Information, Codes, and Content

Information theory is the subfield of applied mathematics concerned with topics like information content, data compression, information storage and transmission. The key terms and concepts appear often in machine learning and I have found myself sometimes cross-referencing them from both disciplines. In this post, we cover some of the absolute basics - entropy, some simple codes, and limiting results. I think these ideas integrate nicely with other fields and are useful as a general background context for machine learning. Even more so, they are fundamental, due to how learning is inherently related to data compression.

What is a bit? What is information? These questions are surprisingly abstract and difficult to formalize. Some philosophers are dedicating their entire careers on these concepts. For us, a good definition I've heard is: a bit is a single discernible difference. This difference is always between two comparable entities. It doesn't matter what they are - could be "yes" vs "no", "red" vs "blue", "likely" vs "definitely", "zero" vs "one" - these are all discernible differences. The elegance of defining the bit in such a way lies in its formal implication - it is defined purely by its function to distinguish, capturing any variance between two items, akin to how the numeral 5 can symbolize any collection comprising five elements. With two bits we can represent 4 different entities - for example "no", "somewhat", "almost", and "yes". With \(n\) bits we can represent \(2^n\) different states.

More generally, discernible differences exist also when it comes to unknown or random events. Even if we live in a deterministic universe, our beliefs about the current world state are limited and can be represented as probabilities - this being called the subjective interpretation of probability, as opposed to the frequentist one. In that case the objects of interest become random variables. And by virtue of the fact that random variables can have multiple discernably different outcomes, we conclude that the information of an outcome depends on its probability.

Suppose we have a random variable \(X\) with outcomes \(\mathcal{A}_X\) and a probability distribution \(p(x)\). The information content, or uncertainty, of a random outcome \(x\) is given by \(H(X = x) = -\log_2 p(x)\). The entropy of the whole random variable \(X\) is the average uncertainty of any one outcome,

It is non-negative and maximal when all outcomes are equiprobable. The information entropy and by extension the entropy is zero if the probability of the (only) outcome is \(1\). If the entropy is \(n\) bits, then observing any outcome gives us, on average, \(n\) bits of information. Some particular outcomes may give us more or less information.

In general an encoding is a function which maps outcomes to strings of symbols. For simplicity, we can think of it as taking a particular \(x\) and mapping it to a binary string called a code, e.g. \(011011\). If the mapping is isomorphic we can uniquely identify and distinguish each outcome based on its code. The length of the code is given by the number of bits it has. Typically we are interested in finding an encoding which minimizes the length of the average code, according to the probabilities of the random variable \(X\), while still being unambiguous and easy to decode. This will allow us to reduce data size of any data stored or transmitted. As we'll see soon, there is a fundamental limit on how short the average code can be without losing information.

Compressing data refers to encoding it in a way such that the total code length is less than the length of the unencoded data. One important criterium is average information content per source symbol. Suppose we have a source file and we encode it into a file with \(L\) bits per source symbol. If we can recover the data reliably, then necessarily the average information content of that source is at most \(L\) bits per symbol. Not all encodings compress the data. If there are \(M\) outcomes we can always encode them with \(M\) codes, all of the same length, each with \(\log_2 M\) bits. This encoding does not consider the probabilities and hence does not compress anything.

There are two types of compressors. А lossy algorithm maps all outcomes to shorter codewords, but some outcomes are mapped to the same codeword. As a result, the decoder cannot unambiguously reconstruct the outcome, which sometimes leads to decoding failures. Instead, a lossless algorithm maps most outcomes to shorter keywords. It preserves all information and shortens the codes of the most probable \(x\)-s but the rare ones have longer codewords, beyond the \(\log_2 M\) bits corresponding to the codelength when not compressing.

Let's consider lossy compression. For any \(0 \le \delta \le 1\), we can compute the smallest \(\delta\)-sufficient subset \(S_\delta\), satisfying \(P( x \in S_\delta) \ge 1 - \delta\). Intuitively, this set contains the most probable outcomes - those until their sum becomes greater than \(1 - \delta\). If one wants to be able to decode as many codes as possible, then the most common ones should be preferred and the subset \(S_\delta\) should be used. The quantity \(\delta\) is then the probability, set by us, that an outcome will not be encoded at all. If \(\delta\) is very high, most outcomes will not be encoded. Those that will be, will be very few, and hence the codes can be short overall. The quantity \(\log_2 | S_\delta |\) is called the essential bit content of \(X\), \(H_\delta(X)\). It gives the number of symbols needed to distinguish the most common outcomes of \(X\), with an accepted error of \(\delta\).

