Attempts to Solve a Market

I was recently tinkering with some fairly realistic oligopolistic market simulations. Compared to textbook cases, where it is common to assume the market matches all buyers to all sellers simultaneously, in my case the simulation involved non-clearing markets, sequential search, and various computational constraints among the market participants. If you think about it, it gets quite hard to solve the market in this case. Analytic solutions are out of the question. One typically has to use numerical methods. Yet, I had the beautiful idea of tryin out multi-agent RL for finding the equilibria. It turned out to be a very nice bridge between the two disciplines - one providing the problem setting, and another providing the tool to solve it.

Background

Let's motivate the problem by building toward it from the ground up. We'll recap consumption and production, and then build the mathematical structure of the market.

Consumption. Consumers have preferences over world states. They can be expressed as binary relations between different bundles of goods. E.g. if the world state in which one has \(q_1\) units of good A and \(q_2\) units of good B is preferred over \(q_1\) units of good B and \(q_2\) of good A, we can denote this as \((q_1, q_2) \succeq (q_2, q_1)\). Here the quantities are what matters.

Now, under various important assumptions, called the axioms of rational choice, these preferences are captured by a cardinal utility function. Its values are meaningless, yet it accurately captures the same preferences, so we might say that \(u(q_1, q_2) \ge u(q_2, q_1)\). If people are rational, they would maximize this expected utility.

Consumption is about choosing how to best allocate scarce resources to maximize your immediate utility. For example, suppose a consumer has total income \(Y\), and there are only two goods, with prices \(p_1\) and \(p_2\). Then, the consumer has to decide how much \((q_1, q_2)\) to consume of both goods so as to maximize his utility \(u(q_1, q_2)\) while not going over his budget \(Y\). He faces the problem.

A common utility function is Cobb-Douglas which has realistic properties such as negative second derivatives representing diminishing marginal utility. When the consumption problem is solved, one obtains the optimal \(q_1^\ast(p_1, p_2, Y)\) as a function of the prices and the income, and the same for \(q_2^\ast\). Note that if we trace how \(q_1^\ast\) changes as \(p_1\) changes, we get the demand function.

The demand is important because it shows how many units \(q\) of a good are demanded at a given price \(p\). Likewise, if we invert it, the inverse demand \(p_1(q_1^\ast)\) shows the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay (WTP) for an additional unit of the good. To get the aggregate demand of the whole market we simply sum the quantities demanded at every price.

Production. On the other side of the consumers are producers that supply products. Producers have a production function \(q = f(L, K)\) where \(L\) and \(K\) represent the labour and capital inputs, respectively. Different combinations of inputs produce different quantities \(q\) of the product. Additionally, there are factor cost associated with \(K\) and \(L\) - wages \(w\) and rent \(r\), respectively. Thus, the cost of producing at \((L, K)\) is given by \(C(L, K) = wL + rK\), where we assume factor prices \(w\) and \(r\) are constant.

Producers face two important dual problems. They can either minimize cost given fixed \(q\), or maximize \(q\) given fixed cost. Consumers also have a dual problem similar to the one described above, which minimizes the expenditure given a constant utility. For the producers, the primal (on which we'll focus here) is the cost minimization problem: determine the inputs \((L, K)\) at which producing exactly \(q\) units yields minimum cost:

Evaluating the cost at \((L^\ast, K^\ast)\) yields the minimum cost \(C(q)\) needed to produce \(q\) units, which depends on \(q\), \(r\), and \(k\). Now what remains is to determine the value produced \(q\).

Perfect competition. In perfect competition, which is an idealized market model, firms are price takers. They maximize profit \(\pi\) by setting the quantity \(q\) so that

Thus, each firm sets the quantity to that point where its marginal cost \(dC(q)/dq\) is equal to the constant market price \(p\). Let's motivate this result a bit. What does it mean for a firm is a price taker? It means that it cannot influence the price. Whatever quantity it sets, the price is constant. Тhe demand is horizontal at the market price \(p\) and firms can sell as much as they want at that price. For that reason, if they produce a quantity \(q\), their revenue will be \(pq\). If a firm sets the price higher than \(p\), it will sell zero. If it sets it below \(p\), it will sell as much as it will sell if the price is \(p\).

