Some Deep Learning Optimizers

Gradient descent is by far the most dominant optimization algorithm in AI. It has proven itself capable of training even the biggest and baddest models out there - multi-billion parameter LLMs, small networks with complicated forward passes, and anything in between. It's the best optimization algorithm we have right now. It's not very biologically realistic, but it compensates by being able to train those models which can simulate biological realism. And the idea of simply following the steepest direction is as beautiful as it gets. Here we'll explore some of the most widely used deep learning optimizers.

Gradient descent works by calculating the gradient (partial derivatives) of the loss function with respect to each parameter. The gradient gives the direction of the steepest increase in the function, and the algorithm updates the parameters by taking steps in the opposite direction of the gradient, which represents the steepest decrease in the function. This process is repeated iteratively until convergence is reached, such as when the absolute difference of the parameters from two sequential updates falls below some small value, or a stopping criterion is met, typically a maximum number of iterations.

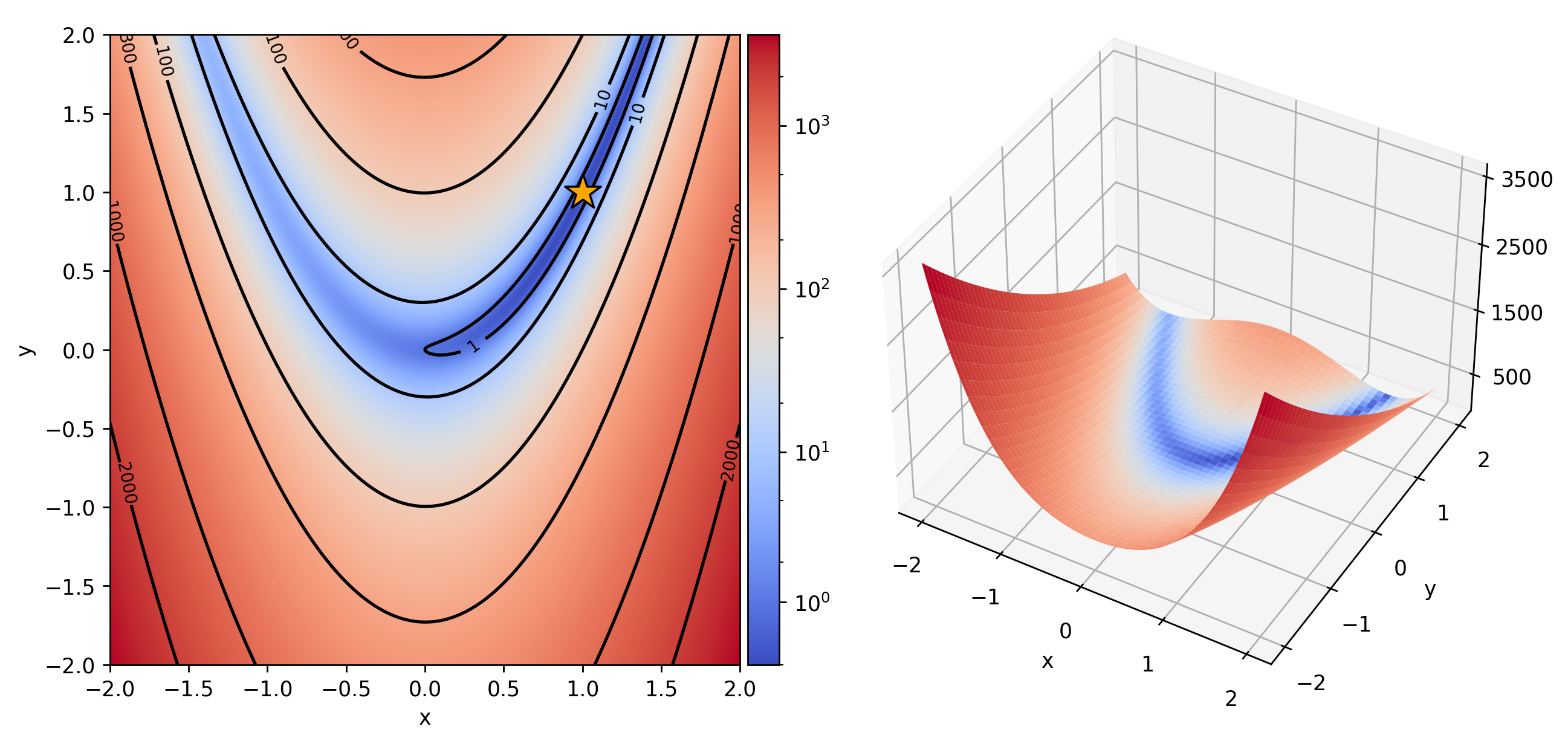

Consider the following two-dimensional Rosenbrock function which can be considered as a testing example:

