Keynesian and Classical Econ

I've decided to better understand the Keynesian and classical macroeconomic views. This post covers both approaches in the short and long run. There will be some overlap with the previous article, but the emphasis here will be slightly different. Note that what we call here long run is actually the medium run in that post. The very long run, when output is determined by technological progress and capital, will not be considered here.

Aggregate output \(Y\) depends on the firms producing goods. In a closed economy, total output equal total income. The production function depends on capital \(K\) and labour \(L\), which are called the factors of production, and their costs are the rental price \(R\) and wages \(W\). Total output is determined by production.

Production. If firms are price-takers in both the inputs and output markets, as in perfect competition, then the price \(P\), wages \(W\) and rental costs \(R\) are exogeneous. Firms maximize profit \(\pi = PF(K, L) - RK - WL\) and a first-order condition for selecting the right quantity of \((K, L)\) is given by \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial K} = R/P\) and \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial L} = W/P\). Thus, it is optimal for firms to increase \(K\) and \(L\) until their marginal products become equal to the real costs of the factors of production - the real wage \(W/P\) and the real cost of capital \(R/P\).

Economic profits. Firm profits at that quantity equal \(\pi = Y - F_K'K - F_L' L\), where \(F_K'\) and \(F_L'\) are the corresponding derivatives. If we assume that the production function \(F\) has constant returns to scale, so that \(zY = F(zK, zL)\), and take the derivative with respect to \(z\) we get \(Y = zF_K' K + zF_L' L\). Setting \(z=1\) we get the exact expression for the profits \(\pi\). Thus, under perfect competition and constant returns to scale we can say that total income gets fully spent and divided between the factors of production, according to their productivities. There is no economic profit. An additional worker is employed only if his incremental contribution to profit is greater than his real wage.

Demand for goods and services. The total demand for goods and services \(Z\) comes from households, which consume (and save), firms, which invest (and produce), and governments which fund public projects (and tax), \(Z = C + I + G\). In an open economy the net trade balance also affects demand, but we'll assume a closed economy for now. Households spend a fraction of their disposable income \(Y - T\), with \(T\) being the taxes, in the goods and services markets. Whatever is not spent, is saved. These savings are deposited in banks or used to buy bonds, stocks, or mutual funds. In other words, savings enter the financial markets. Firms on the other hand invest in capital goods to increase their productive capacity. These purchases are funded by bank loans, or by issuing bonds and shares. Thus, a market for loanable funds is formed where households are the suppliers and firms are the consumers. Capital accumulation is an intertemporal affair and the price in the market of loanable funds is the interest rate. Thus, demand for inverstment depends negatively on the real interest rate \(r\), \(I(r)\).

Investment-Saving. For markets to clear, we need the supply for goods and services \(Y\) to equal the demand \(Z\). Note that at equilibrium, when \(Y = C + I + G\), one can rearrange the variables so that total spending, given by the sum of private spending \(Y - T - C\) and public spending \(T - G\) is equal to investment \(I\), i.e \((Y - T -C) + (T - G) = I\). This is the same way to look at the equilibrium - households' desire to save balances out firms' desire to invest.

Classical view equilibrium. The classical macroeconomic view is that the combination of \((K, L)\) is the only thing that determines output \(Y\). Hence, if the production factors \(K\) and \(L\) are fixed, then also total output \(Y\) is fixed. Government spending \(G\) is also usually assumed exogeneous and fixed. Hence, if there is a shock increase to, say, consumption, the only thing that can change is the real interest rate \(r\) in the financial markets. This is a crucial point. Demand-side shocks usually do not impact the production factors and hence output is unchanged. The variable which adjusts is the real interest rate \(r\). Hence the relationships:

- An increase in consumption \(C\) raises the interest rate as there are less loanable funds overall

- An increase in government spending \(G\) does not change consumption and output, but reduces equilibrium investment and increases the interest rate.

