Differentiable Rendering and Simulation

Being able to differentiate through the graphics rendering pipeline is a promising nascent technology that opens up the possibilities for tackling interesting vision problems of all kinds, from scene parameter estimation, to 3D modeling. Typically, in such cases one only has access to 2D images, and the task of finding the corresponding 3D representation is handled using analysis by synthesis - an approach where we render multiple candidate 2D images, compute a loss term, and propagate it back to the 3D scene attributes which we want to estimate. Such an approach requires differentiable rendering.

Rendering is the process of going from a 3D model of a scene to a 2D image. The 3D model typically consists of objects positioned at various locations, their material properties determining any reflections and shading types, and light sources. The rendering process can be roughly broken down into mathematical form as the composition of various operations like projecting from 3D to 2D, estimation of textures, normal vectors, shading, antialiasing, and sampling:

Here a 3D point has been projected to pixel coordinates \(P(x, y)\). Then we retrieve all spatially-varying factors (texture maps, normals) that live on the surfaces. The shading function \(\text{shade}\) models light-surface interactions. The 2D antialing is applied in continuous \((x, y)\) on the shaded result. The colour of pixel \(i\), \(I_i\) is finally obtained by sampling the result at the pixel center \((x_i, y_i)\).

The notation for the scene parameters is as follows: \(\theta_G\) is the geometry, \(\theta_C\) is the camera projection, \(\theta_M\) are the surface factors, \(\theta_L\) are the light sources. Suppose \(L(I)\) is a scalar photometric loss function on the rendered intensity \(I\). Then, differentiable rendering is about obtaining \(\partial L(I) / \{\theta_G, \theta_M, \theta_C, \theta_L \}\).

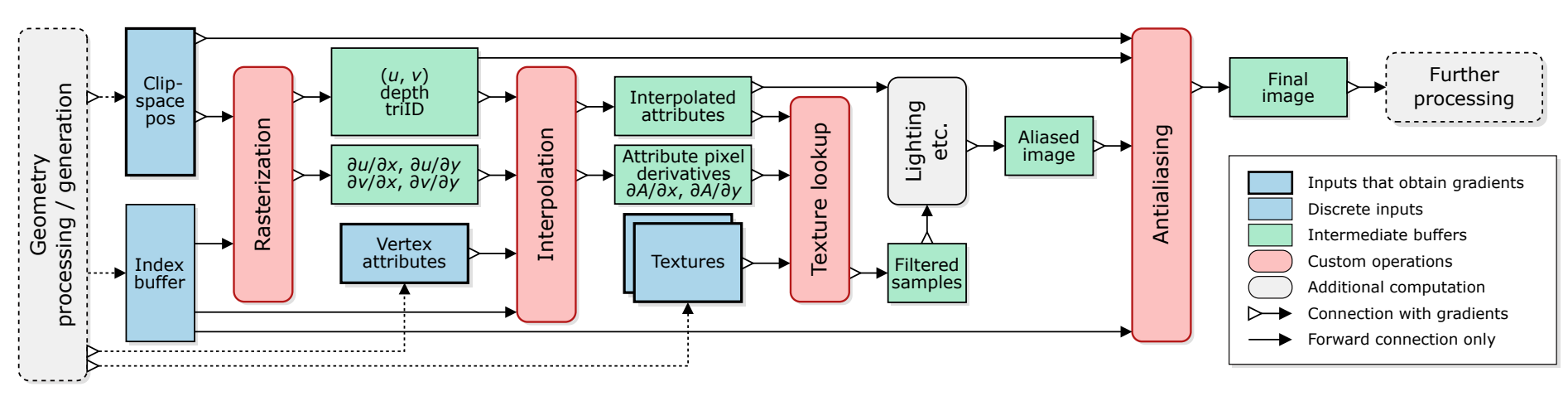

Building an engine for differentiable rasterization is not an easy task. Luckily, NVidia's diffrast is a very good attempt. It is modular and efficient, allowing for custom rendering pipelines parallelized on multiple GPUs. It has 4 rendering primitives, all of which support differentiation:

- Rasterization takes in triangles parameterized by their vertices in clip-space homogeneous coordinates, \((x_i, y_i, z_i, w_i)\), and returns for each image pixel the triangle covering it, the \((u, v)\) barycentric coordinates for the location of the pixel center within the triangle, and a depth measure, in normalized device coordinates (NDC).

- Interpolation means interpolating attributes like normals or textures which are available only on the vertices, at those positions specified by the barycentric coordinates \((u, v)\). Additionally, it is important to compute screen-space derivatives, showing how the attribute \(A\) changes as the screen pixels change, \(\partial A / \partial \{x, y\}\). This is needed for the next step.

- Texture filtering maps 2D textures to the object. This happens using mipmapping. The core idea is to precompute and store several downscaled, lower-resolution versions (mipmaps) of a texture and then use the most appropriate one, or a combination of them, during rendering based on how the texture is projected onto the screen. The base texture is called Level of Detail 0 (LOD0). If the object is far away and the texture covers fewer screen pixels, as calculated from the screen-space derivatives from the previous step, a lower-resolution mipmap (such as 128×128) is selected, to reduce aliasing. Since the LOD can be fractional, trilinear interpolation is used across the eight texels from the nearest two mipmap levels.