It is common to set \(a=1\) and \(b=100\), after which the single global minimum is found at \((1, 1)\). The contour plot is shown in Figure 1. This function is useful for testing optimization algorithms because the global minimum is found in a very flat and long valley. Reaching this valley, but moving along it is difficult because the gradient is very weak there.

Gradient descent. Let's rename \((x, y)\) with \(\theta = (\theta_1, \theta_2)\) to better indicate that \((x, y)\) are the parameters \(\theta\) that we are optimizing over. We write the gradient evaluated at \(\theta_t\) as \(\nabla_\theta F(\theta_t)\). Then, standard gradient descent updates \(\theta\) by taking a small step in the direction of the negative gradient:

Here \(\theta_t\) are the parameters at iteration \(t\), which for the Rosenbrock function includes both \(x\) and \(y\). We can refer to them individually using the notation \(\theta_{t, i}\) where \(i \in \{ 1, 2 \}\). \(\eta\) is the learning rate, also called the step size, and contributes to how big the change in the parameters is. The other thing which determines the change is the gradient \(\nabla_\theta F(\theta_t)\) which causes large updates in regions where the loss landscape is steep and small updates otherwise. If the learning rate is sufficiently small, following the negative gradient will eventually converge to a local minimum. If the learning rate is large, the parameters may diverge to infinity or may start oscillating in a limit cycle.

In standard gradient descent the learning rate is constant both across iterations \(t\) and across individual parameters \(i\). This setup is very simple but unfortunately has significant drawbacks. For functions which are steep along one direction, but flat along another, gradient descent will typically lead to very slow movement along the flat direction. This is the case with the Rosenbrock function. Our estimates reach the valley within just a few steps but after that the updates become tiny. Mathematically, the Hessian, the matrix of second derivatives, which shows the curvature in the neighborhood of the current point, has very different eigenvalues. One of them is very small, showing that the curvature of the loss landscape changes very slowly along the first eigenvector, in the direction of the minimum. And the other eigenvalue is very large (even hundreds of times larger), showing that the curvature changes rapidly in the transverse direction, along its corresponding eigenvector.

Adagrad. From this it seems that we need a method which can adapt the individual learning rate depending on the parameter. Adagrad was the first to propose such a modification [1].

Here the idea is to divide the learning rate \(\eta\) by a parameter - a time-dependent vector \(\sigma_{t}\) which scales the updates applied to each individual parameter. Note that \(\sigma_t\) and \(g_t\) are vectors of size equal to the number of parameters. All operations are applied element-wise. We keep the cumulative sum of the squared derivative of each parameter as the number of iterations grows. Why? Because dividing by the magnitude of the gradient gives us a large learning rate in flat regions and a small learning rate in steep ones. The accumulation of the squared gradients smoothes out this effect. Note that this accumulation never decreases. As a result, we get an automatic learning rate scheduler that decreases the updates in a monotone way. This can be addressed by changing it to the average, in which case the learning rate is reduced only when the current gradient is larger than the average past gradient.

Empirically, it has been noted that Adagrad works particularly well for problems where there are sparse gradients. For parameters whose gradient is large or dense (frequently non-zero) the sum will increase fast and hence the learning rate for that parameter, after dividing by the square root of the cumulative sum, will be decreased. On the other hand, for parameters whose gradients are sparse (contain mostly zeros), the cumulative sum will increase slower, and hence the learning rate will be larger. Sparse gradients typically occur when the inputs are sparse, when we are using sparsity-inducing activations or losses, or when the outputs are sparse.

