An Austrian Perspective

Like virtually all aspects of our daily lives, there are many patterns hidden in our behaviour. Very few of our habits and activities are truly random. Hence, if we collect almost any data, we'll most certainly find useful patterns and regularities in it. The world which we have constructed is very regular and this has facilitated fields like data science to spread out and grow across all domains like mushrooms after rain.

Take history as an example. One source of data is historical accounts by ordinary people, as well as by scholars and professional historians. Of course, there are many official documents which make the data objective and accurate, but this is not the case for the ancient and medieval periods, where we often rely on personal accounts or historical interpretations. Exact documents like bills, decrees, and contracts are optimal because they provide the information as is. But historical accounts, as told by historians or commoners, can be biased. As a result, there may be a lot of noise in the data. Reconstructing history based on noisy data is like learning from an inconsistent teacher.

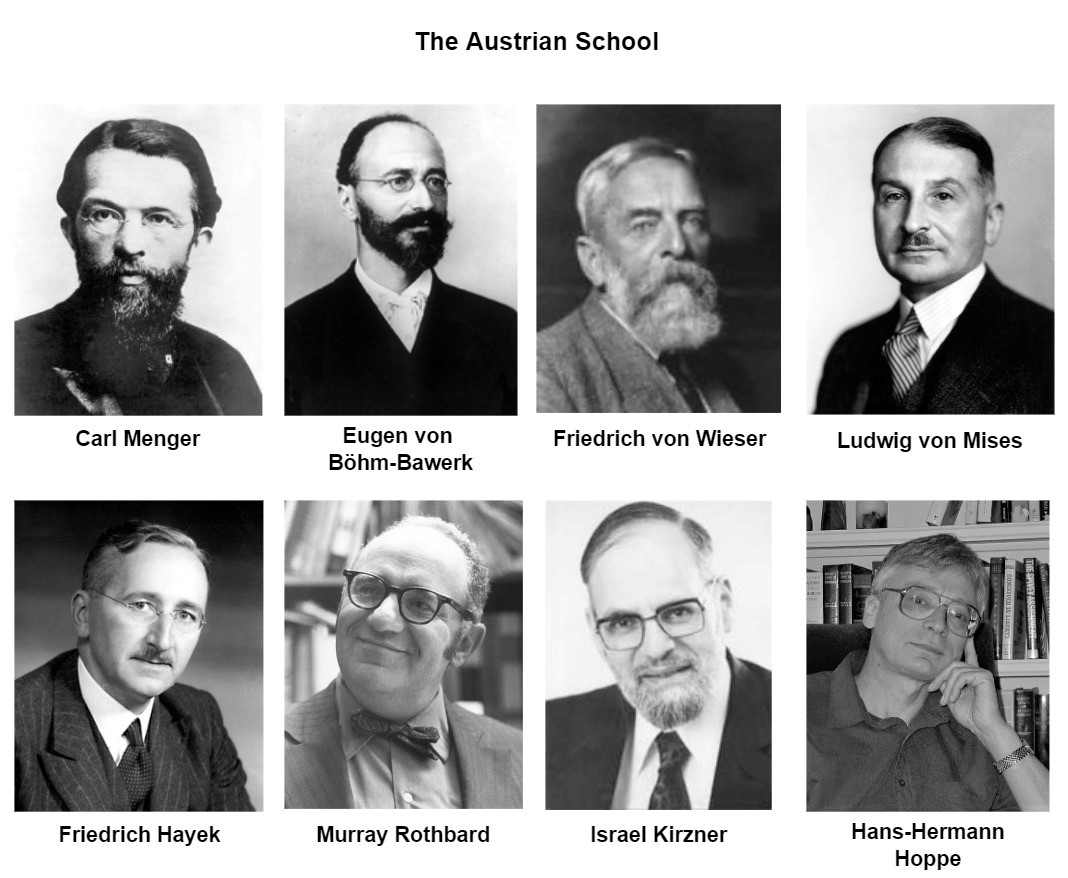

There are revisionist approaches which try to re-tell history based on both noisy accounts and noiseless principles. These principles often take the form of economics-based logical statements or philosophical axioms which can guide the interpretation of historical accounts. This post explores and summarizes professor Hoppe's essay From Aristocracy to Monarchy to Democracy - a critical look at how governments have evolved from ancient history to present day. It's an uncompromising rational explanation that hits hard, right where it needs to. Everything that follows is a paraphrase from the book.

Goods are scarce. There can be only a finite number of them, usually much lower that the number of uses and wants that people can place on them. As a result, interpersonal conflicts are inevitable. They are a constant threat to peace. And since dealing with these conflicts in a violent manner is costly, rational people need to come up with a peaceful resolution to such conflicts.

