Data-Driven Structure From Motion

Structure from motion (SFM) has come a long way. It started back in the 1950s when researchers painstakingly derived 3D structures from pairs of aerial photographs through precise geometric reasoning. The eight-point algorithm in 1981 was one of the first applications of mathematical rigour to the problem. In the late 1990s RANSAC enabled robust estimation in the presence of noise, while bundle adjustment greatly improved the reconstruction precision by jointly updating both the camera parameters and the scene geometry. In the next 10 years these solutions were scaled up and turned into products. Since then, deep learning has become the norm, with more of a focus on data-driven learning instead of explicit geometry modeling.

SFM is a huge topic and we cannot cover all the major developments in details. Instead, we'll only explore 5 particular papers from the Visual Geometry Group in Oxford, leading up to the VGGT.

Traditional two-view SFM. Suppose we have only two views. The classic approach for recovering camera motion (rotation and translation) and 3D geometry (sparse point cloud) is as follows:

- Detect keypoints and extract features for them using e.g. SIFT. Match keypoints from one image \(\mathbf{x}_i\) to keypoints in the other image \(\mathbf{x}_i'\), forming sparse matching points \((\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_i')\).

- Use RANSAC to filter the matching points. Concretely, randomly select 5 matching pairs (assuming known camera instrinsics \(\mathbf{K}\)) and estimate the intrinsic matrix \(\mathbf{E}\). Then compute the errors (epipolar constraint residuals) for all matched pairs using that essential matrix. Count the number of inliers - pairs with an error below a specified threshold. Repeat this whole random process of sampling pairs and estimating their essential matrix for a number of iterations, finally obtaining the essential matrix with most inliers.

- Decompose the essential matrix into a rotation matrix and a translation vector, \(\mathbf{E} = [\mathbf{t}]_\times \mathbf{R}\). There are 4 possible \((\mathbf{R}, \mathbf{t})\) solutions. Select the physically appropriate one based on the cheirality constraint, ensuring reconstructed points lie in front of both cameras. The essential matrix constraint \(\mathbf{x}_i'^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{E} \mathbf{x}_i = 0\) is satisfied for any scaling factor \(\alpha\) in the translation, \([\alpha \mathbf{t}]_\times \mathbf{R} = \alpha [\mathbf{t}]_\times \mathbf{R} = \alpha \mathbf{E}\), hence the retrieved translation is only up to a multiplicative constant (scale ambiguity).

- Use triangulation to estimate the 3D points. The 3D point \(X_i\) is chosen to be the one that minimizes the distance between the two rays - one from camera center \(C_1\) through \(\mathbf{x}_i\) and the other from camera center \(C_2\) through \(\mathbf{x}_i'\).

This classic approach is well-posed but produces relative camera motion and relative scene geometry, i.e. up to an unknown scale factor. With deep learning nothing prevents us from trying to predict absolute depth from a single image and absolute camera motion from both images. Yet, this is ill-posed and performance depends on how close the test image pair is to the training pairs, so that whatever priors are learned from the training set are still reasonable in the new images.

Deep two-view SFM. In 2021 an interesting approach was proposed that is both accurate, due to deep learning, and well-posed, due to incorporating classic SFM elements [1]. What they do is:

- Estimate the optical flow between the two images. This produces dense matching points which need to be heavily filtered. To do so, use SIFT just for keypoint detection (not matching). The optical flow is more accurate in high-textured regions found by SIFT.

- Apply RANSAC on the filtered pairs obtaining \(\mathbf{E}\) and therefore \((\mathbf{R}, \mathbf{t})\) after decomposition.

- For depth, however it is obtained, it should not be supervised with GT metric depth because this will introduce a mismatch between the relative translation \(\mathbf{t}\) and the predicted depth \(d_i\).

- Instead, use something similar to plane sweep stereo. For point \(\mathbf{x}_i\), its matching point \(\mathbf{x}_i'\) lies somewhere along the corresponding epipolar line. If you knew the depth \(d_i\), you can get the point as \(\mathbf{x}_i' = \mathbf{K}[\mathbf{R} | \mathbf{t}] [(\mathbf{K}^{-1}\mathbf{x}_i) d_i, \ 1 ]^\mathsf{T}\). But the translation \(\mathbf{t}\) obtained previously is only relative. So we do two things: first we normalize \(\mathbf{t}\) to unit norm, and second, we prepare multiple depth planes \(d_1, d_2, ..., d_D\). The plane sweep algorithm generates a cost volume of shape \((H, W, D)\) from which it retrieves the estimated depth of that pixel, \(\hat{d}_i\). It is then scaled according to the GT scale, \(\alpha_\text{GT} \hat{d}_i\) and is supervised with the GT metric depth. This is called scale-invariant matching and is well-posed. Phew...