- Assuming consumption does not depend on the interest rate, an increase in investment demand raises the interest rate but not the equilibrium investment level.

Money. The classical quantity theory of money states that \(M \times V = P \times Y\). Here \(P \times Y\) is the nominal value of the output produced for a given period. \(M\) is the money supply and \(V\) is the money velocity (how many times a dollar bill enters someone's income in a given period of time). Intuitively, this identity says that to produce a value of \(PY\) we can use \(M\) units of money, each being used \(V\) times. Alternatively, one can use \(2M\) units, each being used \(V/2\) times. If we assume that the velocity is fixed, we get \(M \bar{V} = PY\), a proper theory claiming that whenever \(M\) increases, \(P\) increases proportionally, again, assuming a fixed \(Y\).

The implication is that the central bank, controlling \(M\), effectively controls the price level \(P\). Governments have benefits from printing money, thus even though the money supply affects only the nominal value of output, governments may not be indifferent to how much the money supply is. Generally, money demand is given in real terms as \(M^d/P = L(i, Y)\), increasing in \(Y\) and decreasing in \(i\). If we further assume that \(M^d/P = kY L(i)\), we get at equilibrium \(M^s/P = M^d/P = k YL(i)\) or \(M^s/k = PYL(i)\) which shows that for a fixed \(i\), the money velocity is \(1/k\).

Classical dichotomy. Note how in classical theory changes in the money supply do not influence any real variables. Money supply affects inflation and the price level, but not output, consumption, investment. This irrelevance of money for real variables is called monetary neutrality and is generally considered correct in the long run. Thus, in the classical view, inflation is caused by an increase in money supply. Shocks to demand are met by a reaction of the real interest rate. Income is determined by production. It is common to think of the long run in this way.

Nominal rigidity. Many people believe that prices are not flexible in the short run, they are sticky. As a result, the economy's behaviour in the short run could be different from that in the long run. In fact, in the short run changes in the money supply for example could have real impact on output, i.e. output could turn out to be demand-driven.

Aggregate supply and demand. It is useful to look at the whole economy for goods and services as a single market governed by supply and demand. Naturally, the focus is on how the quantity supplied/demanded depends on the price level. From the quantity theory of money \(MV = PY\), assuming fixed \(M\) and \(V\), we get an inverse relationship between \(P\) and \(Y\), \(Y = \bar{M} \bar{V} / P\). This is basically aggregate demand, downward sloping and all.

Aggregate supply is a bit tricky. In the long run output does not depend on the price, just on the factors of production. Hence, in the long run, if plotted with \(P\) on the \(y\)-axis and \(Q\) on the \(x\)-axis, aggregate supply is vertical. Output is at \(Y(\bar{K}, \bar{L})\). If the central bank increases \(M\) and we assume that prices can change, then \(P\) increases to counterbalance an increase in \(Y\), which stays the same. In the short run prices are fixed, irrespective of \(Y\), hence aggregate supply is a horizontal line. An increase in \(M\) increases the aggregate demand and the economy transitions to a new short run equilibrium state with the same \(P\) but larger real \(Y\).

Consider what happens if the money supply decreases. In the short run, this causes aggregate demand to become lower. Short run aggregate supply is fixed. The short run equilibrium has lower output \(Y\) and the same prices \(P\). As prices start to adjust and to fall, the aggregate demand increases, bringing the economy back to the long-run equilibrium, where output is at its potential level. The corresponding rate of unemployment is the natural rate of unemployment.