Next, consider \(N\) i.i.d. random variables like \(X\), \(X^N = (X_1, X_2, ..., X_N)\). We'll denote the joint sample as \(\textbf{x}\). The joint entropy is additive for independent outcomes and is \(H(X^N) = NH(X)\), for any one \(X\). But can we say anything about \(H_\delta(X^N)\)? For concreteness assume the outcomes \(\mathcal{A}_X\) are different symbols from an alphabet. Consider the "most typical" outcome of \(X^N\). \(X^N\) will likely contain \(p(x_1)N\) instances of the first symbol, \(p(x_2)N\) instances of the second symbol and so on. The information content of this typical string is precisely \(NH\). Slightly less typical strings will have information content somewhere around \(NH\). Based on this, we define the set of "typical" string samples - those strings whose information content per symbol is within a threshold \(\beta\) of the expected information content per symbol:

Here \(\mathcal{A}_X^N\) is the set of all joint outcomes. Naturally, the probability of any typical \(\textbf{x}\) satisfies \(2^{-N(H + \beta)} < p(x) < 2^{-N(H - \beta)}\) and hence, by the law of large numbers, along with Chebyshev's inequality, the probability that \(\textbf{x}\) is typical will become close to unity as \(N\) increases:

Therefore, as \(N\) increases, most strings \(\textbf{x}\) will be typical. This is a first observation. A second useful one is that we can approximately count the number of typical elements. The smallest probability that a typical \(\textbf{x}\) can have is \(2^{-N(H + \beta)}\). We need the total probability of the typical elements to be less than unity, \(| T_{N\beta}| 2^{-N(H + \beta)} < 1\) and hence \(| T_{N\beta} | < 2^{N(H + \beta)}\).

The typical set \(T_{N\beta}\) is not the best set for compression, \(S_\delta(X^N)\) is. For a fixed \(\beta\), \(S_\delta(X^N)\) necessarily has at most elements as \(T_{N\beta}\), so in fact the size of the typical set provides an upper bound on \(H_\delta(X^N)\). Hence \(H_\delta(X^N)\) is bounded from above by \(\log_2 | T_{N\beta}| = N(H + \beta)\). We now set \(\beta = \epsilon\) and choose some possibly large \(N_0\) such that \(\frac{\sigma^2}{\epsilon^2 N_0} \le \delta\). The result is that \(1/N \cdot H_\delta(X^N) < H + \epsilon\), which is independent of \(\delta\).

A proof by condradiction based on similar logic shows that \(1/N \cdot H_\delta(X^N) > H - \epsilon\), which is again, indepedent of \(\delta\). This result is quite deep and is called Shannon's source coding theorem:

Here's how to interpret it. We have a source of information - a random variable. We first fix the probability of error \(\delta\) that we are willing to accept. We might even fix it something arbitrarily close to \(0\). Now, the average minimal bits per symbol consistent with \(\delta\) are given by \(H_\delta(X^N)/N\). For any finite sequence of \(N\) samples, the required bits per symbol do not exceed \(H + \epsilon\). \(N\) and \(\epsilon\) depend on each other, so for a fixed length \(N\), we can calculate an \(\epsilon\) or vice versa, for a desired \(\epsilon\) we can calculate a required \(N\). As \(N\) tends to infinity the bits per symbol of the encoding cannot increase beyond the entropy. Likewise, one needs at least \(H-\epsilon\) bits per symbol to specify \(\textbf{x}\), even if we allow errors most of the time. Therefore, this result establishes that for lossless compression the average optimal code length cannot be shorter than the entropy.

Therefore, the entropy \(H(X)\) obtains а new meaning. It gives a lower bound on the average bitlength of a lossless encoding of \(X\). The cross-entropy, \(H(p, q)\), used commonly in machine learning, also has an interesting meaning. Through the cross-entropy decomposition

one can see that it gives a lower bound on the average bitlength when one is coding the distribution \(q(x)\) rather than the true one \(p(x)\). Similarly, the KL divergence gives precisely the difference between the codelength when coding for \(q(x)\) and when coding for \(p(x)\).

The source coding theorem tells us that near-optimal codes exist, but it does not tell us how to find them. It also encodes entire blocks of symbols. Symbol codes are variable-length codes which are lossless and encode one symbol at a time. To encode a whole message \(x_1 x_2 ... x_N\) we simply concatenate the codes \(c(x_1)c(x_2)...c(x_N)\). Ideally these codes should be uniquely decodable, which requires that no two symbols have the same encoding. Moreover, it should be easily decodable. This is achieved when no codeword is a prefix of any other codeword. This implies that one can read the codemessage left-to-right and decode as they go, without looking back or ahead of the current codeword. Such codes are called prefix or self-punctuating codes. Lastly, to achieve maximum compression, the average codelength should be minimal.

