Generative Models: Diffusion

Diffusion models have take the world by storm. They have proved able to learn complicated distributions with impressive accuracy, enough to have real-world general-purpose utility. Their widespread use in text-to-image models is now evident and, interestingly, is spreading to many other problem settings. I have purposefully waited quite some time for the hype to settle down. But now, when expectations are more realistic, it's time to explore these curious models and the real impact they have on the current state of deep learning.

To begin, one should realize that denoising is intrinsically tied to generation. Adding noise to the data in most cases permanently destroys parts of the sample. If the scale of the noise is too big, at some point it overwhelms the useful signal rendering the resulting noisy sample indistinguishable from randomness. But in the reverse process of denoising the sample, you still have to produce those features which have been corrupted. Basic denoising methods such as mean or median filtering do not learn and hence the quality of their results is bounded by the noise levels. But other methods do learn. And if the noise levels are overwhelming, to the point where you don't see most of the clean features, the process of denoising becomes more and more like generation. This is the high-level intuition behind diffusion - we define a process which adds noise to the data, called the forward process, and train a parametric model to denoise it, this being the reverse process. At test time, we feed random noise to the model, which being trained to denoise anything, will transform this noise to a sample from the original data distribution.

Suppose we have a training dataset of samples and the underlying data distribution is \(\mathcal{D}\). The whole diffusion pipeline can be applied independently across all samples. For that reason, let's consider a single sample \(\textbf{x} \sim \mathcal{D}\). We can define a stochastic process which, at each step, adds noise to it. For simplicity, assume we add Gaussian noise independently to each dimension of the sample. If \(\textbf{x}\) is an image, we'd add independent noise to the intensity of each pixel. If \(\textbf{x}\) is a point in some geometric space, then we add noise to its coordinates. If \(\textbf{x}\) represents a sample with physically-meaningful dimensions, we simply add noise to their measurements.

Doing this for multiple steps, we get a discrete random walk. One common and highly practical example definition for the stochastic process governing it is:

Here \(\textbf{x}_0\) is the clean sample. The index \(t\) indicates the time step for the random walk, which is typically limited to some upper range \(T\). The process is parameterized by a sequence \(\beta_1, ..., \beta_T\) - usually some monotone function in \([0, 1]\). The previous noisy sample \(\textbf{x}_{t}\) is scaled by \(\sqrt{1 - \beta_{t+1}}\) which pushes it towards \(0\). If \(\textbf{x}\) is properly normalized, the added noise is independent of its range of values, which is convenient.

This exact process is useful because it allows for a close-form calculation for the resulting distribution of \(\textbf{x}_t\) after \(t\) total steps. Thus, to compute \(\textbf{x}_{t+2}\) from \(\textbf{x}_t\) one does not need to simulate the process for two steps but can use appropriate formulas to get the distribution at \(t+2\) directly:

In general, for any \(t\) the distribution is given by

where we have set \( \alpha_t = 1 - \beta_t\) and \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{i=1}^t \alpha_i\) for convenience. Another useful property is that under some mild conditions on the variance schedule \(\beta_i\), the distribution of \(\textbf{x}_t\) converges to an isotropic Gaussian as \(T \rightarrow \infty\). More generally \(\textbf{x}_{1:T} | \textbf{x}_0\) is a Guassian process and hence \(\textbf{x}_{t-1} | \textbf{x}_t, \textbf{x}_0\) is also Gaussian. Consider the implications of this: if we know the clean sample \(\mathbf{x}_0\), then we can obtain analytic distributions for the denoised sample, \(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\). However, at test time we don't have \(\textbf{x}_0\) and the distribution of \(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t\) is a complicated mixture. Our strategy will be to obtain an estimate of \(\mathbf{x}_0\) and then sample from the Gaussian distribution of \(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\). However, if we already have an estimate of \(\mathbf{x}_0\) why bother to denoise?

Note that if we train a predictor to output directly \(\mathbf{x}_0\) from \((\mathbf{x}_t, t)\), at test time when we give it \((\mathbf{x}_T, T)\) it will output something very blurry because \(\mathbf{x}_T\) is uncorrelated with any sample from the target distribution. Hence, the best predictor given fully random noise is the average of the data distribution. The iterative denoising is needed because it allows the model to take this blurry image and progressively denoise it, randomly bringing it into one particular part of the data manifold, where specific clearcut features start to emerge.