Thus, we see how deep learning can tackle some aspects of the SFM pipeline, while well-known geometric aspects such as epipolar geometry can glue the individual steps into a unified whole.

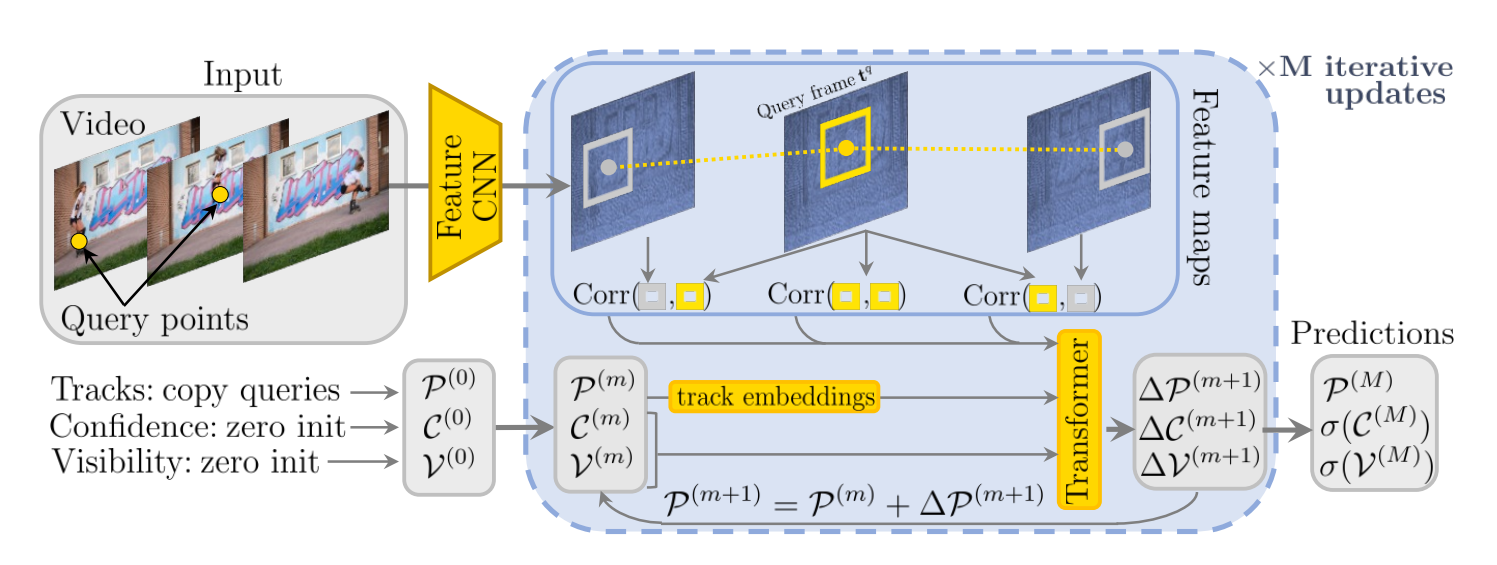

Tracking. Now, consider another task related to SFM which is point tracking. Here we'll take a look at the CoTracker3 model [2] which can reliably track points across long videos while handling occlusion. When working in an offline manner, it processes an entire video jointly and is memory-bound. In that setting tracking means that a query point \((x_q, y_q)\) is given from frame \(t_q\) and the goal is to find the track points \(\mathcal{P}_t = (x_t, y_t), \forall t \in \{1, ..., T\}\) across all \(T\) frames of the video which correspond to that query point. They are all initialized to the query point.

A CNN extracts multi-scale features from each video frame. We can describe each point by extracting a square neighbourhood of feature vectors at different scales around its location. And by dot-producting different point features we get feature correlations. This is how the query point can be compared to the track points. With \(N\) query points and \(T\) total frames we end up with a grid of tokens of shape \((N, T)\). This goes through a transformer which updates the track points, their confidences and visibilities \(M\) times.

How do you train such a beast? You collect a large set of unlabeled real-world videos and use multiple teacher trackers to label them. The initial query points are SIFT keypoints, because points in high-texture regions are usually easier to track. The tracks from the teachers become the supervisory signal with which the actual student network is trained.

