Functional Deep Learning

JAX, the functional automatic differentiation library from Google, has established itself as a highly useful deep learning tool. It stands in stark contrast with the OOP approach of Torch and offers an interesting perspective to how deep learning systems can be built in an entirely functional approach. In reality, the boundaries between Torch and Jax are blurry, as nowadays flax has features which look like the OOP style of Torch, while functorch mimics the features of Jax. Nonetheless, Jax was the first of its kind and still carries heavy momentum when it comes to new projects implemented with it. Let's explore it a bit.

Jax is all about composable function transformations. It emphasizes pure functions with no side effects. The computational state is represented as an immutable object. As a result, to call the forward pass of the network you have to pass not only the inputs \(x\), but also the current parameters \(\theta\), the pseudorandom generator, and anything else needed. This is a curious deviation from Torch - it's closer to mathematical notation and facilitates the composition of multiple functional transforms. Speaking of which, the three main selling points here are grad - the ability to differentiate potentially any array with respect to any other one, jit - the ability to just-in-time compile code, and vmap - the ability to vectorize a function application across multiple arguments.

Let's take a peek at what happens under the hood. Jax is written mostly in pure Python so we can go quite far with just a debugger. Suppose you have a very simple function like

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax import grad

def f(x):

return x[0] + x[0] * x[1]

x = jnp.ones(5)

gradf = grad(f)

grad_at_x = gradf(x)

The function grad is built on top of vjp, the vector-Jacobian product function, so without loss of generality, we'll explore how entire Jacobians are computed. How does Jax represent Jacobians as composable transformations?

Consider that for a function \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\), the Jacobian is \(\partial f(\textbf{x}) \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\), a matrix. But we can also find a mapping from a specific \(x\) to the tangent space at that \(x\). For example, if \(f\) is one-dimensional, this mapping is given by \(\partial f(x) = f(x) + \frac{df(x)}{dx} (v - x)\). That is, we give the function a point \(x\) and it returns the equation for the tangent line at point \(x\), which is a new function of, say, variable \(v\). In higher dimensions, for a fixed \(\textbf{x}\), the tangent space is still a linear map from \(\textbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n\) to \(\textbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^m\)

where the Jacobian \(\partial f(\textbf{x})\) is the slope and \(\textbf{y}\) is a point on the tangent space, evaluated at \(\textbf{x}\). The signature of this function is \(\partial f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) because it takes a point \(\textbf{x}\) and returns the equation of the tangent space. Now we uncurry this function so that it takes a pair \((\textbf{x}, \textbf{v})\) and returns \(\partial f(\textbf{x}) \textbf{v}\), i.e. the tangent at \(\textbf{x}\) multiplied by \(\textbf{v}\), which is essentially the directional derivative of the tangent space at \(\textbf{x}\) in the direction \(\textbf{v}\). Jax calls \(\textbf{x}\) the primals and \(\textbf{v}\) the tangents. The function jvp takes in a function \(f\), primals \(\textbf{x}\) and tangents \(\textbf{v}\) and conveniently evaluates \((f(\textbf{x}), \partial f(\textbf{x}) \textbf{v})\) using forward differentiation.

With jvp there is no backward pass. To compute the derivatives, for each primitive operation in the function Jax uses a JVP-rule which calculates the function value at the primals and the corresponding JVP. Deep within jvp it creates a WrappedFun, this being the type representing a function to compose with transformations, and adds the jvp transformation to its transform stack. Through a method call_wrapped it begins applying the transforms. We reach a generator called jvpfun which actually does the computation. It creates a special JVPTrace object which acts as a context manager. These tracers are key: they are abstract stand-ins for array objects, and are passed to JAX functions in order to extract the sequence of operations that the function encodes. Further down, the entire calculation is traced (parsed) into a JVPTracer object which contains actual primal and tangent values, and an actual sequence of primitive computations. Each of these contains its parameters, such as the start index, strides, and so on for a slice primitive, or the dimension for a squeeze primitive, or a full jaxpr to execute for a pjit primitive. These are evaluated one by one according to their rules.