The observed target distribution is \(p(\textbf{x}_0)\) and \(p(\textbf{x}_{1:T} | \textbf{x}_0)\) is the latent distribution. We denote the learned distribution as \(p_\theta(\mathbf{x}_0)\) and the corresponding latent distribution as \(p_\theta(\textbf{x}_{1:T} | \textbf{x}_0)\). We'll maximize a lower bound on the likelihood of the target samples under our distribution:

Thus, instead of maximizing the likelihood of the observed data, we maximize a lower bound, the ELBO. Now from the last expression we can pick out only those terms that depend on \(\theta\). Given that \(p_\theta(\textbf{x}_T) = \mathcal{N}(\textbf{0}, \textbf{I})\), we formulate the following loss function:

Now, we need \(p_\theta(\textbf{x}_{t-1} | \textbf{x}_t)\) to be something easy to evaluate, like a Gaussian. But \(\textbf{x}_{t-1} | \textbf{x}_t\) does not have a Gaussian distribution, \(\textbf{x}_{t-1} | \textbf{x}_t, \textbf{x}_0\) does. So we need to have a neural network that estimates \(\textbf{x}_0\). In practice, we can easily get \(\textbf{x}_0\) since it is related to \(\textbf{x}_t\) through the noise \(\epsilon_t\),

Therefore we can have the network predict the noise, obtaining \(\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t)\). Once we have an estimate of the noise, we essentially have an estimate of \(\textbf{x}_0\) and in turn can evaluate \(\textbf{x}_{t-1} | \textbf{x}_t, \textbf{x}_0\). The variance is usually fixed to some constant as predicting it introduces instability. The formula for the estimated mean is

This is roughly how denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPM) work [1]. At training time the network learns to estimate the noise. At test time, we start with a single sample \(\textbf{x}_T\) from the prior, a Gaussian, call the model to obtain \(\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_T)\), compute \(\mu_\theta(\textbf{x}_{T-1} | \textbf{x}_T)\) analytically and sample \(\textbf{x}_{T-1}\) from the estimated distribution of \(\textbf{x}_{T-1} | \textbf{x}_T\). Repeat autoregressively until we get to \(\textbf{x}_0\). Note that because of the intermediate sampling, even it we start from the same noisy \(\textbf{x}_T\) multiple times, we will always get different generated samples.

Score-Based Generative Modeling

There is another diffusion formulation which is quite intuitive - that of score matching. Given a distribution \(p(\textbf{x})\), the score \(s(\textbf{x})\) is simply the gradient of the log-likelihood, \(\nabla_\textbf{x} \ln p(\textbf{x})\). It's an attractive quantity because it doesn't require calculating any intractable normalization constants. But how is it related to sample generation?

One usage of the score is in stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics (SGLD), a curious, perhaps even beautiful, method for sampling from physics/thermodynamics. Suppose we start from a sample \(\textbf{x}_0\). To, get a sample from the target distribution \(p(\textbf{x})\) we can simply do log-likelihood ascent, with added noise injection:

Overall this very closely resembles gradient ascent. As long as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) and \(\epsilon \rightarrow \textbf{0}\), \(\textbf{x}_t\) will be a sample from \(p(\textbf{x})\). The added noise at each step is necessary, otherwise the sequence will converge to a local minimum and will depend on the starting location. So if we train a model for the score, \(s_\theta(\cdot)\), we can just plug it in the Langevin equation and iterate to get a sample. This is the inference approach of score-based sample generation.