To derive the supply curve one can trace how the selected quantity \(q^\ast\) depends on the price \(p\). Hence, the supply is given by \(q_s = [dC(q)/dq]^{-1}(p)\), and only whenever \(p\) is greater than the average cost curve (otherwise, it's more profitable to shut down). The total supply is given by the sum of all quantities supplied by the individual firms. Markets clear because however much is produced, is also bought. There are other complications which we'll skip.

Monopoly. A monopolist is a price setter - he is able to set any price \(p\) he wants. If he sets a price \(p\), the market demand is \(Q_d(p)\) so that's how many sells he can get. Thus, he will produce exactly that many in terms of quantity \(q\). The problem becomes

The last line shows the profit maximizing equation where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Further reshuffling yields the Lerner index, a useful formula showing that the monopolist sets the price above the marginal cost and the markup is inversely proportional to the demand elasticity.

Note the hidden assumption of perfect information. The monopolist needs to perfectly know the demand \(Q_d(p)\) at price \(p\), so he can produce exactly that much in terms of quantity, \(q_s = Q_d(p)\). This makes the market clear. If we remove that assumption then the monopolist has to set the quantity supplied \(q_s\) separately - a situation in which he may end up with not enough production or with leftover inventory:

This is a more general setting which allows for rationing. If \(q_s > q_d(p)\), then the monopoly will produce more than the market demands. If \(q_s < q_d(p)\) then the monopolist reduces the number of transactions below the desired ones. Note also that there is no clearly defined supply function here. There is only a supply point since the monopolist sets both the price and the quantity.

Problem Setting

Let's move to more realistic settings involving market friction. This is any factor that introduces transaction fees, product search, price dispersion, buyer-seller matching, or a myriad other phenomena. In our case instead of assuming that buyers and sellers are matched instantaneously, we'll build a very simple order book inspired from the workings of stock market exchanges.

So, consider a market where there are \(N\) firms and \(M\) consumers. Each of the consumers has a downward sloping linear demand function, whose precise parameters are chosen randomly. Trading happens day by day. Firm \(i\) sets its price \(p^i\) and quantity \(q_s^i\) for each day. The quantity \(q_s^i\) becomes the available inventory for that firm to sell during the day. We simulate a trading day by iterating over \(K\) transaction opportunities. Within each iteration a random buyer is selected. Then, we filter the firms by considering only those firms that have positive inventory (have something to sell), and whose set price is lower than the willingness to pay (WTP) of that buyer, evaluated at their prices. Then, out of all remaining firms the buyer chooses the one with the lowest price. If the buyer will not go over his average (across the prices) quantity demanded by buying one more unit, a transaction happens. We decrease the inventory of that firm by 1, increase its sales by 1, and increase the quantity bought by that buyer by 1. The trading day halts earlier if all sellers have empty inventories or if their prices are above any of the WTPs of the consumers.

After the \(K\) iterations, the firms have accumulated their sales \(n^i\) and can calculate profits simply as \(n^i p^i - C(q_s^i)\). We assume firms have linearly increasing costs \(C^i(q) = c^iq\). Thus, they have constant marginal costs but at different levels \(c^i\).

This is how we'll model the market process. At the end of each day it provides the number of sales \(n^i\) for each firm. The function \(n^i(p^i, \mathbf{p}^{-i}, q^i, \mathbf{q}^{-i})\) depends on all prices and quantities and is discrete in values. It is also random and not differentiable. The problem of the firm \(i\) is

What does it mean to solve the market in this case? This objective has to be solved for all firms simultaneously. But since the \(N\) firms are sharing (partitioning) the market through their sales, this becomes a strategic game involving different interactions. A transaction for one firm is a lost transaction for another firm. Thus, we're in the area of multiobjective optimization, where each firm has its own objective.