Thus jvp calculates the derivatives in a bottom-up manner by propagating the primal values and the tangents along the traced function. The tangent gets multiplied according to the rules of calculus. If we set the the initial tangent value to a one-hot vector, we'll get the corresponding column in the Jacobian as output. Setting the tangent to a unit vector will produce a directional derivative in the unit direction - not the Jacobian! To get the full Jacobian, we have to run the forward pass \(n\) times. For that reason forward mode AD is preferred when the function outputs many more elements than it takes as input. Here's an important chunk from jacfwd.

pushfwd: Callable = partial(_jvp, f_partial, dyn_args)

y, jac = vmap(pushfwd, out_axes=(None, -1))(_std_basis(dyn_args))

The function jacrev calculates the Jacobian using reverse mode AD in a fairly similar manner. Except that now the it uses vjp which models the mapping \((\textbf{x}, \textbf{v}) \mapsto (f(x), \partial f(\textbf{x})^T \textbf{v})\). It lets us build Jacobian matrices one row at a time which is more efficient in cases like deep learning, where Jacobians are wider. Also the function grad computes the whole gradient in a single call. The downside is that the space complexity of this is linear in the depth of the computation graph.

Here's a high level of how vjp works. It takes any traceable function and the primals and linearizes it, obtaining a tangent function at the primals. The linearization actually uses jvp inside of it and produces a jaxpr, traced from the forward pass. Subsequently we return a complicated-beyond-comprehension wrapped function which contains the jaxpr, the constants, and all other context. This function actually has a call to backward_pass inside it and is designed to accept the equivalents of \(\textbf{v}\). These are all wrappers capturing the necessary context from the forward pass. At the end, we actually evaluate this function by passing a few one-hot encoded vectors, obtaining our Jacobian.

In addition to tracing the function Jax works by converting it to an intermediate representation called a Jaxpr - a Jax expression. As we've already seen these jaxprs pop up at various places to allow for the detailed interpretation of the computations. The jaxpr for our function above is

{ lambda ; a:f32[5]. let

b:f32[1] = slice[limit_indices=(1,) start_indices=(0,) strides=None] a

c:f32[] = squeeze[dimensions=(0,)] b

d:f32[1] = slice[limit_indices=(1,) start_indices=(0,) strides=None] a

e:f32[] = squeeze[dimensions=(0,)] d

f:f32[1] = slice[limit_indices=(2,) start_indices=(1,) strides=None] a

g:f32[] = squeeze[dimensions=(0,)] f

h:f32[] = mul e g

i:f32[] = add c h

in (i,) }

Here we've passed an input array of shape \((5,)\) even though only two elements are used, which is not a problem. These jaxprs are very rich in functionality - each operation can be inspected and modified. Each line of the jaxpr is an equation with input and output variables, the primitive, its parameters, and so on, that can be evaluated.

Other functional transforms work in a similar way - they trace the computation into a jaxpr, modify it optimize it, and run it. Consider jit. It relies on Google's powerful XLA compiler. XLA does not typically create .so files in the way traditional compilers might output executable or linkable binaries. Instead, XLA generates machine code dynamically at runtime, which is directly executed in-memory. This approach is aligned with how JIT compilation typically works - compiling code when it is needed, without creating persistent binary files on disk.

The vectorizing transform, vmap pushes a new axis to the jaxpr along which the function will be vectorized. If it's not vectorized, the function has to be called separately on many inputs, producing multiple XLA calls. vmap speeds this up noticeably by simply adding the new index in the jaxpr, which shows up usually as fewer calls. After all, when you've traced the computation graph you know the exact shapes and dtypes, so adding the new axis in the right places is not impossible. The parallelization transform pmap vectorizes and splits the batch across the available devices, producing actual parallelism.

So where does Jax shine? Here are a few cool examples. First is jax.lax.scan, which essentially unrolls a function across time, while carrying over the state. Recurrent modules like LSTM and GRU are exactly of this type - you provide the initial hidden/cell state and unroll the computation graph for a few steps. Similarly, in RL the scan function can provide perform entire episode roll-outs - you give bundle the environment step function and the action selection function together and give it to scan, along with the initial state. Super useful.

Another example where Jax fits well is with optimizers. The Optax library is pretty good for this. It offers perhaps one of the most intuitive interfaces for setting up optimizers, chaining optimizers, lr schedules, postprocessing gradients, all because of the functional nature of Jax. Let's take a look at some curious optimizers from it.