RMSProp. That being said, one problem is that in a non-convex function the learning rate may decay too rapidly due to the accumulation of the gradients. If we are in one basin of attraction in the loss landscape, it is reasonable to want to forget the gradients collected from different regions. One improvement proposed in 2012, is Hinton's Root Mean Squared Propogation (RMSProp) optimizer:

In this variation the vector \(\sigma_{t}\) is updated using a weighted average of the past learning rate modifiers \(\sigma_{t-1}\) and the current gradient \(g_{t}\), i.e. \(\sigma_{t} = \sqrt{\alpha \sigma_{t-1}^2 + (1 - \alpha) g_t^2}\). Since \(\alpha \in (0,1)\), the weighted average ensures that some part of the previous gradients is forgotten, which also prevents the fast learning rate decay problem that Adagrad has.

Consider what happens with RMSProp when we enter the flat valley in our test function. At some point, when the previous gradients outside of the valley are forgotten, the current gradients will be \(g_{t} = (a, b)\) and the previous sigma will be \(\sigma_{t-1} = (| a |, |b |)\). Then, as a result, the current sigma will be \(\sigma_{t} = (|a|, |b|)\) and the update will be \(-\eta (a, b)/(|a|, |b|) = -\eta (\text{sgn}(a), \text{sgn}(b))\). If the valley is symmetric in the direction perpendicular to the gradient, it may happen that at the next iteration the update is the same, except the signs will be reversed. This causes oscillation in the parameter trajectory. The parameters will still move in the right direction, but they will oscillate from side to side, reducing the rate of convergence.

Stochastic Gradient Descent. Virtually all problems that are encountered in deep learning have a loss function that is a sum or mean across many samples. This is completely different from our Rosenbrock test function where there is no data \(x_i\), only parameters to estimate. In deep learning the simplest loss function is the squared loss between the ground truth label for sample \(i\), \(y_i\), and the prediction \(\hat{y}(x_i, \theta)\) that depends on the parameters \(\theta\):

We're trying to find the parameters \(\theta\) such that the average squared error between our predictions \(\hat{y}(\theta, x_i)\) and the labels \(y_i\) is minimal. Gradient descent, obviously, requires us to compute the gradient of the loss function in order to do a single step. But here the gradient is given by

which contains a sum over all the samples in the dataset. Clearly, if the dataset is large, this sum will be too slow and expensive to compute. Instead what we can do is compute the gradient over a much smaller, random subset, or minibatch of the data samples. Since the samples are random, the gradient will be random as well. For that reason, gradient descent on small random subsets of the data is called stochastic gradient descent.

This is one of the hidden wonders of deep learning. The stochasticity actually helps with generalization, as the random movements introduced by it help to jump out of the basins of attraction of bad local minima. It's very hard to quantify this effect, but it's very easy to see it in practice. The batch size, or technically the size of the minibatch, is the parameter controlling how much stochasticity is introduced in the training and subsequently how likely it is that we jump around the true gradient, instead of following it. All else being equal, a larger batch size leads to less noise in the gradients, less generalization capability, but faster training. Finally, when increasing the batch size by a factor of \(k\), it is advisable to increase the learning rate by a factor of \(\sqrt{k}\), so as to keep the variance of the step size the same.

Momentum. A separate improvement which is somewhat orthogonal to the discussion of the adaptive learning rate to different parameters is that of momentum, also known as the heavy ball method, by analogy with a ball which accelerates when it rolls downhill. The idea is that the parameters will now have a kind of velocity \(\Delta \theta_t = \theta_t - \theta_{t-1}\), dampened by a parameter \(0 < \alpha < 1\), which also acts as an exponential decay when it comes to forgetting previous velocities. The update is given by:

In practice, momentum can speed up convergence significantly. In cases where the gradient is first steep and then flattens out, like in the Rosenbrock function, the parameters will continue to update by a lot after entering the flat region, and thus will cover a lot of distance in just a few steps. Of course, if the loss landscape is highly non-convex or jagged having too much momentum can cause the parameters to overshoot, similar to having a learning rate which is too large.