What does the solution look like? Generally, one object of interest is the Pareto frontier which contains all the price-quantity tuples that are non-dominated. A setting \((p^i, q_s^i)\) is non-dominated if firm \(i\) cannot increase its profit \(\pi^i\) without hurting the profit of another firm... Yet, this is not what we want. In our case firms will gladly increase their profits at the expense of other firms. We're actually looking for a Nash equilibrium. It represents a point \((p^1, q_s^1, ..., p^N, q_s^N)\) such that the profit \(\pi^i\) of firm \(i\) is maximal with respect to \((p^i, q_s^i)\) if all other firms set their price-quantities precisely to \((\mathbf{p}^{-i}, \mathbf{q}_s^{-i})\). The same is simultaneously valid for them. A maximal profit in this case means that you don't have incentives to deviate. Thus, the Nash equilibrium represents a point of convergence from which no firm has any incentive to deviate. It is a fixed point with respect to the dynamics of the system.

Proving whether a Nash equilibrium exists and whether it's unique is tricky. There are various theorems. Let's avoid this question altogether. Assuming it exists, the way to find it is by first computing a best-response function for each player. It simply returns the best action for each player, assuming a given set of other actions for the other players. In our setting for player \(i\) it is \(\text{BR}(\mathbf{p}^{-i}, \mathbf{q}^{-i}, c^i) = \text{arg}\max_{p, q_s} \pi^i(p, \mathbf{p}^{-i}, q_s, \mathbf{q}_s^{-i}) = (p^\ast, q_s^\ast)\). It computes the best price-quantity for firm \(i\) given that the other price-quantities are \((\mathbf{p}^{-i}, \mathbf{q}_s^{-i})\). Once we have all BR functions we need to find their intersection which is the Nash equilibrium. This can be done through an iterative approach where we start from a random set of price-quantities and we evolve them according to the BRs until they converge.

Multi-Agent Policy Gradients

I've implemented the market making process as a basic Jax function that takes in \(p^1, q_s^1, ..., p^N, q_s^N\) and returns the profits and sales. I've then conveniently vmap-ed it to work with batches of prices and quantities. Let's see how the profit behaves in the case of only one seller and one buyer. The cost is linear, \(C(q) = cq\), with \(c=1.5\) and \(Q_d(p) = \max\{a - bp, 0\}\) with \(a=118\) and \(b=4.8\).