First consider that given any meaningful minimization problem gradient descent is guaranteed to reach a local minima, if such exists. However, in min-max problems standard gradient descent may not converge. And these settings are not that exotic, they show up in generative adversarial networks, constrained RL, federated learning, adversarial attacks, network verification, game-theoretic simulations and so on. For the simplest case suppose you're optimizing \( \min_{x \in \mathbb{R}} \max_{y \in \mathbb{R}} f(x, y).\) The update rules with gradient descent would be the following, which in fact may oscillate or diverge:

Optimistic gradient descent does manage to converge, but it uses a memory-based negative momentum, which requires keeping the past state of the entire set of parameters:

As a second example, consider Model Agnostic Meta Learning (MAML), a classic. MAML optimizes \(\mathcal{L}(\theta - \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta, \textbf{X}, \textbf{Y}), \textbf{X}', \textbf{Y}')\). That is, we have a set of samples and targets \((\textbf{X}, \textbf{Y})\), perhaps for one particular task, the current parameters \(\theta\), and we compute a few model updates on this data, obtaining new parameters \(\theta'\). This is the inner optimization step. Then, using \(\theta'\) and a new set of samples \((\textbf{X'}, \textbf{Y'})\), perhaps for a new task we calculate the loss and we calculate new gradients, which we subsequently apply. This is the outer step. We can think of it as a differentiable cross-validation with respect to the model parameters. Implementing this in PyTorch is tricky (speaking from experience) because only the parameter updates from the outer loop are actually applied. The params from the inner loop are used only temporarily. In Jax the whole MAML setup is less than 30 lines of code.

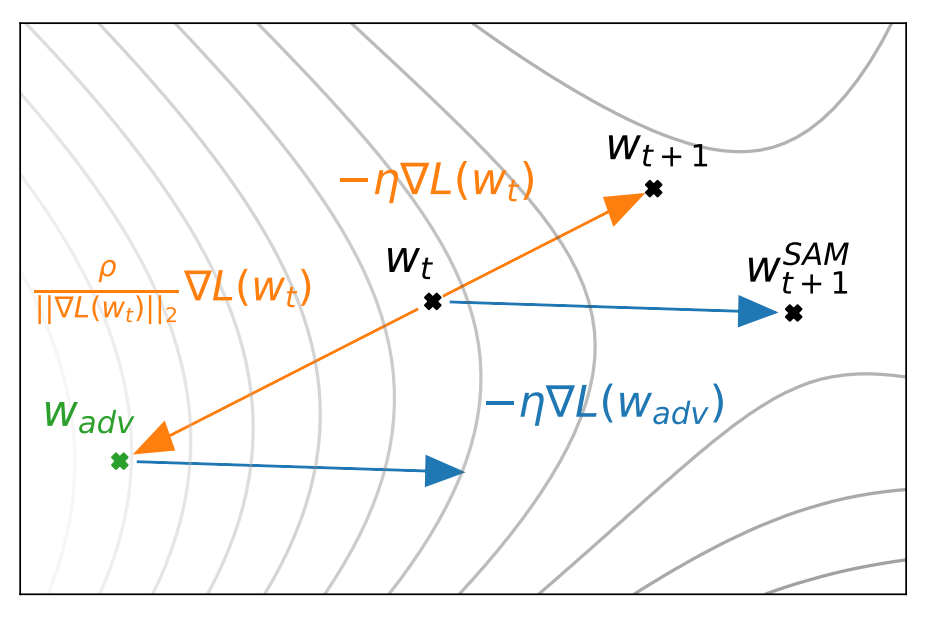

As a third example, consider sharpness-aware-minimization (SAM). The idea here is to find points in the parameter spece which not only have a low loss but are in a neighborhood where all nearby points have uniformly low loss. Let \(\mathcal{S}\) be the training set, \(\textbf{w}\) the model weights, and \(L_\mathcal{S}\) be the loss function. Then, SAM optimizes

which is interpreted as follows. When at \(\textbf{w}\), we first find the adversarial vector \(\boldsymbol{\epsilon}\) which maximally increases the loss. For this to be meaningful \(\boldsymbol{\epsilon}\) has to be bounded. Then we minimize the loss at the perturbed set of weights. This ensures that we minimize the loss at the sharpest point in the neighborhood. In practice, one uses an approximation to the \(\nabla_w L_\mathcal{S}^{\text{SAM}}\). The optimal value of \(\boldsymbol{\epsilon}\) from the inner maximization problem depends on the gradients at \(\textbf{w}\), so in reality one computes two sets of gradients - one at \(\textbf{w}\) and one at \(\textbf{w} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}\). In most most cases this additional computation is worth it, as SAM typically yields noticeable improvements over SGD or Adam.