- Antialiasing aims to reduce the sharp intensity discontinuities that arise from many common graphics operations. Here's how it works. Since for each pixel we have the triangle ID that is rasterized into it, we can detect silhouette edges based on ID discontinuities. Suppose points \(p\) and \(q\) are the endpoints of this edge. The edge \(pq\) intersects the line connecting neighboring horizontal or vertical pixel centers. Based on \(p\) and \(q\), we can linearly blend the colors of one pixel into the other one. This antialiasing method is differentiable because the resulting pixel colors are continuous functions of positions of \(p\) and \(q\).

The antialiasing improves image quality only marginally, so why do we bother with it? Turns out it has a very important role - to allow us to obtain gradients w.r.t. occlusion, visibility, and coverage. Everything before the antialiasing is point-sampled, meaning that calculations happen only at the pixel centers. Therefore, the coverage, i.e., which triangle is rasterized to which pixel, changes discontinuously in the rasterization operation. Hence, it cannot be easily differentiated w.r.t. vertex coordinates. The antialiasing computations approximate the area of a triangle over a pixel and therefore allow this quantity to depend continuously on the positions of the vertices.

The four rendering primitives make Nvdiffrast quite a powerful library. It allows us to solve problems where:

- We have to find where in 3D space certain vertices are positioned so that a photometric loss to a ground truth image is minimized. The rasterization is the important phase here.

- We have to estimate per-vertex material parameters or reflections. These can be framed as per-vertex attributes and affect the interpolation.

- We have to learn any kind of abstract field that is used in downstream processing. This field can be modeled as a multi-channel texture used in the texture-mapping phase.

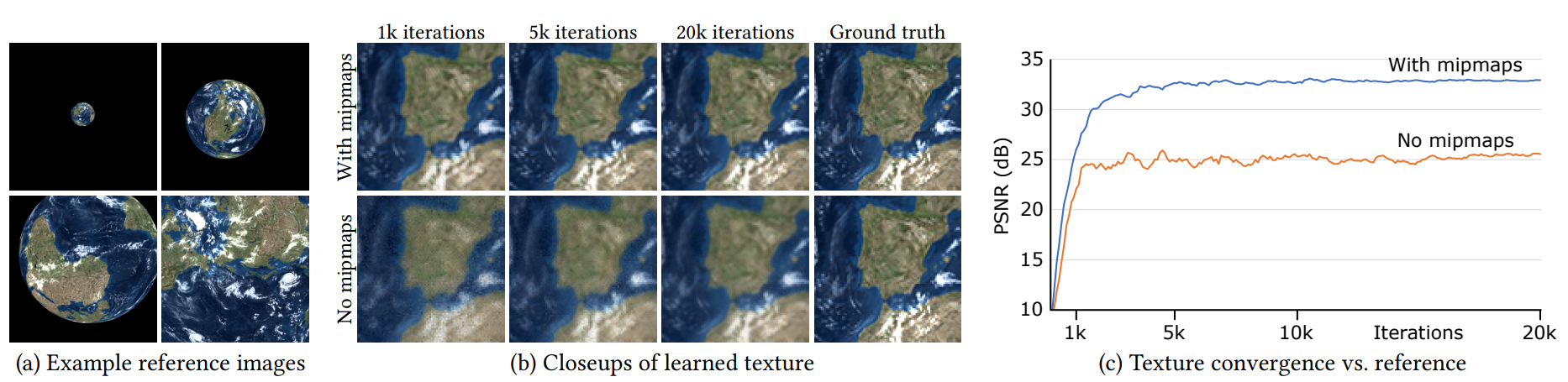

Let's see some examples. Fig. 2 shows an example where we have to learn a texture which when mapped to a unit sphere and rendered, produces various reference images. Without mipmaps we get a lot of aliasing, which prevents gradients from converging to the right minimum.