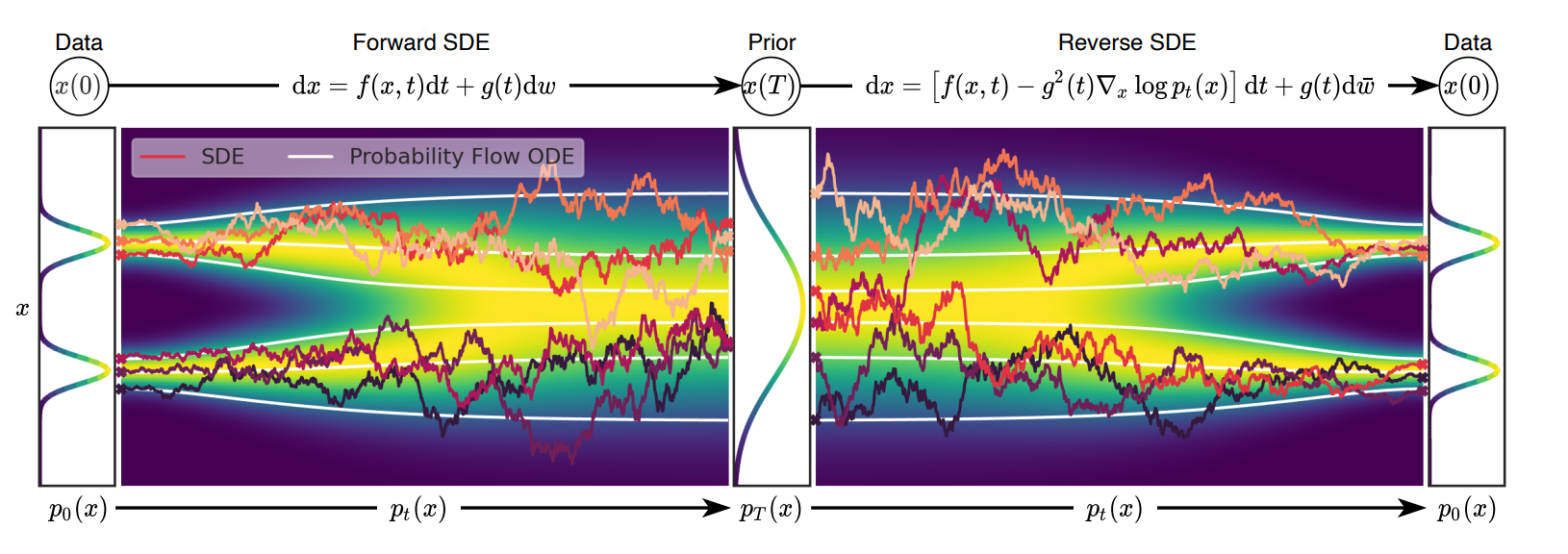

The training process here is called score matching because the network attempts to accurately match the true score. Similarly to DDPMs, one needs to define a finite sequence of noise scales which are used to perturb the input samples. However, it's useful to see also the case where the diffusion time is continuous [2]. Suppose \(t\) is continuous and in \([0, T]\). The forward process adding noise to the data can now be modeled as the SDE

where \(f(\textbf{x}, t)\) is the drift term, \(g(t)\) is a diffusion term, and \(\textbf{w}\) is a Wiener process. For simplicity, the diffusion term is a scalar, not depending on \(\textbf{x}\). This is a general formulation. Given this, it is a known mathematical fact that there exists a reverse diffusion process, modeled by a reverse SDE:

Here \(dt\) is a infinitesimal negative timestep and \(\bar{\textbf{w}}\) is a Wiener process where time flows backward from \(T\) to \(0\). As we can see, if we have the score, we can reverse the process. Thus, to learn the score, we construct a network \(s_\theta\) that takes in \((\textbf{x}(t), t)\) and is trained to solve the following simplified objective

Note that here, depending on the exact SDE, \(p(\textbf{x}(t) | \textbf{x}(0))\) may or may not be computable efficiently. If the drift coefficients are affine, then this probability is Gaussian and can be computed easily. For more advanced ones, one can use Kolmogorov's forward equation or simply simulate it.

Consider the benefit of adding noise for training the score network. Without adding noise the ground-truth score can be evaluated only at the samples in the dataset. But the first sample \(\textbf{x}(T)\) from the prior at test time may be very far from the data distribution. Hence, if you don't have data points around the space where your prior has high density your score estimate won't be accurate at those locations. To alleviate this, the forward diffusion effectively performs annealing. Adding the noise allows us to learn the score over a larger and more smooth region, covering the path from the data distribution to the prior one.

The DDPM model that we discussed above can written in both its discrete and continuous versions:

Other discrete diffusion formulations also have similarly-looking continuous SDEs. But once we have trained the score network, how do we actually generate a sample using the reverse SDE? Well, we use a numerical SDE solver like the Euler-Maruyama or the stochastic Runge-Kutta. These solvers discretize the SDE in tiny steps and iterate in a manner similar to Langevin dynamics, adding a small amount of noise at every step.

Importantly, it can be proved that the DDPMs and the score-based methods are equivalent [3]. It takes some math to see this, but at the end one can reparametrize the DDPM to produce scores. In fact, the relation is relatively simple: \(\nabla_{\textbf{x}_t} \log p(\textbf{x}_t) = - \epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t) / \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}\). The formulas and the loss function are adjusted accordingly. This produces a unified perspective - the network can use the noisy \((\textbf{x}_t, t)\) to predict either \(\textbf{x}_0\), or \(\epsilon_t\), or \(\nabla_\textbf{x} \log p(\textbf{x}_t)\) - all will work, but will require different denoising formulas for the test time refinements.