A further improvement is what's called Nesterov momentum. Here the entire update consists of two parts: first we make a big jump using the momentum \(\alpha v_t\) and then perform a correction in the direction of the gradient \(-\eta \nabla_\theta F(\theta_t + \alpha v_t)\) evaluated at the new location. Summing these two terms yields the full update:

Applying the gradient step after the momentum step acts as a kind of lookahead and works very well in practice. However, computing the gradient in a shifted position is a bit inconvenient. We can reparametrize in the following way. Let \(u_t = \theta_t + \alpha v_t\). Then \(u_t - \alpha v_t = \theta_t\) and \(u_t - \alpha v_t + v_{t+1} = \theta_t + v_{t+1} = \theta_t + \alpha v_t - \eta \nabla_\theta F(u_t) = \theta_{t+1} = u_{t+1} - \alpha v_{t+1}\). After some simplification we get

At this point \(u_t\) can be simply renamed to \(\theta_t\) again and we now have a version of the Nesterov momentum that does not require computing a shifted gradient. Compared to standard momentum, the Nesterov variant is can alleviate the overshooting that would result from setting the momentum parameter or the learning rate too large. By using information about the "future" gradient it can deal with oscillations somewhat better, converging faster to a minimum.

Adam. Combining adaptive gradients with momentum yields the most popular and widely used optimizer in AI right now - adaptive moment estimation, or Adam [2]. Here, we'll keep a running estimate for the first and the second moment for the derivative of every single parameter. The running estimates are updated using an exponential decay, similar to RMSProp - \(m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t\) for the first moment and \(v_t = \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) g_t^2\) for the second one.

The first thing to do is to unroll the estimates for \(m_t\) and \(g_t\) and obtain a closed form for them:

A similar expression holds also for \(v_t\). Now, it can happen, and most often does, that the gradients \(g_t\) are random. This occurs if one is using stochastic gradient descent or if the task itself is stochastic - for example optimizing the policy parameters of an agent operating in a stochastic environment. In that case we are interested in the expectation of our moments. If we assume that the gradients have a stationary distribution so that \(\mathbb{E}[g_{t-1}^2] = \mathbb{E}[g_{t-2}^2] = ... \mathbb{E}[g_0^2]\), then for the expectation of the exponential moving average we get:

It's clear that by dividing \(\hat{v}_t = v_t/(1 - \beta_2^t)\) is an unbiased estimator for \(g_t^2\). The analogously bias-corrected \(\hat{m_t} = m_t/(1 - \beta_1^t)\) acts as the momentum term which will add modify the behaviour of the parameters. Dividing the parameters by \(\sqrt{\hat{v_t}}\) ensures that in steep regions of the loss landscape the step size will be decreased. Adam is then given by:

In practice the default hyperparameter values are \(\beta_1 = 0.9\) and \(\beta_2 = 0.999\). \(\beta_1\) increases the effect that the acceleration from an initial steep gradient will have on the learning and it's a very useful parameter to tweak for loss landscapes which have wide flat regions. \(\beta_2\) roughly controls how fast the step sizes of individual parameters are scaled with respect to changes in the curvature of the loss landscape.

It is common to use regularization alongside the original objective function - for example weight decay \(\lambda {\lVert \theta_t \rVert}^2_2\). If we add the regularization term naively in the total loss function, then the regularization will enter the \(m_t\) and \(v_t\) terms and they will start interacting in strange ways. Instead, the gradient of the regularization term should be added separately as another additive component to the updates of \(\theta_t\) directly. This prompts the AdamW (adaptive moment estimation with weight decay) algorithm which is quite popular as well.

Radam. Let's do some quick statistical analysis on the properties of Adam. In what follows it's useful to know that if \(X \sim N(0, 1)\), then \(X^2\) has a Chi-squared distribution with \(1\) degree of freedom, \(X^2 \sim \chi^2(1)\). Similarly, \(1/X \sim \text{Inv}\)-\(\chi^2(1)\) - the inverse chi squared distribution.

Let's assume that the gradients have a normal distribution, i.e. \(g_1, g_2, ..., g_t \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\). Then the inverse square of each gradient comes from the scaled inverse chi squared distribution, which is quite similar to the standard inverse chi squared distribution, \(1/g_i^2 \sim \text{Scale-Inv}\)-\(\chi^2(1, 1/\sigma^2)\). And here is the problem, depending on some parameters, this distribution may have infinitely large variance. As a result, averaging the gradients may not really converge to the true gradients of the whole dataset and the steps we take initially may be in the wrong direction. We need to find a way to reduce the variance in the early stages of the training. This is the problem that the Radam optimizer tackles [3].