Some of the proposed solutions are more "just" than others. As an example, party A may propose to party B that whenever a conflict based on economic scarcity arises, irrespective of whether party A is directly involved in it or not, party A will be the ultimate arbiter to the conflict. Would party B agree to this? No, because this will allow party A to provoke a conflict and rule in its own favour. It will be equivalent to party A capitulating its claims to any current and future goods in conflict. Yet, this situation is our current reality when we take party A to be the State:

- The state has the right to tax you, effectively determining what amount of your private property you can keep

- The state can legislate, thereby controlling how you should live your life

- The state can have you killed, and under this conflict resolution scheme you cannot protest.

So how could such an institution like the State have come into existence? This has happened gradually across the centuries as governments transitioned from aristocracy through monarchy and to democracy. And the resulting story is one of economic folly and decay, not progress. In fact, the immense increase in social wealth and general standards of living have occurred in spite of these transitions, not because of them... and would have been much larger had they not occurred.

If people would not naturally accept the solution of the state, what would they accept? One option they would accept is the following:

- Everyone is the owner of all goods that they already, and so far undisputed, possess and control. Ownership implies the right of exclusive control.

- If a party A claims that they have previously owned a good currently belonging to party B, and that party B has taken this good without their consent, i.e. by theft, and if party A can demonstrate this, then ownership of the good reverts back to party A.

- The use or modification of a good by party A, but owned by party B, is allowed only if there is a contract between party A and party B stating so.

Adopting these rules by universal agreement will trivialize the solution of scarce goods conflicts, in that parties will only have to agree on the facts of the case. Likewise, the need for judges will not be a need for law-making, but rather of fact-finding. The insight here is that laws are not to be made, but discovered. They emerge naturally as accepted ways to solve conflicts. The role of the judge is only to apply the given law to the established facts.

Now, in any society of even minimal complexity, hierarchies form. They are based on the competencies of individuals for solving various tasks. It is natural that due to the intellect, knowledge, or wisdom that certain individuals possess - kings, nobles, natural aristocrats - they climb to the top of these hierarchies and become well-respected and sought-after for their opinions and capabilities. They are the people to whom the conflicting parties will turn to. Therefore, it is the aristocracy which become judges, simply because they are ruled to be the best and fairest when it comes to applying the discovered laws.

Importantly, if the king, or generally the aristocracy, does not make laws, but only applies them, then he does not have a legal monopoly on his position. Even if everyone turns to him, all conflicting parties are free to select another judge, if they question his judgement.

It can be claimed that at some point during the early European Middle Ages, a social structure similar to this type of aristocracy came into existence. While the allodial feudalism did have serfdom, when it comes to law, it can be characterized by the following favourable traits:

- Everyone was subordinated under one law,

- There was an absence of any law-making power,

- There were no monopolies of judgeship and conflict arbitration.

Unfortunately, this kind of social order did not survive for very long. Towards the end of the Middle Ages the formerly feudal king would insist that he become the ultimate judge to any conflict, in effect becoming a State. This small change had disastrous consequences. The king could then tax private property, instead of having to ask property owners for subsidies. He could now also legislate. As a result, law enforcement gradually became more expensive - its quality dropped as there was no competition in its application and its price rose, as it was financed by a compulsory tax.

The establishment of absolute, and then constitutional monarchies also brought about a new level of violence as the monarch could now externalize the cost of aggression onto third parties - tax payers and draftees. This in turn fueled the desires for imperialism - territorial conquest through war and terror.

How did the king manage to achieve this transition? Did he not face resistance from the other nobles and aristocrats? He did so by corrupting the public sense of justice sufficiently enough to crush the resistance:

- He appealed to the "common man" by offering them freedom from their contractual obligations with respect to their lords.

- He appealed to the aristocracy by offering them places at the newly expanded royal courts.

- He offered the intellectuals secure positions as advisors and trustees. In return they started to portray the history before the arrival of the absolutist king as lawless anarchy, with one man being another man's wolf, and they started to portray the transition to ultimate judgeship as a contractual agreement between rulers and ruled.

Things eventually became worse with the transition to constitutional monarchies as the constitution actually codified and formalized the tyranny of the monarch. It did not protect the people from the king. It protected the king from the people. Even the lingering suspicion of whether the ability to tax and legislate is just, was slowly but surely dispelled.