Practical Considerations

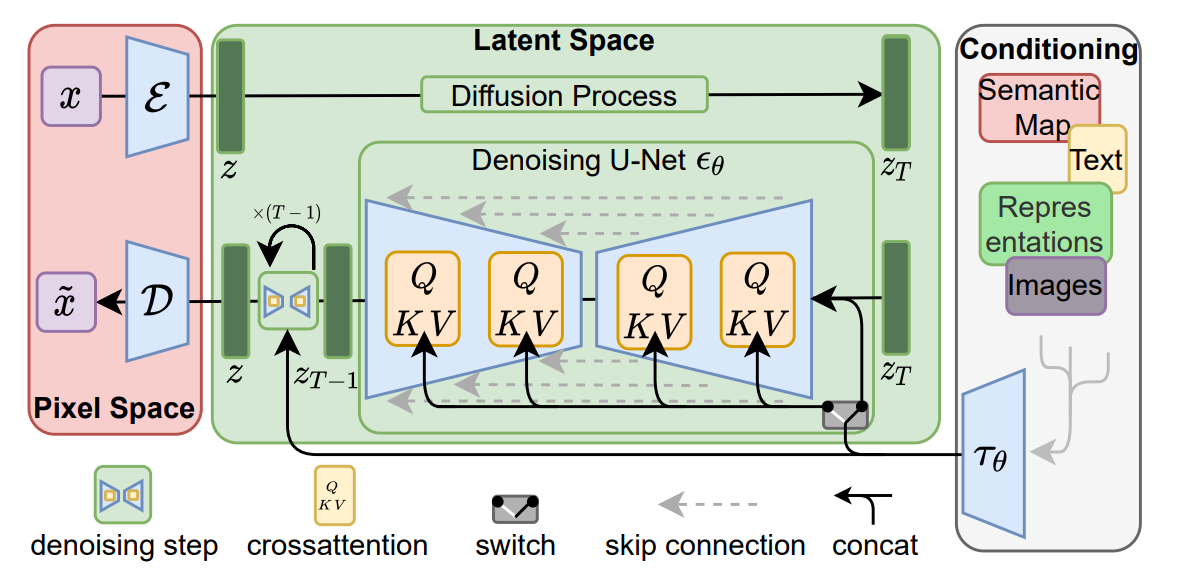

Naturally, to be able to learn \(\epsilon_t\), \(\textbf{x}_0\), or \(\nabla_\textbf{x} \log p(\textbf{x}_t)\), especially when \(\textbf{x}\) is very high-dimensional, one needs to have a big model. Denoising architectures with skip connections, like U-Nets, or pure transformer-based approaches, for example for non-image data, are the go-to choice.

Apart from model size, one needs to consider also the inference speed. With DDPMs you have to iterate from \(T\) to \(1\), which in practice is simply too slow. One straightforward approach is to simply denoise once every \(S\) steps, for a total of \(\lfloor T/S \rfloor\) denoising calls. Since the model has learned to produce a meaningful output for all \((\textbf{x}_t, t)\), we are simply calling it \(S\) times less, even though we are slightly biasing it. Another similar approach is given by denoising diffusion implicit models (DDIM) [4], which requires some effort to fully understand, but it's worth it.

To speed up the generation, one needs to come up with an inference process that simply uses less steps. The objective optimized by DDPM only depends on \(p(\textbf{x}_t | \textbf{x}_0)\), not on \(p(\textbf{x}_{1:T})\). In principle, there are many processes that have the same \(p(\textbf{x}_t | \textbf{x}_0)\), but may not be Markovian. This, in turn can be used to speed up the generation of new samples. One can consider the following:

Here \(p_\sigma(\textbf{x}_t | \textbf{x}_0) = \mathcal{N}(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \textbf{x}_0, (1 - \bar{\alpha}_t) \textbf{I})\) which still matches DDPM in that it is easy to evaluate, however the "forward" process \(p_\sigma(\textbf{x}_t | \textbf{x}_{t-1}, \textbf{x}_0)\) is no longer Markovian. The quantity \(\sigma\) is an important parameter that controls the stochasticity of the forward process. For one exact \(\sigma\), we get DDPM, which is Markovian. If \(\sigma_t = 0, \forall t\) the process becomes deterministic. Thus, DDIMs are a generalization of DDPMs because they support non-Markovian and even deterministic processes.

The generative model \(p_\theta\) is constructed similarly to \(p_\sigma\). Sampling \(\textbf{x}_{t-1}\) from \(\textbf{x}_t\) is calculated as:

Notice how here to generate \(\textbf{x}_{t-1}\) you need to know both \(\bar{\alpha}_t\) and \(\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}\). This means that you can have irregularly spaced \(\alpha_t\) coefficients. All that matters is the current and the next one. Thus, DDIM allows one to define a forward process on only a small subset of timesteps from \(\{1, 2, ..., T\}\), which in turns greatly speeds up the reverse generative process. It does not require retraining, just changing the calculations during the generation phase.