The adaptive learning rate in Adam comes from the \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{\hat{v_t}}}\) term. Let's denote the square root of its inverse with \(\psi(g_1, ..., g_t)\):

We can assume that this exponential moving average (EMA) is well approximated, at least early on, by a simple average (SMA). As a result, the distribution of the EMA will be approximately that of the SMA:

Since \(\frac{t}{\sum_{i=1}^t g_i^2} \sim \text{Scale-Inv}\)-\(\chi^2(t, 1/\sigma^2)\), we can also claim that \(\psi^2 \sim \text{Scale-Inv}\)-\(\chi^2(\rho, 1/\sigma^2)\), for some parameter \(\rho\). Now, the EMA is a good approximation of the SMA for some particular length \(f(t, \beta_2)\) that makes the SMA have the same "center of mass" as the EMA. The degrees of freedom \(\rho\) can be taken to be an estimate for the length \(f(t, \beta_2)\). We can find \(\rho\) as follows:

From now on, let's set \(r_\infty = \frac{2}{1 - \beta_2} - 1\) as it's the highest value that \(\rho_t\) can take. Now, it can be proved (here we take it for granted) that the variance of \(\psi\) is minimal when \(\rho_t = \rho_\infty\).

Since \(\psi^2\) is distributed as a scaled inverse chi-square, we can actually compute the variance of \(\psi\). To enforce consistent variance of \(\psi\) throughout the training, we can multiply \(\psi\) by some rectification term \(r_t\) such that \(\text{Var}(r_t \psi)\) is minimal - which occurs when \(\rho_t = \rho_\infty\). Skipping the derivation, we have

So here's how Radam works. We approximate the EMA for the second moment of the gradients with a sufficiently long SMA that has a familiar distribution. At the beginning, \(r_\infty\) is computed. Then, in step \(t\) of the optimization process, Radam computes \(\rho_t\) from which the variance of \(\psi\) can be determined. If it's tractable, we multiply the learning rate by \(r_t\) to obtain a small and consistent variance over the course of the training. If it's intractable, which happens when \(\beta_2 < 0.6\), tough luck.

It's worth mentioning that this kind of enhanced optimizers is not the only way to deal with large variance early on. One can also start updating the parameters after a number of steps, so that \(\psi\) has been computed from a sufficiently large number of samples. Additionally, one could adopt a warmup schedule on the learning rate, starting from a very small value and gradually increasing it to the desired level.

Lookahead. There is another line of work apart from adaptive learning rates and momentum which has become quite important recently. The idea is that one keeps two sets of weights - \(\theta_t\), called the "fast weights", which are updated frequently, and \(\phi_t\), called "slow weights", which are updated only periodically. The motivation here is that while using most SGD variants works well in practice, these methods may be quite sensitive to hyperparameters, especially on some datasets. By using two sets of weights, where the fast weights are used only as a form of lookahead, we essentially collect precious information about the loss landscape and then make a more informed decision by updating the slow weights [4].

Suppose the fast weights \(\theta_t\) are updated by any optimizer \(A\). Then at timestep \(t\), we first synchronize the fast weights with the slow weights from the previous iteration, then perform \(k\) steps with the inner optimizer - \(\theta_{t,i} = \theta_{t, i-1} + A(\mathcal{L}, \theta_{t, i-1}, d)\). Each of these updates is computed on a random minibatch of data \(d \sim \mathcal{D}\). After the \(k\) steps, we update the slow weights by linearly interpolating in the direction of \(\theta_{t,k} - \phi_{t-1}\) using a step size for the slow weights \(\alpha\):

By rolling out the recursive updates, we can see that the slow weights are updated in an exponentially moving average manner.

When analyzing the convergence rate of optimizers, one can assume the noisy quadratic model as a loss function - essentially a quadratic function \((x-c)^T A (x-c)\) where \(c\) is a random vector. Suppose in that context we compare Lookahead with SGD as the inner optimizer and plain SGD. The iterates of both algorithms would reach fixed points with expectation \(0\) but with different variances. It can be proved that the fixed point of the Lookahead method has strictly smaller variance than that of the fixed point of the SGD inner-loop optimizer for the same learning rate.