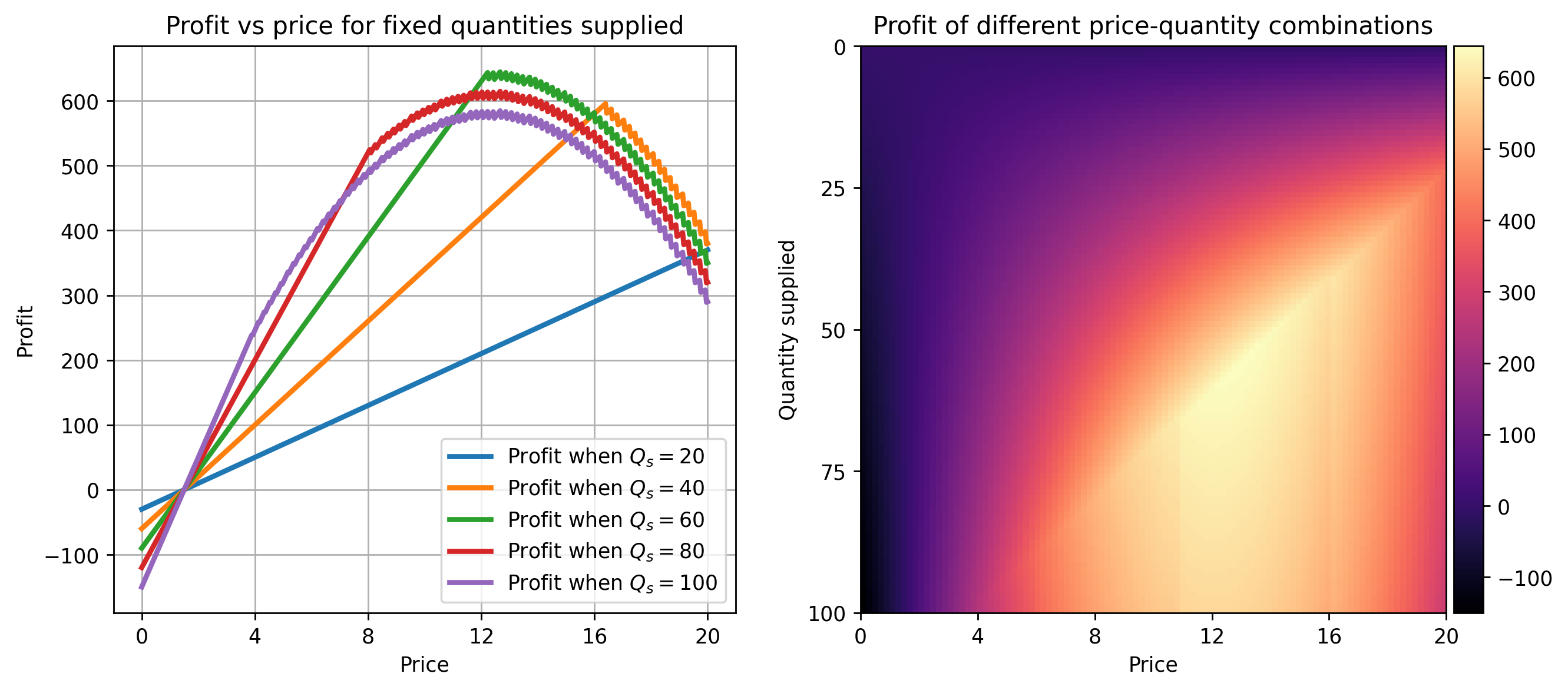

Figure 1 show the profit profile. There are a lot of things to unpack:

- In the right plot, the highest profit occurs when the price is around \(13\), which is consistent with the analytic solution of \(p^\ast = a/(2b) + c/2\).

- If the firm produces too much above the quantity demanded, its profit falls.

- In the left plot, consider how the profit depends on the price when \(q_s = 60\) (green). Up to a price of about \(12\), profit increases linearly and the number of sales is equal to \(q_s = 60\). Beyond that price the consumer starts demanding less than \(60\) units which bounds the sales. Depending on \(q_s\) a further increasing price could or could not increase the profits.

- There is a non-differentiable \((p, q_s)\) ridge caused by the \(\min\) operation. The global optimum is found on this ridge so convex optimization may not be easy.

- The spikiness after each kink in the lines of the left plot could be safely ignored. It likely results from the rounding of the floating points.

These plots make sense. Now, let's use a policy gradients agent to optimize for the right \((p, q_s)\). It works as follows. A very small single neural network will model the best responses for all sellers. The inputs to the network are \((\mathbf{p}^{-i}, \mathbf{q}^{-i}, c^i)\) and the outputs are \(\mu_p^i, \mu_q^i, f_p^i, f_q^i\). Hence, which inputs are passed to the network determines for which firm the output corresponds. First we scale the std features to within the range \([0, R]\), obtaining \(\sigma_p^i\) and \(\sigma_q^i\). Then we sample latent values for \(p\) and \(q\) and scale them to the ranges \([0, R_p]\) and \([0, R_q]\). Squashing happens with a sigmoid \(\sigma(\cdot)\).

The crucial hyperparameter here is \(R\) - it controls the noisiness of the actions. A higher \(R\) makes exploration easier and you can converge to the right answer faster. However, it also makes gradients potentially very noisy, to the point where learning becomes impossible. Hence, a very small value such as \(0.02\) is adequate. It stabilizes training at the cost of reduced exploration, which in turn can make convergence to a local minimum more probable.

After we get the actions for all firms, we execute the market environment and obtain the profits. Since all of this can be vmap-ed we can get a batch of profits at the same time, of shape \((B, N)\). Then, we compute the loss as \(-\mathbb{E}_{\mathcal{M}}[\log p_\theta(p^i, q_s^i | \mathbf{p}^{-i}, \mathbf{q}^{-i}, c^i) \pi^i ]\) for firm \(i\), where \(\mathcal{M}\) is the distribution of the market. We compute the Jacobian (not the gradient) of the profits and backbpropagate all the way back to the network parameters. Basically we obtain per-sample and per-seller gradients and average over these two dimensions. This effectively trains the network using \(N\) objectives.

