all using the same tabula rasa approach. Finally, MuZero [10] entirely removed the reliance on the known rules. It did so by adopting dynamics predictors for the reward and the next latent state and then doing MCTS in the space of latent predictions.

Evidently, learning and searching has a lot to offer. This has already been shown in constrained settings such as board games and currently by combining LLMs with searching, this approach is slowly invading the generic language domains where broad reasoning is applicable. The performance of OpenAI's new o3 model has definitely shaken things up with enthusiasm, especially on benchmarks like ARC-AGI and FrontierMath. I'm looking at the future with great excitement.

References

[1] Wang, Xuezhi, et al. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11171 (2022).

[2] Wei, Jason, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 24824-24837.

[3] Lightman, Hunter, et al. Let's verify step by step. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.20050 (2023).

[4] Snell, Charlie, et al. Scaling llm test-time compute optimally can be more effective than scaling model parameters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.03314 (2024).

[5] Silver, David, et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529.7587 (2016): 484-489.

[6] Trinh, Trieu H., et al. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 625.7995 (2024): 476-482.

[7] AlphaProof and AlphaGeometry Teams AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems. (2024).

[8] Silver, David, et al. Mastering the game of go without human knowledge. Nature 550.7676 (2017): 354-359.

[9] Silver, David, et al. A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play. Science 362.6419 (2018): 1140-1144.

[10] Schrittwieser, Julian, et al. Mastering atari, go, chess and shogi by planning with a learned model. Nature 588.7839 (2020): 604-609.