Ranger. We are slowly reaching state-of-the-art. FastAI's Ranger was for quite some time the fastest optimizer out there. And the idea behind it is more than straightforward - it is simply the combination of RadamW with Lookahead. RadamW itself is a variant Radam, where alongsite the rectification term, we have properly added weight decay regularization, similar to AdamW. By using RadamW as the inner-loop optimizer in Lookahead, the resulting optimization is made even more stable and robust to hyperparameter changes.

Layer-wise adaptive learning. Consider what happens if we use \(N\) GPUs instead of only \(1\) to train a network. What is typically done is to split the samples in the minibatch evenly across all computational units. Each unit computes the loss and the gradients over \(B/N\) samples, where \(B\) is the batch size and \(N\) is the number of GPUs. The gradients are then averaged across all GPUs and each copy of the model on every GPU is updated with the synchronized weights. Using many computational units allows us to process more samples in the same iteration, which is quite like increasing the batch size. But if the batch size increases by \(k\) times, then we'll perform \(k\) times fewer updates. So to keeps things similar, we should increase the learning rate by \(k\) times. Do you see where this leads? Increasing the number of computational units requires us to increase the learning rate, but increasing that too much can become quite unstable for training.

To get a sense of how stable an update is we can measure the ratio between the norm of the layer weights and the norm of the gradients, \(\lVert \theta^l\rVert / \lVert \nabla_{\theta^l} \mathcal{L}(\theta^l)\rVert\). If this ratio is too high, the training may become unstable. If it's too low, then the weights aren't updated fast enough. Moreover, this ratio typically varies wildly across the different layers in the network, which in turn motivates the need for individual per-layer learning rates. LARS was the first approach to do that [5].

In LARS (layer-wise adaptive rate scaling) we have a global learning rate \(\eta_t\) which depends only on the iteration \(t\). We also have per-layer learning rates \(\lambda_t^l\) which control the learning rates of each layer (not each individual weight):

Here \(\theta_t^l\) are the weights of layer \(l\) at time \(t\), \(\beta_1\) is a momentum term, \(\delta\) is a weight decay term, and \(g_t^l\) is, for lack of a better notation, the gradient at time \(t\) for layer \(l\). So LARS is essentially SGD with momentum, weight decay, and per-layer adaptive learning rates, given by \(\lambda^l_t\). This modification allows us to train large convolutional networks on many GPUs while still being able to afford a large global learning rate.

Nonetheless, it has been observed that LARS doesn't perform well on specific attention-based models. A straightforward improvement is LAMB [6] - the equivalent of LARS but with ADAM as the main optimizer. The idea is to compute the first and second moment estimates \(m_t\) and \(v_t\), bias-correct them, and calculate their ratio \(r_t = \hat{m}_t / \sqrt{\hat{v}_t}\), similar to Adam. Now the only change in \(\lambda_t^l\) becomes \(\lambda_t^l = \lVert \theta_t^l \rVert / (\lVert r_t^l \rVert + \lVert \delta \theta_t^l \rVert)\).

RangerLARS. The final optimizer we'll consider here is RangerLARS - the combination of Ranger and LARS. It's also called RangerLamb, or even Over9000. It has been benchmarked extensively on many different datasets and tasks and is probably the fastest optimizer that we have right now. The inner-loop optimizer consists of Radam and LARS/LAMB and works as follows. The Radam rectification \(r_t\) is computed and based on it we get the Radam step size \(- \eta_t r_t \hat{m}_t l_t\). Here \(\eta_t\) is the learning rate, \(\hat{m}_t\) is the bias-corrected first moment, and \(l_t = \sqrt{(1 - \beta_2^t)/v_t}\) is the adaptive modifier. Then comes the LARS part - we calculate the ratio of the norms \( \lambda_t = \lVert \theta_t \rVert / \lVert \eta_t r_t \hat{m}_t l_t \rVert\), multiply the radam step size with it, and update... and all this happens independently for each layer... And periodically update the slow weights using Lookahead.