Keynesian cross. The IS-LM can be used as another model for aggregate demand. Let's see what's going on there. Demand for goods and services is \(Z = C + I + G\), which is basically the planned expenditure for the year. The actual expenditure is given by the actual output, or income, \(Y\). In a standard Keynesian cross formulation, to have equilibrium we need planned expenditure to equal actual expenditure, so we need \(Y = C + I + G\). But how does \(Y\) adjust? Here it gets a bit sketchy. Firms usually adjust \(Y\) by changing \(K\) and \(L\). Here, however, \(Y\) adjusts without changes in those variables. This happens through firms' inventory management. We assume that firms hold inventories which act as a buffer and increase whenever demand is less than supply, and decrease otherwise. Intuitively, we can think of a factory that temporarily increases the working hours of its employees to meet a tight demand schedule, without hiring new employees or paying them additional wages. Such inventory adjustments are only possible in the short run, before prices have had time to adjust. So, solving for \(Y = C + I(r) + G\), we obtain the output \(Y\) as a function of the interest rate \(r\).

Liquidity preferences. Yet, in the money market, we have people's liquidity-preferences according to which the interest rate adjusts to equilibrate the supply and demand for real money balances. From the central bank's supply of money \(M^s/P\) and the real demand \(M^d/P = Y L(i)\), we find how the equilibrium \(i\) depends on \(Y\), which is called the LM curve. By intersecting it with the IS curve (the solution to the goods markets) we get the short-run general equilibrium. Note that in the IS relation the interest rate is real, \(r\), whereas in the LM relation it's nominal. This is not a problem since they are related.

Finally, to derive the aggregate demand (AD) curve we simply track \(Y^\ast\), as determined from the IS-LM model, as we trace \(P\). Shocks to consumption, investment, or government spending shift the IS curve and hence shift the AD curve. Similar for shocks that affect the LM curve.

We can think of the IS-LM equations as two equations for determining three variables, \((Y, r, P)\). We need a third equation in order to uniquely determine the variables. The Keynesian view for the third equation is that \(P = \bar{P}\), which is saying that prices are sticky. The classical view for the third equation is that \(Y = Y_n\), i.e. that the output tends to its natural level. Which of these is correct? The common view is that the Keynesian one is correct in the short run, while the classical one is correct in the long run.

Aggregate supply. How does aggregate supply look like? Like most supply functions it is upward sloping. One possible derivation is as follows. Assume in the labour markets firms wages are determined as \(W = P^e f(u, z)\) where \(W\) is decreasing in the unemployment rate and increasing in the catch-all variable \(z\). Firms are price-setters and set prices according to some markup above the wages, \(P = (1 + \mu)W\). Combining these we get

The unemployment rate \(u\) is equal to \(u = 1 - N/L\) where \(N\) is the number of employed people and \(L\) is the labour force. As a huge approximation one can write \(Y = N\) which comes from looking only at the labour as a factor of production and normalizing the units of measurement such that \(Y = N\). With this, unemployment becomes \(u = 1 - Y/L\) and the aggregate supply is given by the following function, increasing in \(Y\):