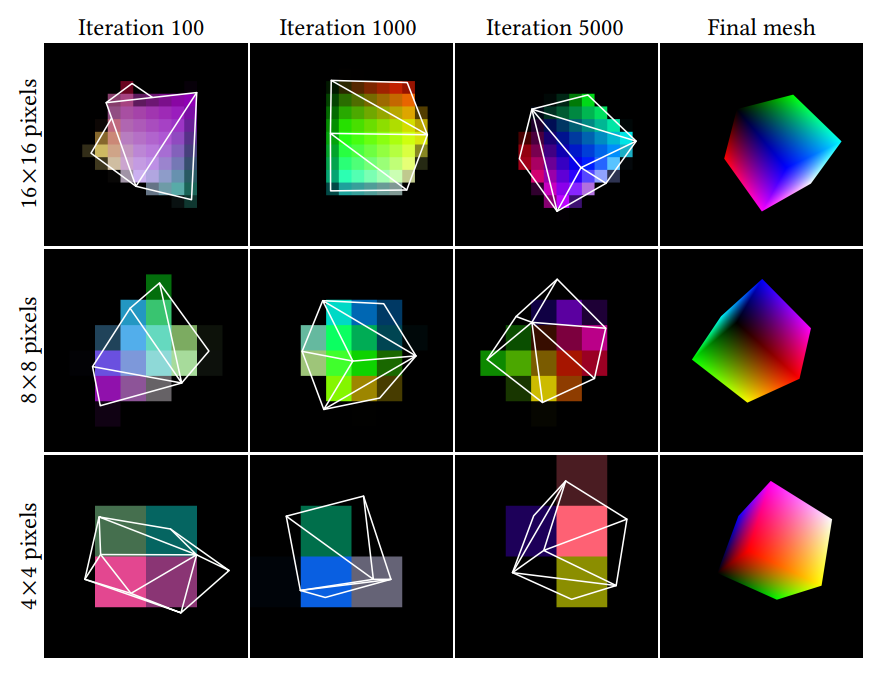

Fig. 3 shows a simple experiment where the goal is to learn the vertex positions and colors of a small mesh, such that when rendered we get a bunch of reference images. The interesting thing however is that the photometric loss is calculated in very small resolutions like 4x4, 8x8, or 16x16. As the resolution drops, the average triangle starts to cover very few pixels, yet the antialiasing gradients still provide useful information.

Other, more complicated things are also possible. For example, one can estimate environment maps and Phong BRDF parameters from a given irregular mesh. This means we're estimating textures such that when mapped to highly reflective irregularly-shaped object, the rendered results looks in a certain way, given by the reference images.

Nvdiffrast is not the only differentiable rendering library out there. Pytorch3D and TensorFlow Graphics are similar rasterization-based ones. Compared to them, a particularly interesting one is Mitsuba which uses ray-tracing and can account for inter-reflection, shadowing, and other physical effects. It is based on Dr.Jit - a library for just-in-time compilation, specialized for differentiable rendering. In Mitsuba, the input consists of the scene objects: camera, light sources, shapes, textures, volumes, scattering functions for surfaces and volumes, the actual rendering algorithm (so called integrator), the sampling strategy, and potentially other elements like color spectra. The output consists of the rendered image and possibly its computed derivatives.

Ray-tracing is the other big way to do rendering. Compared to rasterization, which finds which pixels are influenced by each scene object, ray-tracing works by finding which scene objects are influenced by each pixel. It relies on the rendering equation, which models the radiance in a particular location and viewing direction:

Here \(L_0(x, \omega_0)\) is the outgoing radiance at point \(x\) in direction \(\omega_0\), \(L_e(x, \omega_0)\) is the emitted radiance in that point and direction, \(\Omega\) is a hemisphere of incoming directions, \(L_i(x, \omega_i)\) is the incoming radiance, typically computed recursively in ray-tracing, \(f_r(x, \omega_i, \omega_0)\) is a BRDF, and \((\omega_i \cdot n)\) is the cosine of the angle between the incoming direction and the surface normal.

To render a scene we shoot out primary rays from the virtual camera location through the center of each pixel. Subsequently, we find if, and where, these rays intersect the 3D scenes. At the points of intersection we calculate any reflections, refractions, or other physical effects. If the surface is reflective, a secondary ray is cast in the reflection direction (based on the law of reflection: the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection). The process is repeated recursively for this reflected ray. Typically, we estimate the integral over the hemisphere using Monte Carlo - it is common to shoot many rays, each with a slight noise, all going through the pixel. We then compute the rendering equation for all incoming rays and aggregate to obtain the color of this pixel.

The just-in-time compiler of Mitsuba traces the rendering process, resulting typically in a gigantic computation graph, compiles it to a monolithic megakernel, and then executes it. To take gradients it uses a clever algorithm called adjoint rendering, which traces light backward from the sensors (pixels) to the light sources allowing for efficient computation of gradients by solving an adjoint light transport problem. Thus, automatic differentiation in ray-tracing can be interpreted as its own kind of simulation. The camera effectively emits derivative light into the scene that bounces around and accumulates gradients whenever it hits a surface.

So what can we do with this differentiable physics-inspired rendering? We can solve problems like:

- Pose estimation: find the location and orientation of an object so it looks in a certain way,

- Caustics optimization: e.g., recovering the surface displacement (heightmap) of a slab of glass such that light passing through it focuses into a specific desired image,

- Polarization optimization: e.g. how should two polarization filters be placed sequentially so that light polarization renders in a certain way,

- Mesh estimation, e.g. how should an object's structure look like so that its shadow, when rendered using a perspective camera, looks in a certain way.

Overall, differentiable rendering is an exciting research field, with lots of practical applications in both graphics and computer vision. I'm quite amazed at the problems that people have already tried to solve with these approaches. And probably there are many more interesting things that I'm not even aware of...