Apart from DDIM, one can typically get a huge inference speed improvement by doing diffusion in a latent space, as opposed to for example the high dimensional sample space of images [5]. To train a latent diffusion model one uses an encoder, like a VQ-VAE or something similar, to map the clean input to a latent space. In the latent space we add noise and pass the noisy variable to a U-Net which denoises it. Subsequently, this variable is fed to a decoder which upsamples and decodes back into the modality of interest. It is common also to have additional modality-specific encoders for any data that will condition the diffusion process. A cross-attention block in the U-Net handles the conditioning.

This idea of latent diffusion is incredibly powerful. It allows diffusion to be used in, realistically, all kinds of contexts. Using separate encoders and decoders allows one to build multi-modal generative models that can condition one signal on any other and can produce any signal modality from any other. Consider a model like Marigold [6]. They take a latent diffusion model and finetune it on synthetic (image, depth) pairs. The encoder transforms both RGB and depth (itself treated as a grayscaled image) into the latent space. The decoder maps the latent into a depth image. The result is a strong diffusion model for depth prediction.

And as these systems become more multi-modal, the importance of accurate conditioning only grows. Suppose we want to generate an image conditional on a high-level semantic label \(y\) and we are given a classifier \(f_\phi(\textbf{x}_t, t)\) that uses the current noisy images. Then, the score of the joint distribution \(p(\textbf{x}_t, y)\) is:

The second line results from a first-order Taylor approximation of \(\log p(y | \textbf{x}_t)\). Thus, to make our diffusion model condition on the semantics \(y\), one needs to adjust the model output by a scaled gradient of the classifier - simply use \(\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t) - \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \nabla_{\textbf{x}_t} \log f_\phi(y | \textbf{x}_t)\) instead of \(\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t)\). The interpretation is that now one learns the score of the joint distribution. This method is called classifier guided diffusion [7].

A slightly more popular approach is classifier-free guidance, where one does not have a separate classifier but instead uses the same model - sometimes conditioning on the signal \(y\), sometimes not [8]. This produces an implicit classifier. Its gradient is given by

One can then easily derive that the quantity to be used instead of \(\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t)\) in the subsequent calculations becomes actually \((1 + w)\epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t, y) - w \epsilon_\theta(\textbf{x}_t, t, y = \emptyset)\). We have added a weight \(w\) which shows how much the model should focus on the semantics \(y\) when generating the sample. The default value of \(1\) works reasonable.

With text-to-image models conditioning on the prompt requires us to be more careful. One of the principal difficulties here is that only nouns can be decoded to explicit visual objects, compared to modifiers like adjectives, adverbs, and propositions which modify the appearance of objects or the positional relationships between them. Additionally, learning content and style separately has been somewhat possible, as there are methods which can do it, but it's far from a solved matter. A famous technique here is textual inversion [10] - one finetunes a latent diffusion model on a small set of target images of a specific object, along with captions like "A photo of a \(S_*\)", where \(S_*\) is the object. The model only learns the embedding for the token \(S_*\) after which it can refer to it.

Regarding the cultural effects of AI-generated images, I believe the evidence speaks for itself. Depending on the prompt, these models can produce images that can realistically be considered artwork, sometimes being indistinguishable from actual paintings by human artists. Yes, one can flood the art market with tons of new generated images, rendering human art close to worthless, but so what? The end consumer will only benefit from this. Text-to-image AI models will likely reduce the elitist status of visual art and will force people to appreciate an image, or a painting, for its actual content, not for the career, name, or personality of its creator. We should value paintings only based on how much their visual pattens resonate with our own experiences. In that context, AI art is art, by whatever non-humancentric definiton we adopt. We should be optimistic, because the best artworks are yet to come... and they won'be envisaged by a human brain.

References

[1] Ho, Jonathan, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 6840-6851.

[2] Song, Yang, et al. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.13456 (2020).

[3] Luo, Calvin. Understanding diffusion models: A unified perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.11970 (2022).

[4] Song, Jiaming, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02502 (2020).

[5] Rombach, Robin, et al. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022.

[6] Ke, Bingxin, et al. Repurposing Diffusion-Based Image Generators for Monocular Depth Estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.02145 (2023).

[7] Dhariwal, Prafulla, and Alexander Nichol. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Advances in neural information processing systems 34 (2021): 8780-8794.

[8] Ho, Jonathan, and Tim Salimans. Classifier-free diffusion guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12598 (2022).

[9] Gal, Rinon, et al. An image is worth one word: Personalizing text-to-image generation using textual inversion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.01618 (2022).