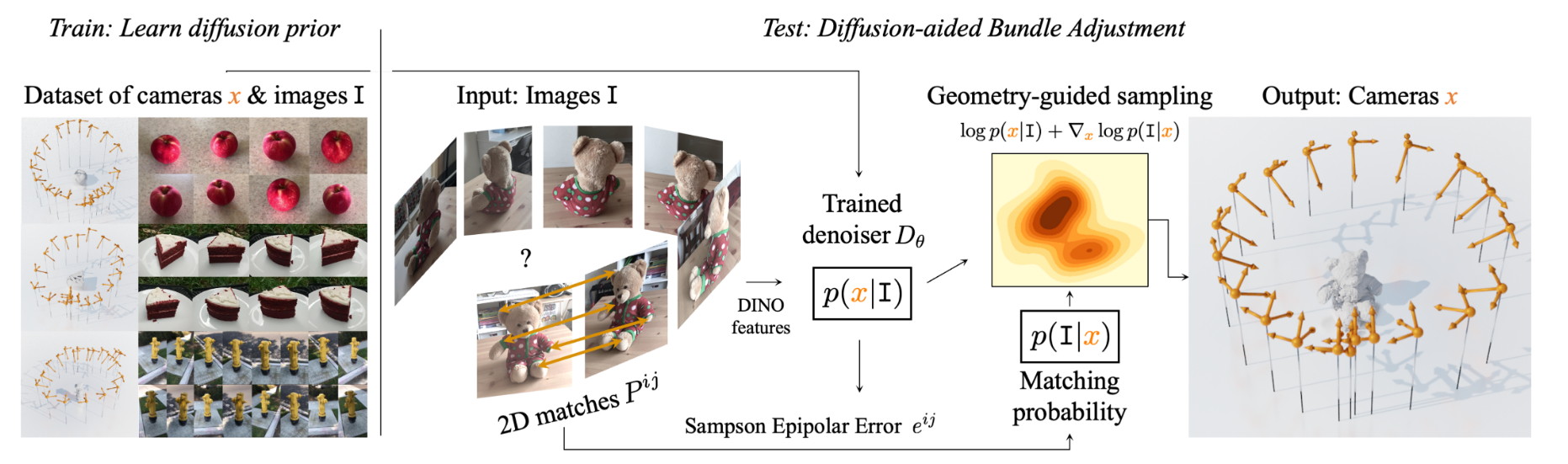

Estimating camera parameters. Another interesting paper is PoseDiffusion [3]. It deals with the problem of estimating the camera poses from a given number of images. The idea is quite straightforward - train a diffusion model to sample from \(p(x | I)\) where \(x\) are the camera parameters and \(I\) are the images. It is assumed that this distribution is sufficiently peaked so that any sample from it can be considered a valid pose.

Naturally, to train the denoiser, one needs a large dataset of scenes and camera poses \((x_i, I_i)_{i=1}^S\). Noise is applied only over the camera poses. The model learns to look at the images and iteratively denoise the camera poses. Once this is done, you can get pretty reasonable camera poses on novel, unseen scenes. Yet, there is more you can do. The epipolar constraints in any pair of two images can be used to constrain the distribution of generated camera poses conditioned on the images. This signal can be used to steer the denoising process in more favourable directions.

The epipolar constraint is \(\mathbf{x}'^\mathsf{T} F \mathbf{x} = 0\) for matching points \((\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')\). Yet, due to noise, it's rarely exactly zero. A very good robust approximation to this quantity is the Sampson epipolar error,

which is a first order approximation of the full reprojection error. The idea is that we'll steer the diffusion process towards camera poses with lower Sampson error:

Here \(\mathcal{D}(x_t, t, I)\) is the mean predicted by the denoising process, \(\hat{\mathcal{D}}\) is the guided mean, and \(e^{ij}\) is the Sampson error over the paired images \(i\) and \(j\).

Multiview SFM. How do we reconstruct structure from multiple views? The classic approach is cumbersome. It involves incrementally adding more and more images. We start with some pair of images for which we find the camera poses and the point cloud. Then incrementally add a new image, solve for its camera pose using PnP, triangulate the new 3D points, and periodically do bundle adjustment (BA), refining all camera poses and all 3D points.

The modern deep-learning equivalent of this is given by [4]. Reconstruction is achieved by tracking 3D points across all images at the same time, initial camera estimation, triangulation, and periodic differentiable bundle adjustment:

- Tracking is done by a transformer which takes \(N_T\) queries per image and outputs \((N_T, N_I)\) tokens, representing each of the \(N_T\) query points in each of the \(N_I\) images.

- Camera initialization is also done by a transformer that takes in global ResNet tokens and descriptors for the track points and cross-attend them together. It outputs camera parameters.

- Triangulation is done by another transformer that takes in the tracked points and a predefined point cloud which is refined towards the true 3D point cloud.

- Bundle adjustment refines both the geometry and the camera poses by minimizing a joint reprojection error.