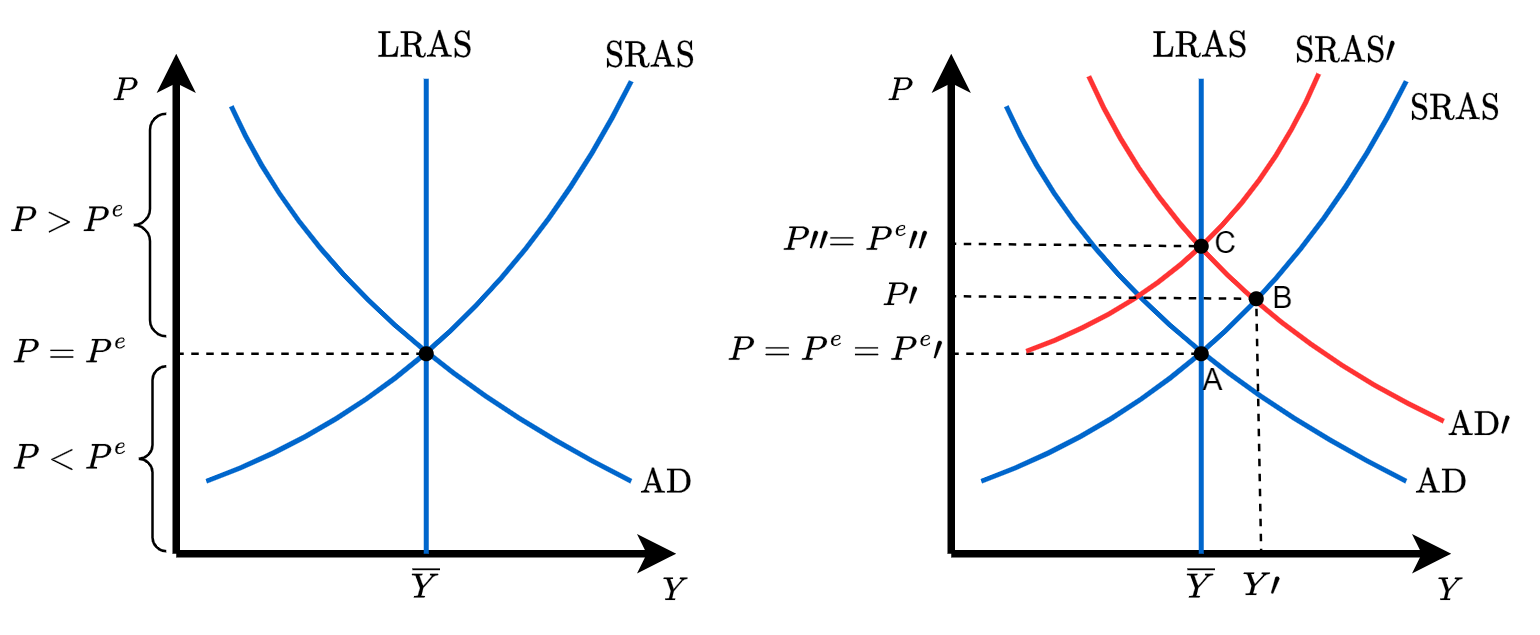

When prices are equal to expected prices, \(P = P^e\), we can simplify and solve for \(u_n\) and \(\bar{Y}\), the natural rate of unemployment and potential output. The equation can be further sumplified, using a linear functional form for \(f\) and various approximations, to get \(P - P^e = \alpha(Y - \bar{Y})\), which is the canonical form of the aggregate supply. Since here firms are price-setters, causality goes as follows: an increase in \(Y\) leads to a decrease in \(u\), which through the wage-setting relation leads to an increase in \(W\) which leads to an increase in \(P\).

To recap, the short-run AS has the following characteristics:

- At low \(Y\) and high unemployment, such as in a recession, firms can produce more to meet increased demand without raising prices. This happens by relying on their inventories and better utilizing their capital such as plants and factories. Because of the overall abundance of available workers, firms don't have to bid wages up in order to hire. Since costs do not increase, prices also stay fixed. AS is horizontal or barely increasing.

- If \(Y > \bar{Y}\) and unemployment \(u < u_n\), the production costs increase in \(Y\). Workers are relatively scarce which means they can demand higher wages. To produce more, firms hire more workers and pay higher wages, which in turn raises overall prices, resulting in inflation.

From short-run to long-run. How does the economy transition from the short-run to the long-run? Figure 1 plots the transition visually. Suppose we start at long-run equilibrium, potential output \(\bar{Y}\), natural rate of unemployment \(u_n\) and prices being equal to expected prices - point A. Now, a shock to aggregate demand, perhaps by increased government spending shifts AD to the right. To respond to the increased demand, firms rely on inventories and labour to temporarily increase output to \(Y'\). This increase is demand-driven. Since we already start from full employment, firms compete for scarce workers by bidding up wages, which in turn raises prices, leading to equilibrium point B, where prices are higher. In the long run, price expectations eventually adjust. This shifts the AS curve further up and the economy moves from point B to point C.

These are roughly the dynamics that occur when a short-run shock moves the economy beyond its potential output, which causes inflation to increase and unemployment to decrease below its natural level. In the long-run output returns to its potential level, while prices are higher.