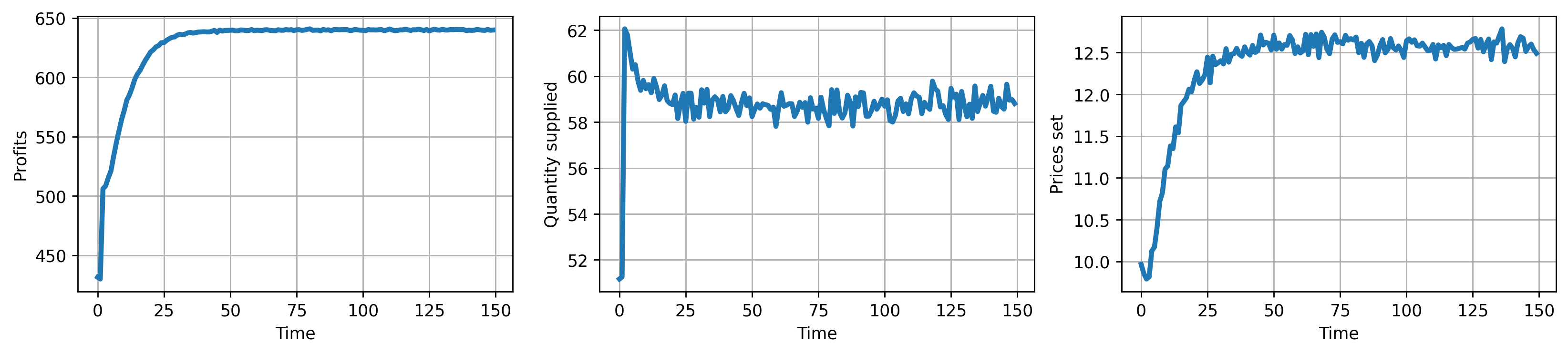

As a sanity check, we first solve the monopolist case with a single consumer. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of the price and quantity. Overall, the policy gradients in this case easily converge to a very good minimum, within 0.8% of the global minimum in terms of profits. Here we use simple SGD with Nesterov momentum.

Now that we know that our optimizer works in the verifiable simple monopolist setting, let's run it on a more serious problem - 10 consumers and 2 sellers with different marginal costs. In general, things can get complicated.

- If buyers always choose the seller with lowest price, the market often becomes a winner-take-all scheme. The firm with lowest prices sells the most and has the highest profit. Other firms are able to sell only if they lower their prices below the current firm's price. Profit swings rapidly from one firm to another. Equilibrium is found in sharp regions of the \((p, q_s)\) space.

- Similar sharp profit boundaries exist also if one of the firms commits to a given \((p, q_s)\). In that case, these values become a sharp point around which the other firm pivots.

- If buyers tolerate a small margin \(\xi\) above the minimum price and choose a seller randomly from those whose prices are within that margin, then profits tend to be split across the participating firms. Yet, if one firm commits to some \((p, q_s)\) which "stands in the way" of the other firm, a sharp boundary at a distance \(\xi\) from that price may form again.

- Optimization is hard. Suppose firm 1 has a competitive price \(\bar{p}\) and claims the whole market. Then firm 2 will have a very sparse revenue signal. Its sales will be null whenever its price is above \(\bar{p}\). If there is no gradient, or if it's too weak, the best response cannot be optimized.

- If buyers choose sellers probabilistically, inversely proportional to their prices, the sharp boundaries become more smooth, making optimization slightly easier, at the cost of introducing stochasticity in the results.

I ran many simulations with the policy gradients but am not convinced that they converge to something that can be called a Nash equilibrium (NE). Instead, a new question emerges - does a NE in pure strategies even exist for this market? We'll investigate visually.