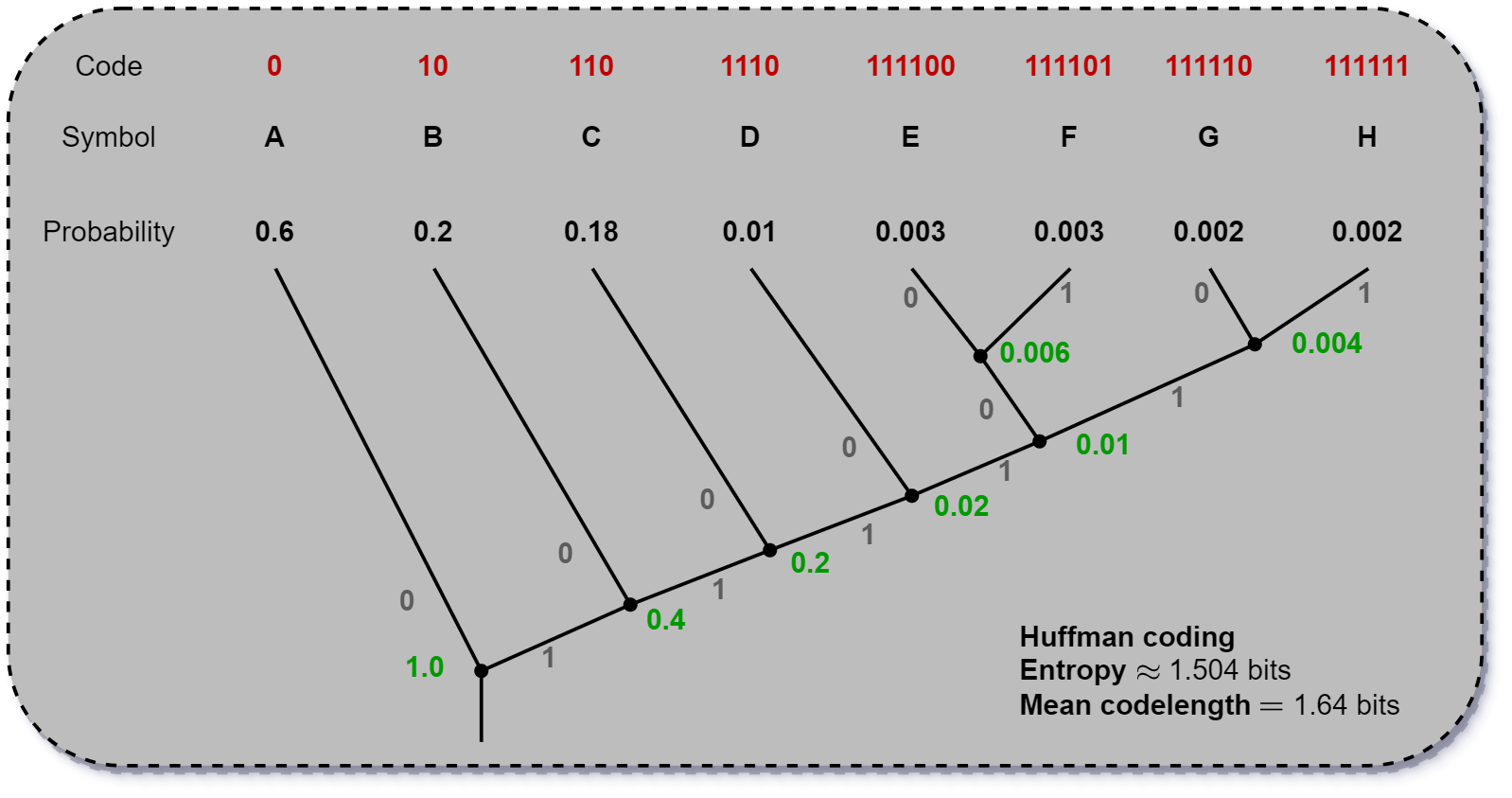

There are some useful results for symbol codes. First, the Kraft inequality states that if a code is uniquely-decodable, then its lengths satisfy \(\sum_{x \in \mathcal{X}}2^{-l(c(x))} \le 1\), where \(l(\cdot)\) is the length operator. If the codes satisfy this inequality, then there exists a prefix code with those lengths. Moreover, the optimal source codelength satisfy \(l_i = -\log_2 p_i\) and similarly to the source coding theorem, there exists a prefix code for \(X\) satisfying \(H(X) \le L(C, X) \le H(X) + 1\). The Huffman coding is an optimal variable-length prefix symbol code.