The BA problem itself requires that you optimize the camera poses and the 3D points. Yet, your ultimate goal is to train the network to minimize your overall loss function. So the BA problem actually requires an inner optimization within each main optimization loop. We're interested in how the optimal poses and 3D points change as the weights \(\theta\) change. Differentiating through the inner optimization itself is very tricky. Libraries like Ceres or Theseus use the implicit function theorem to compute the required gradients.

As we've seen so far, more and more aspects of the classic SFM approach are being done through deep learning instead of visual-geometry methods. Some tasks, like feature matching and monocular depth estimation, cannot be solved by geometry alone. There, deep learning is absolutely needed. Yet, can we push it beyond that, to the point where all scene attributes of interest are estimated using feed-forward networks?

Data-driven reconstruction. The visual geometry grounded transformer (VGGT) [5] goes into this direction. It is a single transformer that uses a shared backbone with multiple branching heads to predict camera poses, depth maps, point maps, and tracks. Specifically, given \(N\) images of shape \((N, H, W, 3)\) the output poses are \((N, 9)\) representing quaternions, translations, and focal lengths, the depth maps are \((N, H, W)\), the point maps are \((N, H, W, 3)\) in the coordinate system of the first camera, and the tracks are actually track features of shape \((N, C, H, W)\) from which the point tracks are produced.

The transformer has 24 layers. It is a ViT patchifying all frames into tokens and using alternating global and local self-attention layers. In global self-attention each token attends over all other tokens, across all frames. In local self-attention it attends only to those tokens within the same frame. For the dense predictions they use a DPT head [6].

There is a certain amount of redundancy in the outputs. Camera poses can be inferred from the point maps, which can be inferred from the depth maps. Yet, having multiple over-complete predictions improves performance noticeably. It is up to the user to use decide which point cloud to use - the one from the depth head or the one from the point map head.

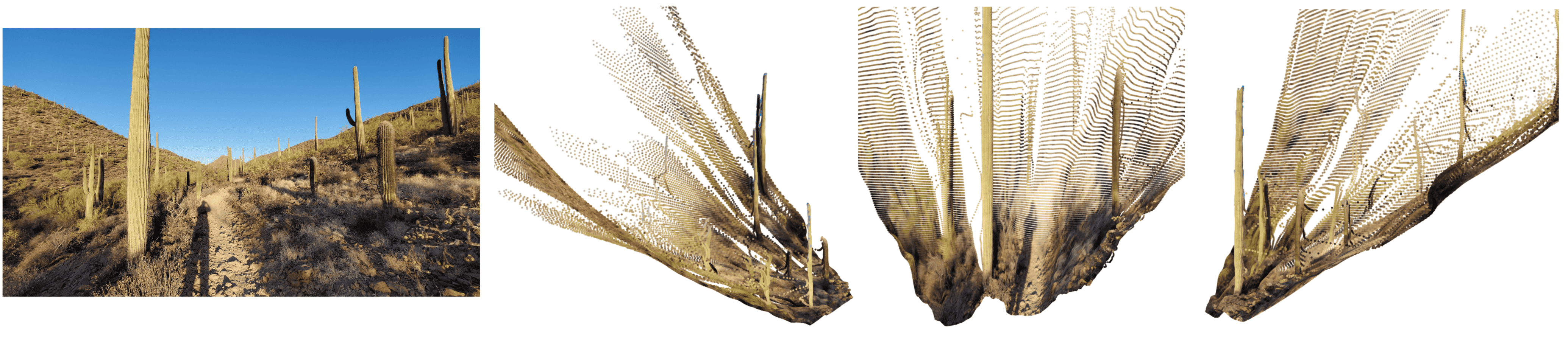

Naturally, when I tested the model I was impressed with the quality on their particular examples. The reconstructions seem accurate and clean. Yet, I found the performance on realistic complicated outdoor scenes to be far from perfect. Figure 2 shows an example. Note that VGGT resizes the images to a maximum dimension of 518 pixels, so reconstructions are blurry and lose details. Overall, they are okay-ish and can benefit from additional training on similar outdoor scenes. Nonetheless, it is clear that SFM is still far from solved.

References

[1] Wang, Jianyuan, et al. Deep two-view structure-from-motion revisited. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2021.

[2] Karaev, Nikita, et al. CoTracker3: Simpler and better point tracking by pseudo-labelling real videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.11831 (2024).

[3] Wang, Jianyuan, Christian Rupprecht, and David Novotny. Posediffusion: Solving pose estimation via diffusion-aided bundle adjustment. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 2023.

[4] Wang, Jianyuan, et al. Vggsfm: Visual geometry grounded deep structure from motion. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2024.

[5] Wang, Jianyuan, et al. VGGT: Visual Geometry Grounded Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.11651 (2025).

[6] Ranftl, René, Alexey Bochkovskiy, and Vladlen Koltun. Vision transformers for dense prediction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2021.