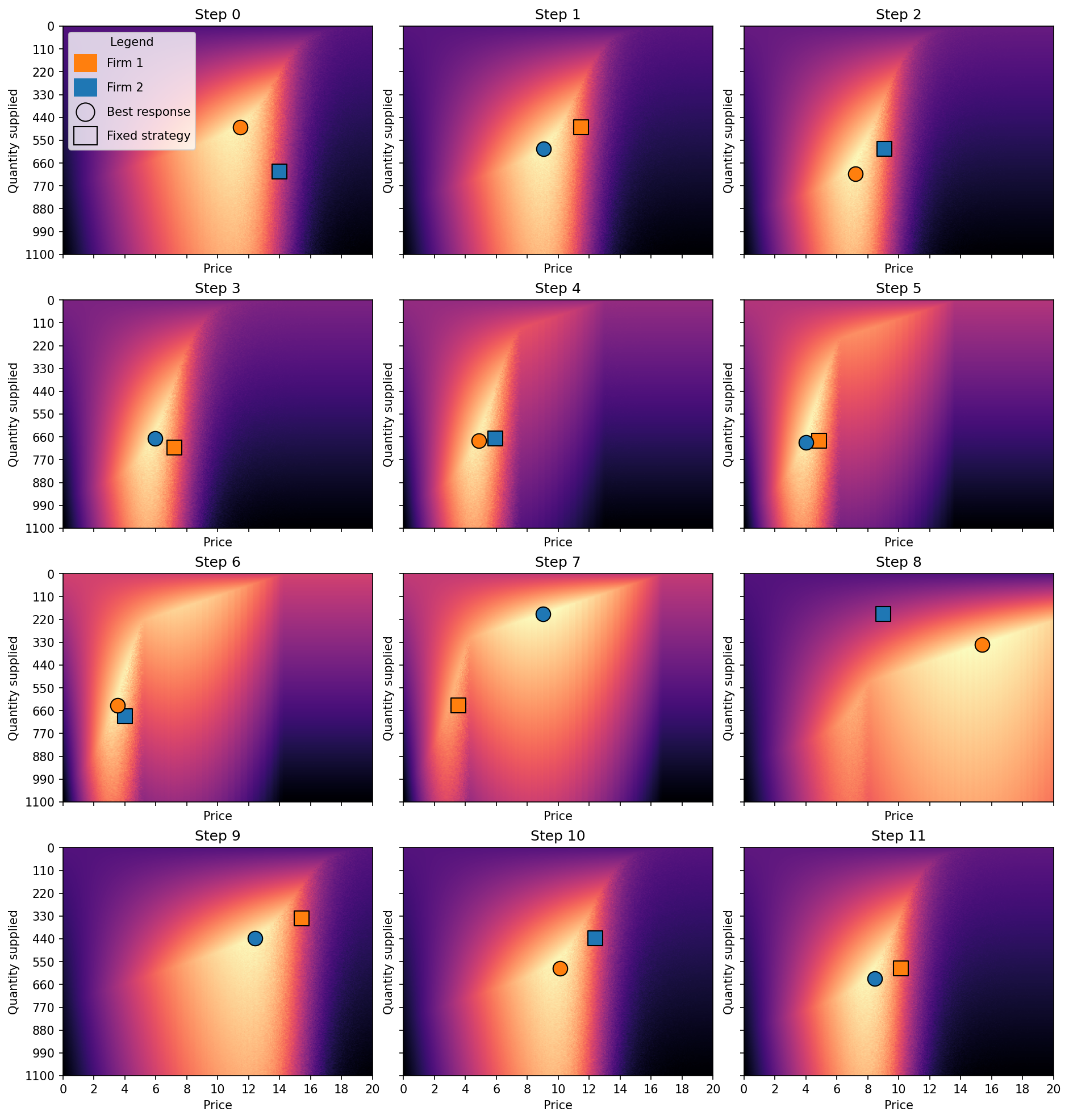

Fig. 3 shows the best response dynamics. Step 0 represents the profit landscape of firm 1 given an initial fixed \((p, q_s)\) combination for firm 2 (blue square). Firm 1 sets its \((p, q_s)\) to the orange circle. In step 1 firm 2 responds to this move by setting its combination to the blue circle. In step 2 firm 1 responds to the response by selecting the orange circle. And so on. An equilibrium occurs if two combinations converge and stop moving. Yet this does not happen.

In particular, it is often beneficial for one firm to undercut the other. At medium to high prices the firms undercut each other, pushing both prices and profits downward, similar to the prisoner's dilemma. Eventually one of the firms decides to reduce its quantity and increase its price, capturing these consumers with higher WTP. The other firm then follows this strategy and prices jointly increase again. This repeats, most likely ad infinitum.

Thus, we see that the dynamics of oligopolies are complicated, especially in more realistic market settings. Even though we couldn't "solve" this market, we got a lot of insights into the nature of the problem, which is still useful and rewarding.