In practice, there are a lot of tricky corner cases that need to be handled in the implementation. First the Radam step may not be applicable, in which case it has to be substituted with a simpler form that does not use variance rectification. Second, the gradient of the weight decay has to be accounted for. Third, what happens if \(\lVert w_t \rVert\) is very big? In practice, it's common to clamp it to \([0, 10]\). But even when RangerLARS does in 25 epochs what Ranger does in 120, there are very small rooms for improvement. Some people have noticed that the weights become rather noisy as the training continues. To mitigate this, the clamping process, given by the formula \(\text{max}(0, \text{min}(r_t, 10))\) can be changed to \(\text{max}(1, \text{min}((r_t b_t)^{-1}, r_t))\), where \(b_t = \sqrt{1 - \beta_2^t}/(1 - \beta_1^t)\) is the Adam bias correction term. This modification is called Paratrooper and forces RangerLARS to become more and more like Ranger as time goes on, reducing the noise in the weights. The convergence to the optimum is not slowed down, since RangerLARS dominates initially.

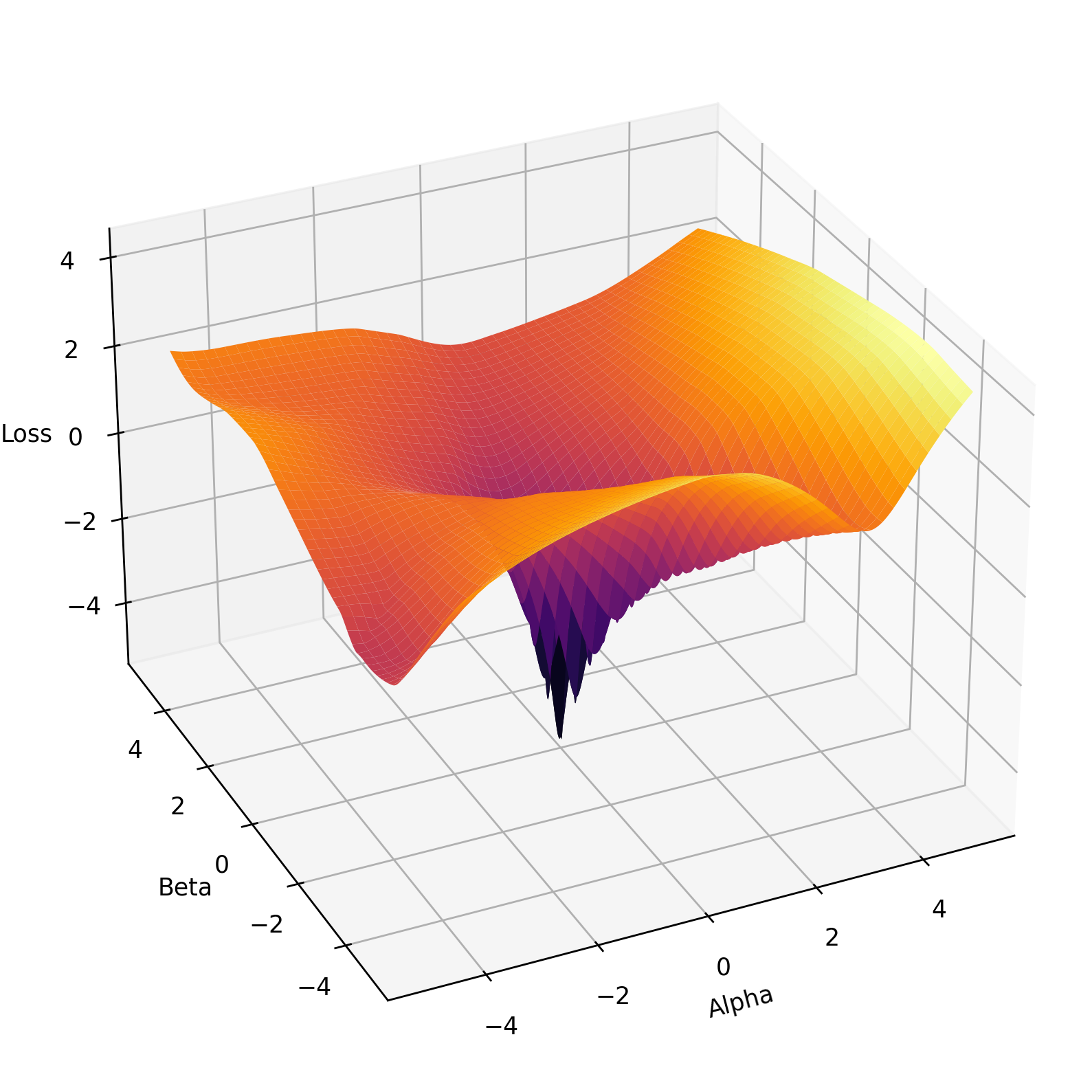

Loss landscapes. Deep learning optimizers have come a long way - they are becoming more complicated and more specialized. Like with most other things, complexity arises out of the desire to outperform current methods and designs. And rightfully so, because the optimization problems in deep learning are hard. Let's end by quickly exploring how to get a sense of what we're up against.

Obviously, the loss landscape is very high-dimensional and there's no way to visualize it in a 2D or 3D plot. However, we can get a very approximate, and maybe inaccurate plot using the following procedure [7]:

- Train a network to obtain a minimum \(\theta^*\)

- Sample two new random sets of weights \(\theta'\) and \(\theta''\)

- Plot the 3D surface of the points \((\alpha, \beta, \mathcal{L}(\theta^* + \alpha \theta' + \beta \theta''))\).

Figure 2 shows one loss landscape found using this method. The task is a simple noise-free regression of a sine. We train a small 3 layer net with ReLUs to obtain the optimal weights \(\theta^*\). Then we sample two random sets of weights \(\theta'\) and \(\theta''\), and linearly interpolate the optimal weights with the random ones based on a two dimensional grid of coefficients \(alpha\) and \(beta\). Then, we evaluate all of the resulting networks on the loss and plot that.