Compared to symbol codes, stream codes represent the data as a stream of possibly non i.i.d tokens and adapt the encoding accordingly. Arithmetic codes are efficient stream codes and are currently one of the go-to solutions for lossless compression. For notation, we have a sequence \(x_1, x_2, ..., x_N\) where \(x_i\) is the \(i\)-th random variable and \(a_i\) is the particular observed symbol from it. The symbol alphabet has \(I\) symbols and \(a_I\) is an end-of-sequence (EOS) token. Suppose we have access to a probabilistic model for \(p(x_i = a_i | x_1, x_2, ..., x_{i-1})\). Arithemtic codes work by modeling intervals within \([0, 1)\). Consider that we can always divide \([0, 1)\) into \(I\) intervals according to \(p(x_1)\). Then, depending on the exact value of \(x_1\), suppose \(a_i\), we can take its interval and divide it again in \(I\) intervals. Let's denote the \(j\)-th new interval as \(a_{i,j}\). Its length will be precisely

Binary codes can be associated with intervals. For example, the code message \(01101\) is interpreted as the binary interval \([0.01101, 0.01110)_2\) which corresponds to the decimal interval \([0.40625, 0.4375)\). To encode the full string \(x_1x_2...x_N\) we compute the interval corresponding to it and send any binary string whose interval belongs fully within this interval. The actual encoding happens symbol by symbol and whenever the current interval falls within the previous estimated ones, the encoder can produce the next bit. The decoder works similarly, it uses the model to estimate the bounds of the various next intervals and decodes the next symbol as soon as the observed interval falls within one of them. It can also generate samples by starting from random bits, similar to various deep learning models.

Lempel-Ziv codes are another useful type of stream codes which do not need a probability model for the underlying data. They works by memorizing sequences of substrings and replacing subsequent encounters of these substrings with pointers to them. They are universal, in the sense that given an ergodic source these codes achieve asymptotic compression down to the entropy per symbol. In practice, they have proved useful and have found wide applicability in tools like compress and gzip, although various modifications of the algorithms are typically used.

None of these codes will be decoded properly if any of the message bits are changed. Thus, in a noisy channel, where the environment can mutate the codes before they have been passed to the decoder, one needs to be careful - error detection and correction algorithms are needed.

A discrete noisy memoryless channel \(Q\) adds noise to the codewords and is characterized by an input and output alphabets \(\mathcal{A}_X\) and \(\mathcal{A}_Y\), along with the probabilities \(p(y | x)\). We can measure how much information the output \(Y\) conveys about the input \(X\) using the mutual information \(I(X; Y)\) defined as:

The mutual information \(I(X; Y)\) depends on the input \(X\) which is under our control. Hence one can find that particular distribution \(\mathcal{P}_X\) that maximizes the mutual information. The resulting maximal mutual information is called the channel capacity \(C(Q)\) and plays a crucial role in limiting the amount of information that is transmitted through the channel in an error-free manner.

As an example of some noisy channels consider the following:

- A binary symmetric channel randomly flips a given bit irrespective of its current value

- A binary erasure channel randomly deletes some bits, producing a new token like "?"

- A noisy typewriter channel randomly maps one outcome to its nearest neighbors. E.g. it may map the symbol B to either A, B, or C.

The channel coding theorem, again due to Claude Shannon, states that, intuitively, given any noisy channel, with any degree of data contamination, it is possible to communicate information nearly error-free up to some computable limit rate through the channel. This computable limit is given by the channel capacity. It is very easy to confirm the theorem for the noisy typewriter channel. Suppose the underlying alphabet \(\mathcal{A}_X\) is the English alhabet, with symbols \(A, B, C, ..., Z, \square\), where \(\square\) is the EOS symbol. Now, if you only use 9 symbols - \(B, E, H, ..., Z\), any output can be uniquely decoded because these input symbols constitute a non-confusable subset. The error-free information rate of this channel is \(\log_2 9\) bits, which is exactly the capacity.

Something interesting happens if we are allowed to use the noisy channel \(N\) times, instead of just once - the multi-use channel starts looking more and more like a noisy typewriter one (stated without proof) and we can find a non-confusable input subset with which to transmit data error-free. Indeed, the number of typical \(\textbf{y}\) is \(2^{NH(Y)}\). The number of typical \(\textbf{y}\) given a typical \(\textbf{x}\) is \(2^{NH(Y | X)}\). Hence, the non-confusable subsets are at most \(2^{NH(Y) - NH(Y | X)} = 2^{NI(X;Y)}\). This shows that for sufficiently large \(N\) it is possible to encode and transmit a message with essentially null error up to some rate given by the channel capacity.

These results are strong but they are only scraping the surface when it comes to codes. Some of the most powerful codes like low-density parity-check codes, convolution codes, and turbo codes build on top of more theory and hence we have to leave them for the future.