What brought the king's demise was a call to the same elements that elevated him - egalitarian sentiments promising the common man an improved social position compared to his betters. The king's promises of better justice turned out to be empty. Likewise, the exclusion of other nobles as judges angered them, prompting them to turn their backs on the king. The criticism however, was misguided: instead of targeting the ultimate monopoly of law-making, intellectuals, nobles, and commoners were infuriated that the elitist king stood above the law. Their solution was a democracy, where nobody would be denied entry into the State apparatus and this would uphold the equality of all before the law.

But this was an absurd proposition. The democratic equality where everyone is equal in terms of entry to the government is completely different from a universal law, applicable to everyone. In a democracy, while no personal privilege exists, functional privileges exist. State officials are privileged in that they're protected by public law, while those outside of the state by private law. The simple distinction between public and private law is a manifestation of those privileges.

Public officials are allowed to finance their spendings through taxation. They are permitted to live off of the property of those outside of the state. And by opening this privilege to all, everyone can live off of theft by simply becoming a public official. The distinction between robbers and robbed also becomes blurry, and if you don't know who you're staling from, you're more likely to steal.

The parliament can legislate and create new laws that favour the representative groups that propose and vote them into effect. They are not bound by any superior natural law (even constitutional law).

The transition from a monarchy to a democracy is essentially the replacement of an "owner" with a temporary "caretaker". The owner is the monarch whose lineage owns the country. As a result, the king is relatively future oriented and has low time preference, thus seeking to maximize the long-term present value of the country. That makes him more likely to invest in long-term capital building activities. Whereas the caretaker - the current ruling party, or even the current individuals in charge - have a fixed term in which they own the country, therefore have an incentive to maximize their wealth in the short term. This typically involves consumption activities leading to reduction of capital and large scale borrowing at the expense of future generations.

When it comes to free entry in State positions, the democratic case is even worse than the monarchic one because it creates competition for "bads". When government officials can live off of theft, this incentivizes people to become government officials, creating competition for theft and property expropriation. Competition for goods is beneficial but competition for bads is abhorrent, to say the least. Democracy incentivizes that only dangerous men rise to the top of state government.

Under democracy people get more politicized. They are incentivized to participate in the mass confiscation of property where nothing and no demand is off limits. The State becomes the great fiction by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else.

The wealth transfers that occur are increasing in value and intensity. Since those who produce desired goods of higher quality and quantity are typically richer, any unwanted redistribution from the rich to the poor that is not based on voluntary charity, increases the incentives for both economic groups to produce less. Why should the rich bother if they property is taken away? And why should the poor ever be motivated to stay anything but poor? These incentives also lead to plain and obvious moral decay in people’s understanding of the justice and fairness.

Democratic governance also brings about a new power elite of plutocrats - that subset of the extremely rich that recognize the utility of the State in enriching themselves and furthering their own predatory goals. By directly or indirectly bribing the politicians they can promote laws that favour them and increase the quantity of redistributed wealth going to their own subsidiaries. In a realistic capitalist system, these schemes are considerably more difficult to pull off, because the territorial monopoly of legislation and violence is lacking.

Regarding wars, there is also a stark difference between the monarchic and democratic motivations. A monarch wages war mostly for personal gains over tangible properties. The public view war essentially as the king's own matter. Whereas in a democracy, since allegedly everyone owns the State, wars become a matter of ideology - national glory, liberty, civilization, humanity. Battles tend to become larger and deadlier, countries tend to become more armed. The expansionist desire is stronger as a larger territory mean a greater number of tax victims.

Money is also a central issue. Both monarchic and democratic countries recognize that by controlling the money supply and depreciating the currency, a country can easily produce "worthless" fiat money and use it to buy real non-monetary goods at no cost to itself. In an environment of multiple competing states with multiple inflationary currencies, there is a limit to these negative effects: people will sell more inflationary money and buy less inflationary money. One way to counteract this is if all countries form an inflation cartel and coordinate their depreciation policies. But this is unstable, as any country will have an incentive to deviate from the determined policy.

For the cartel to be stable there needs to be a dominant enforcer and this ties back to imperialism and hegemony. A country with a powerful military can order its vassals to inflate along with its own inflation and accept its currency as global reserve currency. This can lead to monetary world domination even without any war or conquest.

These are the defining characteristics of modern democracies. Essentially all of the negatives above are true regarding our democratic governments. Taxation is increasing, ever more specific laws are introduced directing virtually all aspects of private life, the entire finance industry is governed by nothing less than complete centralized planning.

What is the solution? How can we return to a saner, more reasonable and more natural way of living? Some of Hoppe's proposals are advocating for the right to secession, small federated countries, and decentralization at the level of individual communities. To this I also add, cryptocurrencies based on limited and secure supply, as well as weighted voting in referendums and elections.