Implementation-wise, I think this use-case is where JAX shines. When linearly interpolating the weights based on the coefficients we can vmap the interpolation function for a single \((\alpha, \beta)\) combination to get wildly improved performance. Similarly, for the evaluation, the functional style of JAX allows us to vmap the function call itself across the parameters. This basically allows us to evaluate many different networks in an efficient manner as if they were simply elements in a vector.

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

import jax.tree_util

# The neural network model

def neural_network(params, inputs):

...

return outputs

def create_weights(alpha, beta, ref_point, pert1, pert2):

"""

alpha: float

beta: float

ref_point: the optimal weights

pert1: perturbed set of weights

pert2: perturbed set of weights

"""

return jax.tree_util.tree_map(

lambda pert1, pert2, ref_point: ref_point + alpha * pert1 + beta * pert2,

pert1, pert2, ref_point)

# The optimal weights and the random sets

reference_point = ...

perturbation1 = ...

perturbation2 = ...

# Weight combinations

alphas = jnp.linspace(-5, 5, 100)

betas = jnp.linspace(-5, 5, 100)

ALPHA, BETA = jnp.meshgrid(alphas, betas)

alphas = ALPHA.ravel()

betas = BETA.ravel()

# Evaluate losses

perturbed_params = vmap(create_weights,

in_axes=(0, 0, None, None, None))(alphas, betas,

reference_point, perturbation1, perturbation2)

preds = vmap(neural_network, in_axes=(0, None))(perturbed_params, inputs)

losses = np.log(((preds - targets)**2).mean(1))

References

[1] Duchi, J., Hazan, E., Singer, Y. Adaptive Subgradient Methods for Online Learning and Stochastic Optimization Journal of Machine Learning Research 12 (2011).

[2] Kingma, D. P., Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

[3] Liu, L. et al. On the Variance of the Adaptive Learning Rate and Beyond arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.03265 (2019).

[4] Zhang, M. R. et al. Lookahead Optimizer: k steps forward, 1 step back arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.08610 (2019).

[5] You, Y., Gitman, I., Ginsburg, B. Large Batch Training of Convolutional Networks arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.03888 (2017).

[6] You, Y. et al. Large Batch Optimization for Deep Learning: Training BERT in 76 minutes arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.00962 (2021).

[7] Li, H., et al. Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets Advances in neural information processing systems 31 (2018).